The Ghost of the Prairie

Finding an endangered species on his ranch scared the daylights out of Russell Davis. What he did next may have saved his town.

It’s before dawn, and a group of bird watchers, scientists and ranchers get on an idling school bus. No, this isn’t the start to a bad dad joke. It’s sunrise on the high plains of eastern Colorado, and this is the first day of the Mountain Plover Festival—an event celebrating an elusive little bird, a species so hard to find that it’s been nicknamed the “ghost of the prairie.” Though the bird is the central focus of the festival, attendees often discover much more than plovers.

The event, hosted by the Karval Community Alliance, takes place over a long weekend every April, when mountain plovers migrate to the shortgrass prairie and fallow crop fields to nest. The festival was launched in 2009 to help generate economic activity in the community.

Dan Merewether, a local rancher and president of the community alliance, says people come for more than just the birds. “Two percent of people live on the land now as ranchers or farmers. So, a lot of people, even in the small towns, they don’t really have that connection anymore to farming or ranching or the land. I think a lot of these people really appreciate being out in the country and being part of this lifestyle, seeing the animals.”

Karval is a small unincorporated community on Colorado’s high plains. Residents joke about their home being “50 miles from anywhere.” There is no grocery store and no gas station, but there is a K-12 public school. And there’s the Karval Community Center, a simple building clad in white vinyl that serves as the base of operations for the festival. The school cook, along with the local women’s clubs, prepare sthe meals for festival-goers. One lunch featured generations of mismatched crock pots lined up serving refried beans, rice and ground beef for a taco bar.

Plovers discovered

After rumbling several miles from town, the bus pulls off the gravel road to a green ranch gate. Someone hops out to open the gate, and the bus rolls through. This is the first stop of the day: Wineinger-Davis Ranch, where the story of the mountain plover in this community began.

One summer morning over 20 years ago, Russell Davis, of Wineinger-Davis Ranch, stepped outside and saw something strange on one of his pastures: a Toyota. “If you know anything about our cow country in eastern Colorado, you don’t see too many Toyota pickups,” he chuckled.

Before long, Davis was standing in the middle of a prairie dog town shaking hands with a young researcher wearing khaki shorts and a fisherman’s cap, with a pair of binoculars around her neck. “She was really excited,” said Davis.

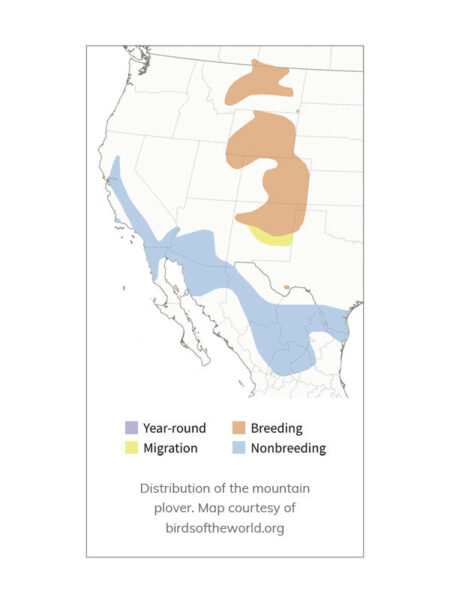

Despite their name, mountain plovers (Charadrius montanus) are a grassland bird endemic to the Western Great Plains. Unlike other plover species, mountain plovers usually don’t live near water, preferring to nest in short grass or bare ground like the prairie dog towns and farm fields in eastern Colorado.

Standing in his pasture, Davis learned two things that day. He learned he had mountain plovers all over his ranch. And he learned that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) was considering listing the bird under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

“The air went out of my lungs,” he said. “I was pretty upset.”

A real education

Because most mountain plover habitat is on private lands, scientists and officials needed landowner buy-in to conduct the research that would determine whether or not to list the bird under the ESA. According to the USFWS, 84% of the central grasslands in the United States are privately owned, making voluntary collaboration with ranchers and farmers critical to successful conservation.

Initially, Davis was deeply concerned about the plover and the threats that regulations to protect the bird posed to his operation, a feeling relatable to many landowners. But after some reflection, phone calls and honest kitchen table conversations, Davis decided to welcome partners and researchers to his ranch to understand how the plovers were doing. After all, if the birds were on his operation, then he must be doing something right.

“I began to realize that I’m not only a steward of cattle and the landscape, but wildlife too. That was a real education,” said Davis.

As Davis began doing work with outside partners and publicly touting his plovers-in-residence, his neighbors made him a pariah. People even stopped inviting him to help at brandings, Davis said. But after many years and many more kitchen table conversations, the community finally rallied around the bird. The Mountain Plover Festival is a celebration of this turnaround and an open recognition that what’s good for the bird is good for the rancher. There aren’t many towns 50 miles from anywhere that welcome outsiders to the area to watch for birds and other wildlife on private lands, eat home-cooked meals, and make new friends from all walks of life. For many attendees, the most memorable moments of the festival don’t happen behind binoculars, but over tacos.

“The fact that you get to meet the ranchers and talk to ’em and ask them about their cows…and they’re explaining what’s happened here in the past and the old homesteads…that’s what I enjoy more than the birds,” said Carol, who has been making the trip from western Colorado to the festival for three years now.

And the question of ESA listing? In 2011, in part because ranchers like Russell Davis welcomed researchers onto their operations, the USFWS determined that “the mountain plover is not threatened or endangered throughout all or a significant portion of its range.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Jackie Standiford

Very good! I enjoyed your article.

Aunt Jackie.

Jackie Standiford

Great! Proud of you Zack!

Dawn Welsch

Great writing!