See You When We Retire

By Ellen Waterston

A conversation with Jaide Downs, co-owner and operator of fields station in Fields, Oregon.

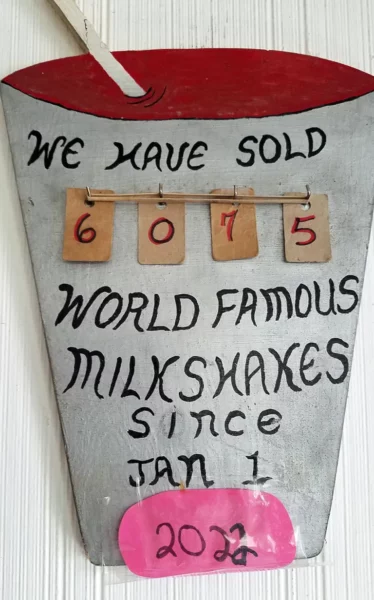

Fields Station is a welcome sight after the five-hour drive from Bend. It’s a chance to get out of the car, stretch, fill up on fuel or buy supplies in the spotless, well-stocked and orderly mercantile. If you plan ahead, you can stay overnight in the snug two-room motel or the adjacent Rock House or Old Hotel. If you’re just passing through, pick up a classy Fields Station souvenir baseball-style cap, enjoy flapjacks or burgers off the griddle, sample one of the famed Fields Station milkshakes. Beer’s on tap, wine by-the-glass and even a liquor store. And there’s something else that, if it could be bottled and sold, would be in high demand: Fields’ recipe for how to make, be, build community.

This post was originally published by the Oregon Desert Land Trust. It is part of their Sharing Common Ground series, all authored and photographed by the talented Ellen Waterston. On Land is partnering to publish these beautiful profiles to a wider audience.

Fields Station was originally one in a string of stagecoach and freight wagon stations established in the late 1800s across the sparsely populated high desert. Their locations were dictated by terrain, yes, but also distance, as horse or mule teams needed a rest stop every fifteen miles (Brothers to Hampton Station on Oregon’s Highway 20), and an overnight layover at a way station every sixty miles (Hampton Station to Burns). Tired horses were revived with feed and water. Fresh teams were ready if necessary. The roadhouses also catered to the travel-weary passengers, offering lodging after many hours of too cold, too hot or too dusty going. Travelers were expected to help push the wagon if it got stuck in snow or mud or get out and walk to lighten the load when the terrain got treacherous.

Most stagecoach stops were owned and operated by pioneer families on land acquired through the Homestead Act of 1862 or its precursor, the Donation Land Act of 1850, both designed to lure white settlers to the Oregon Territory. The entrepreneurs among them established stations, contracting with the stage companies, and getting reimbursed for their services. Charles Fields was one such entrepreneur. In 1881 he built a stagecoach roadhouse on his homestead property that successfully served the route between Winnemucca, Nevada and Burns—that is until stagecoaches were left in the dust by the horseless carriage. After thirty years Charles Fields sold out in 1911.

But as the largest community (everything’s relative) between Denio, Nevada to the south and Frenchglen to the north, and as access became easier thanks to the automobile, subsequent owners had reason to grow the outstation. A Fields post office was established on the site. A gas station was added. The stone roadhouse was converted into a store and restaurant, and adjacent structures into hotel rooms. Houses sprouted up close to Fields Station. Fast forward to 2003 and the school, established by Fields in 1900, had grown to two rooms with two teachers serving kindergarten through eighth grade. The next year, 2004, Tom and Sandra Downs purchased the compound, running it for the next 14 years and adding an RV campground to the mix.

“We’re both so busy. We’re always headed in opposite directions. We joke that we’ll see each other when we retire!”

Jaide Downs

After completing his education and serving in the military Jake, Tom and Sandra’s son, was ready to come home. He knew what it took to operate Fields Station, to live in Oregon’s Outback. But his sweetheart from the flatlands of Nebraska didn’t. Jaide remembers Jake was on pins and needles when he first introduced her to the rugged country he held dear and to his dream of making a life nestled between the Trout Creek and Pueblo mountains. She fondly recalls their long drive cross country together, from the Sand Hills of Nebraska to Oregon’s high desert, and the moment she and Jake crested the hill before the steep drop into Fields: the view of the mountains flanking the massive valley, the seemingly endless horizon. “I fell in love,” she says.

Jaide greeted me at the entrance to the store. She explained that Jake had to go to Burns early that morning to pick up needed supplies. “We’re both so busy. We’re always headed in opposite directions. We joke that we’ll see each other when we retire!” Meanwhile, between raising their son, school activities, community events, plus owning and operating Fields Station, there aren’t enough hours in the day.

With her in-laws and husband as mentors, Jaide proved to be a quick study, equal to the challenges of running the operation. Her efficiency and friendly demeanor belie what it takes to serve up a worth-the-trip cheeseburger with a glass of beer, to fill your car with gas, to have Tylenol on hand to calm that bruised knee, a parking spot for your RV. “We’re really seven different businesses. Each requires a separate permit to operate!” She’s not kidding: Oregon Liquor Commission (off-site liquor license, on-site beer and wine license), Oregon Health Authority (commercial kitchen and restaurant), Oregon Department of Agriculture (foods sold), Oregon Board of Pharmacy (medications), and Oregon Department of Transportation (fuel license).

“There’s a huge need for communities like Fields, for special places like the Alvord Desert, Steens Mountain. We have to preserve and protect them… by education. Then travelers would arrive with an understanding and an attitude of respect. We have to put a wider audience on notice that these communities and this part of the country is so precious.”

Jaide Downs

Thankful every day for her employees, Jaide makes sure to involve them in day-to-day decisions. “I want them to feel they have a say.” And they clearly do if their loyalty and hard work is any indication—from Tiffany, who has worked at the store for nearly seven years and is Jaide’s right hand, to Justin from Tennessee who with his wife and young son stumbled on Fields during a cross country camping trip nearly three years ago and never left. First hired as seasonal help, he now works year-round in the restaurant. His wife’s passion is making cakes to order. Their young son thrives in the Fields school. “We love it here. Love the community. It’s home. Hope to wither and die here,” says Justin with a big smile as he tends the griddle, refreshes my cup of coffee.

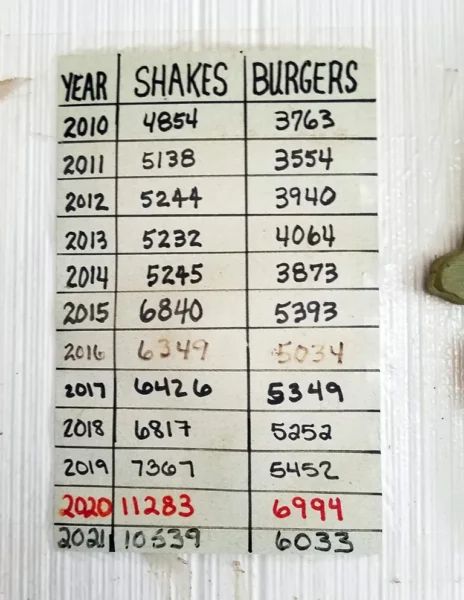

Tacked to one wall of the restaurant is a handwritten tally of milkshake and burger sales. It charts the mouthwatering history of activity over the past two decades and, by association, the growth in numbers of visitors. Jaide points to the only year recorded in bright red letters: 2020. Sales increased exponentially during COVID as people fled the cities and headed for the high desert hills. “It was a zoo for two years,” Jaide says. “Mass chaos. Only now can we take a minute to breathe, to talk to the customers, which is huge.” Some who came were familiar with high desert etiquette, had been to the region before, maybe to hunt, maybe to hike the Pueblo Mountains section of the Oregon Desert Trail, maybe to add to their bird list, maybe just for the quiet, the slower pace. Then there were the newbies, as Jaide calls them. “They had an ‘I-want-it-now’ attitude, weren’t respectful in their treatment of the employees. That’s not how we operate here.” The intermittent cell signal didn’t help. “People without cell service are very nervous people. They didn’t do their research. It showed.” Research would have prepared them for the long, unpopulated stretches between fuel stops, gravel side roads, fickle weather. “And it’s two hours to the nearest hospital,” says Jaide. The newbie response is in sharp contrast to a group of regulars who annually camp in the Fields area, make sure to plan ahead, get the necessary permits, and give back to the community with a generous donation to the school for the acquisition of needed teaching materials.

A dedicated runner, Jaide balances her full workdays by taking time to explore new trails, find new favorites. And too, each evening at 6:00 p.m., when the doors to the store close, “It gets really quiet.” It’s the time this hardworking couple and their son can kick back, sit out on their deck, and watch the weather and light play across the Pueblos. “The view is always special. It’s different every day.” Her hope for Fields in 50 years? It’s clear she has reflected on it. “Keep it the same. There’s a huge need for communities like Fields, for special places like the Alvord Desert, Steens Mountain. We have to preserve and protect them… by education. Then travelers would arrive with an understanding and an attitude of respect. We have to put a wider audience on notice that these communities and this part of the country is so precious.”

Those driving through Fields might wonder who would want to live way out here, what in the world people do this far from everything, how lonely it must be. Truth told, the Fields community (approximately 25 residents living within a mile of the store, and another 100 or so within the 824 square miles served by the Fields post office) is glad that’s the response. The residents of this far-flung area would just as soon it remain a best-kept secret. Meanwhile, they’re hard pressed to keep up with all that’s going on. Here’s a few examples of community (and ingenuity) Fields-style: On the occasion of a recent visit to the school by Portland Opera, the mothers of local students and the Fields Station kitchen produced hundreds of cookies for the singers and musicians, as well as for the vanloads of students who traveled from tiny schools scattered across southeastern Oregon (Adel, Plush, Frenchglen) to hear them. Each Halloween, ranchers host Trick or Trunk in Fields, arriving with treats for the children who come dressed in their princess or superhero costumes. As for the Fields Station, it keeps a generous candy bowl stocked full for kids of all ages during the month of goblins and ghosts. By way of thanks to the community, the Fields Station prepares an annual Fieldsgiving, offering a free meal to anyone who shows up on turkey day. And one more. Students at the Fields School organize all sorts of fundraisers to cover field trip costs from talent shows to field days. Guess who supports those efforts most generously? The small but mighty population of Fields and the nearby ranchers.

The common denominator is everyone. No one sits on their hands in Fields. The fulcrum? Fields Station. This outpost is a reminder that community isn’t something you take, it’s something you give…to a neighbor, a stranger, a mountain, a desert, a creek, a wren, to each other.

The Oregon Desert Land Trust works to conserve private lands in the state’s high desert region. These wild and working lands are critical to ecological, economic and community health. They are based in Bend.

Ellen Waterston is an award-winning writer of both non-fiction and poetry. Her most recent non-fiction book is Walking the High Desert, Encounters with Rural America along the Oregon Desert Trail.