Narratives of Color and Shape: Western Landscape Painter Jill Carver

Jill Carver’s paintings edit the west’s landscapes to dramatic effect. She hopes her work will foster critical dialogue about the future of the West.

Carolyn Quan & Kelly Bennett: Tell us about your journey from Britain to making your home in the American West.

Jill Carver: I’ve been here for 21 years now but I still haven’t lost my accent. I met my husband, who is from Colorado, when I worked at the National Portrait Gallery in London as a research assistant. After we got married, we moved to Austin, Texas, but we often traveled to the Colorado high country to flee the Texas heat. Eventually, our deep love for southwest Colorado and the Four Corners region developed and we ended up choosing Rico as our home. We were drawn by the variety of the landscape here – within a three-hour radius, you can go from mountain forest to high desert, from sage brush country to the red rocks of Moab, and back to turquoise, high-alpine lakes.

KBCQ: What was it that drove your love for southwest Colorado? What was it that drew you into the landscape there?

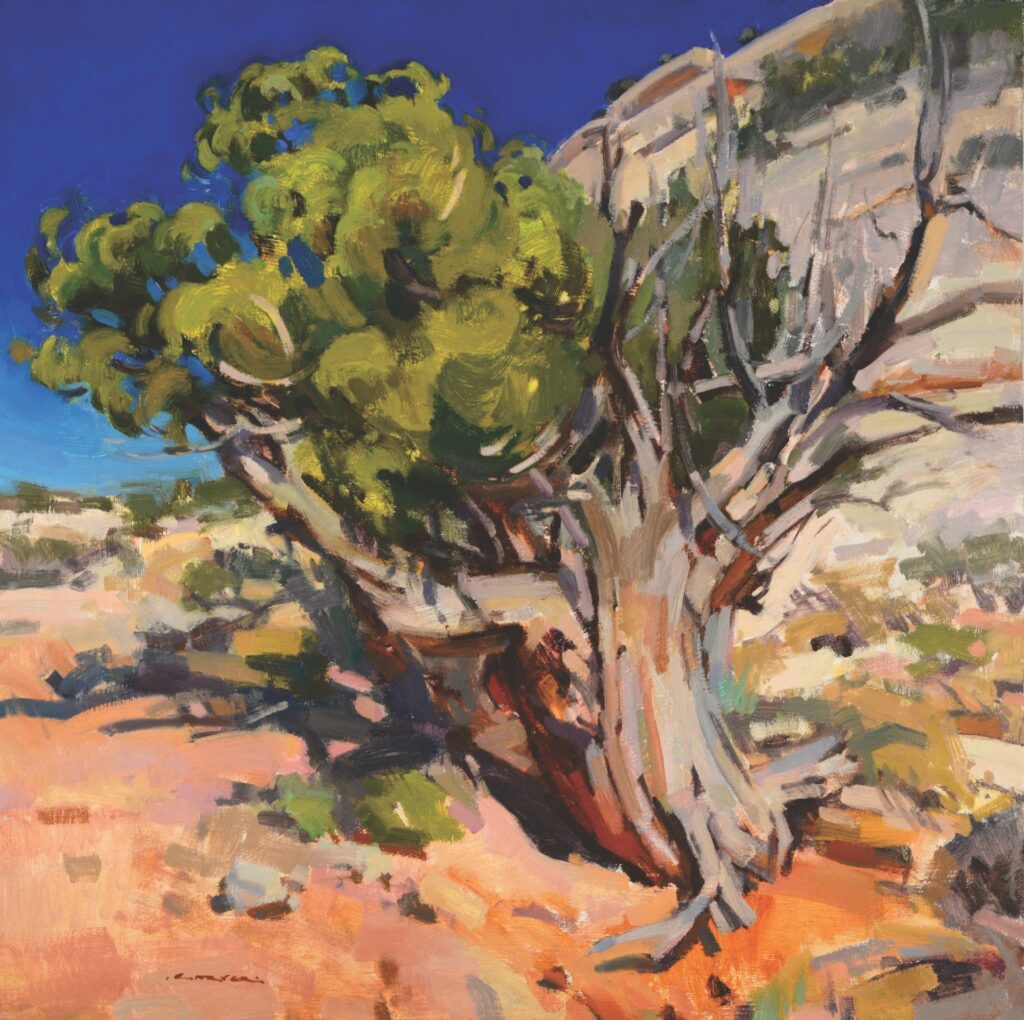

JC: It’s funny how an English person can feel so at home in the Southwest, but there are aspects that resonated deeply with me; I think expanse and scale in particular. I grew up painting and, while a lot of the UK is very pretty and there are ready-made painting scenes everywhere, there isn’t a lot of wilderness. As a kid, I would go on camping painting trips and seek out wilderness areas in faraway places like Scotland. Then I came to the American Southwest and experienced real scale. My first experience in the desert was in Big Bend, Texas, and it felt like I was heading to Mars. The further out I went, the terrain got more sparse: less ‘stuff’, fewer flora and fauna, the greater the expanse and the deeper the quiet. It replicated the most important elements of the experiences I loved growing up in the UK, but in a very different location.

KBCQ: How wonderful to discover your passion for painting so young and pursue it your whole life. Can you share a little more about your artistic background?

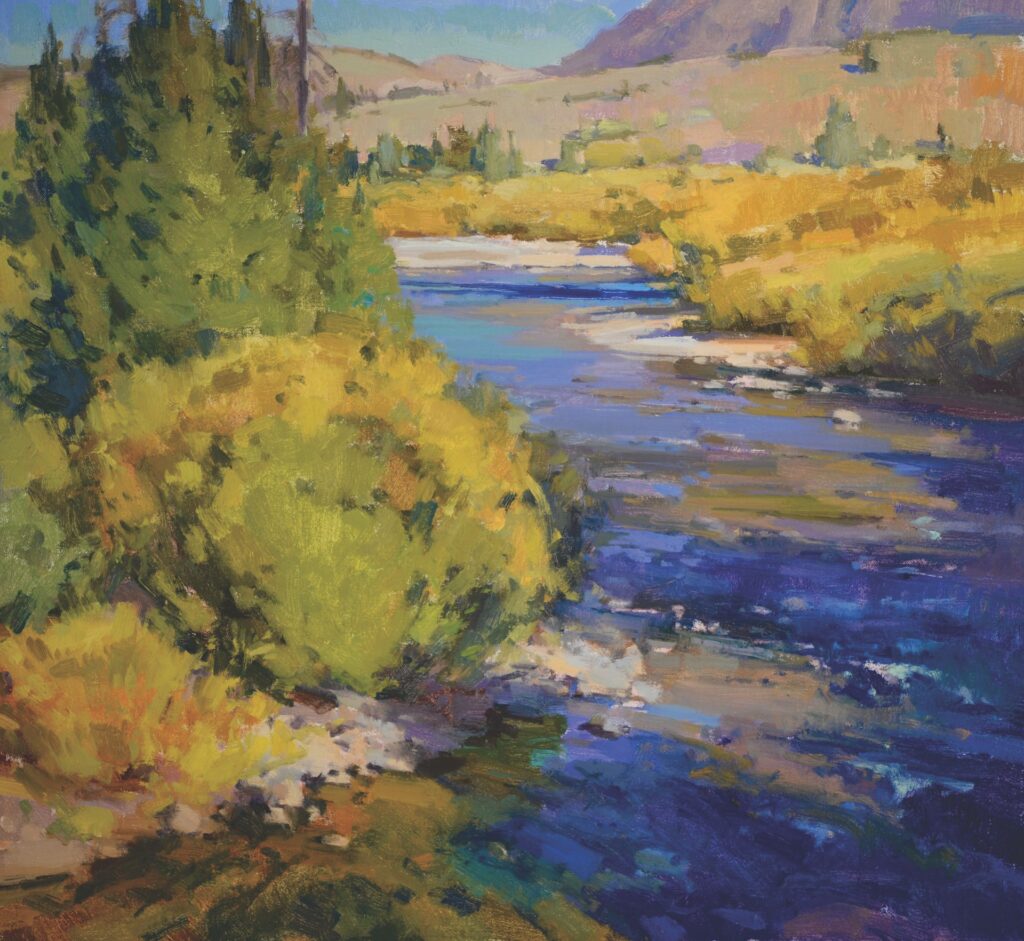

JC: I’ve painted since I was a little kid but didn’t take formal education until I came to the U.S. Painting was always my go-to. I was very shy and way more comfortable in the landscape talking to trees rather than to people. Skip Whitcomb was a very influential teacher and mentor for me as I pursued a more formal education and we maintain an ongoing dialogue now. Many painters’ intent is to recreate a landscape for the viewer, to replicate the experience of walking through the foreground, to the middle ground, to the distant mountains. I like to take a different approach, using elements of modernism that might feel a bit more abstracted and edited down. It allows me to simplify things to draw out the essence of what I’m trying to say about a place. You leave something for the viewer to engage with and complete the thought on their own.

KBCQ: Let’s talk about your artistic style. There is a lot of geometry in your paintings. Can you share with us some perspective from your artist’s eye? It seems like there are principles that translate to anyone who finds themself stopping to take in the view of a beautiful landscape.

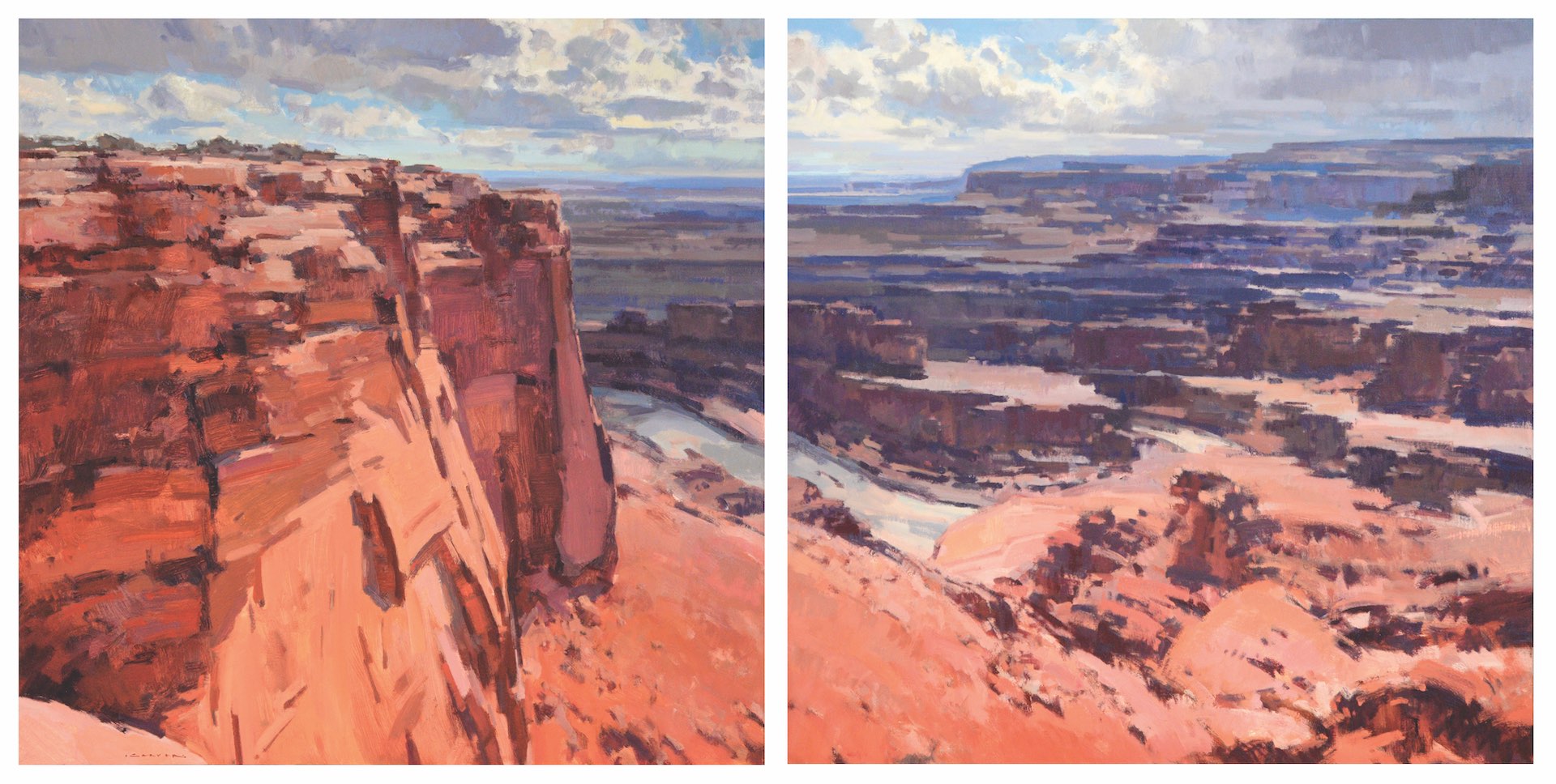

JC: I love complexity, making order out of seeming chaos and finding patterns in things. I love asking questions about what ties a lot of disparate ingredients together. In school, I was very 50-50 in terms of left brain – right brain and was always very mathematical and analytical. It influences my art and how I look at landscapes because I love to examine dynamic symmetry, underlying structure. I seek out those elements. For example, I’m starting work on a picture of the Grand Canyon, which I held off seeing for 20 years, and I’m really enjoying the complexity of the geological layers and the sunlight and shadow patterns that are imposed upon them.

I love complexity, making order out of seeming chaos and finding patterns in things. I love asking questions about what ties a lot of disparate ingredients together.

Jill Carver

I think as humans, we all have different sensibilities, which I encourage my students to explore. Some of us are naturally tonalists, who may see an infinite variety of tonal or value shifts. I personally respond most to shapes and colors. As a result, you will see creeks and rivers, geological light and shadow patterns, throughout my work.

We all see the world around us and impose a cohesive narrative on what we see, in terms of finding a pattern or a rhythm that unites and helps us make sense of it. I encourage my students to think of unity and variety when contemplating this narrative. What elements on the landscape tie it together and create unity in what we see? Is it a color or a shape? Or interconnecting shapes like aspen trees against the sky? Then you ask, ‘where is the variety?’. Nature imposes as much variety as you could ever wish for, and if you include too much into a painting, it can feel busy and chaotic. You have to choose the elements from nature that you want to celebrate. Put it all together into your own narrative and you build a beautiful balance of elements that provide both unity and variety within the piece.

KBCQ: We have talked a lot about patterns in nature. How does human impact on the landscape factor into your art and the way you look at the West?

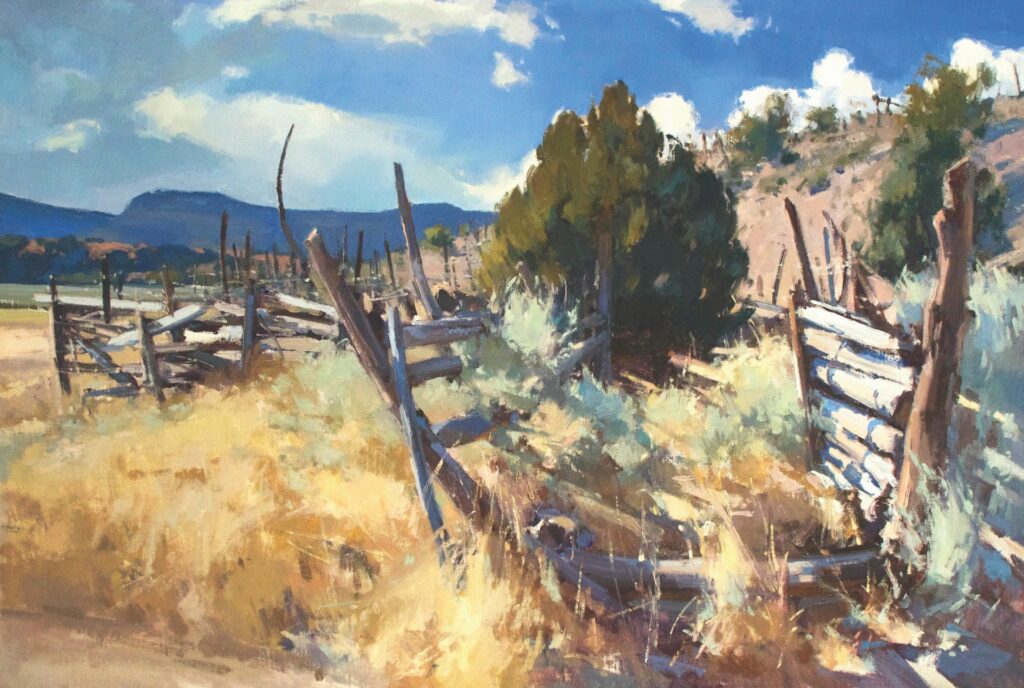

JC: When I started painting, I lived in London and painting was literally a way of escaping human activity and the city. It was a way of exhaling and enjoying quiet away from the realities of people. As I’ve matured, my mentality has changed. When I return to England now and go to places like the Peak District National Park, I realize that is a landscape that has been sculpted, tweaked, farmed, and quarried by humans for hundreds of years. Human impact has truly shaped the land. Where I live now in southwest Colorado, there are certainly aspects that have never been touched, but there are also so many signs of human impact. There was tremendous mining and a sulfuric acid factory here in the mid-century, and while nature seems to be taking back over, the signs still remain. I’m still evolving with respect to how I ‘see’ human impact on these landscapes. Sometimes I realize that I very much enjoy the shape of things that humans have made amongst the shapes found in nature. That makes it sound a superficial enjoyment, but they can be beautiful together.

KBCQ: What do you think about when you see how the landscapes of the West are changing? How do those changes come through in your art?

JC: Art in the West is a genre that has one of the deepest mythical weights to it. I used to have all kinds of conversations with myself about how I reconcile myself as an artist from Britain being in this landscape that has such a huge tradition behind it, and still maintain my own authenticity. In Texas, I remember early trips out to a lot of these deserted, down-and-out Western towns. I didn’t want to paint cliches and I was taking all these pictures of derelict buildings and even got run out of town once. I remember once thinking I was looking at a classic, old adobe building, the epitome of old West Texas. In reality, when I got up close, it was effectively fake – just decaying two-by-fours, chicken wire, and concrete.

It highlights an ongoing dialogue among many people living in the West, whether in overt conversation or subconsciously: what is authentic and what’s myth? How does our mythical understanding of the West reconcile with what is, or was, authentic? In today’s West, we get to use our own sensibilities to see beauty in an authentic way. For example, rather than painting the quintessential Texas blue bonnets, I was more drawn to pictures of scrub landscapes full of prickly things and intimate creeks contrasting beautiful limestone. All places change over time; it can be useful to identify how our own mythological views of a place shape the ways we consider that change.

KBCQ: How about when you came to the mountain West? What was that experience like where working lands are so woven into wild places?

JC: That is certainly the case here in Rico, where our mining history is very evident. We have a population of just 236, but in the height of the mining era, it was 5,000. A lot of us get twitchy about another 50 homes being built, but then we must remind ourselves that this landscape used to be home to many more people. There is a constant ebb and flow. After decades of damage from mining, nature has been restoring itself for 60 years. Now, with major population growth, it is tipping back in the other direction where we will start seeing an impact on the forests and water systems. The critical conversations about the future of these places are ongoing. For example, we are sitting on a massive molybdenum reserve and many people are worried about it being developed. Then you think about the changing West and realize that you have to ask: is a well-run mine better or worse than a Crested Butte-style ski resort, or a hot springs resort like Ouray and a town entirely reliant on a tourist industry?

It is such a critical time to put our heads together and talk about these landscapes. I’m happy that the conversation about conservation is broader and more inclusive than it ever has been. I think the idea of sustainability is sometimes defined quite narrowly and that, as humans, we often don’t see ourselves within an ecosystem. Rather, we ask, ‘how can we sustain what we want to do, how we want to entertain ourselves? sustainably?’ It’s a much broader conversation than that.

KBCQ: How does art facilitate this conversation?

I think the very basic function of art as a landscape painter is to celebrate a landscape that everybody loves. Everyone, whether they are a hiker, mountain biker, hunter, miner, rancher, or banker, has a visual relationship with the landscape on some level. It may be from memory; it may be through a romanticized vision. Art is a means to tap into a common view shared by most people: that these places are to be revered and celebrated. I think that most people have a very positive relationship with beautiful landscapes and understand the need to protect and preserve them. People appreciate these places, even if they can’t access them or use them to their advantage.

Art is a means to tap into a common view shared by most people: that these places are to be revered and celebrated.

Jill Carver

People, particularly the younger generation, are less into commodities and goods and more inspired by experiences. I do a lot of plein air painting and I find that people love when I share that part of a painting’s story is an experience in nature. It can make art relatable and the landscapes revered on an even deeper level.