WESTERN ART AFICIONADOS AND MOTHER-AND-SON TEAM CAROLYN QUAN AND KELLY BENNETT, SAT DOWN WITH DINÉ ARTIST TONY ABEYTA TO DISCUSS HUMAN CONNECTION TO THE SOURCE AND POWER OF ART TO TELL STORIES.

Tony Abeyta

Maxwell Alexander Gallery

Photo by Beau Alexander

ART IMAGES COURTESY OWINGS GALLERY, SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

KBCQ: Take us back to your childhood and growing up in Gallup and a family of artisans.

TA: I grew up in Gallup on the Arizona–New Mexico border. The early, seminal relationship I have with the land comes from my hometown. We were a creative family. My mother did ceramics and beading, my sisters were into ceramics, and my father was a renowned traditional Indian painter at the time from the Santa Fe Indian School of the1930s and ’40s. I would say that art was natural for me in my life. We were pretty developed in our understanding of art, especially in a small town. As a 10- or 12-year old, I understood concepts about Flemish and Italian Renaissance painting and I knew who painters like Grant Wood were. It was an advantage—my mother collected books, so I grew up with art and anthropological references all around the house. My father had a daytime job, but on weekends he painted and had collectors come in from all over.

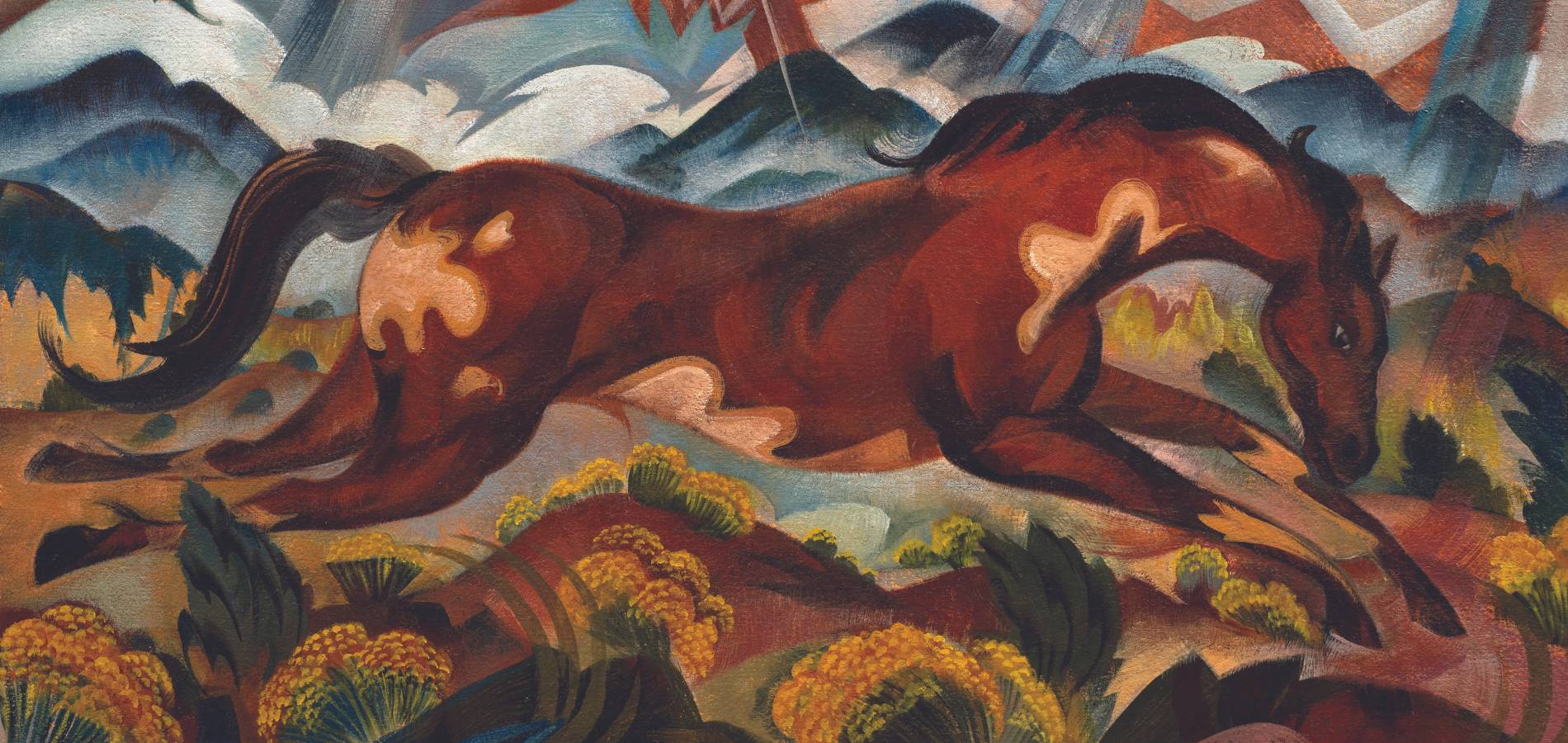

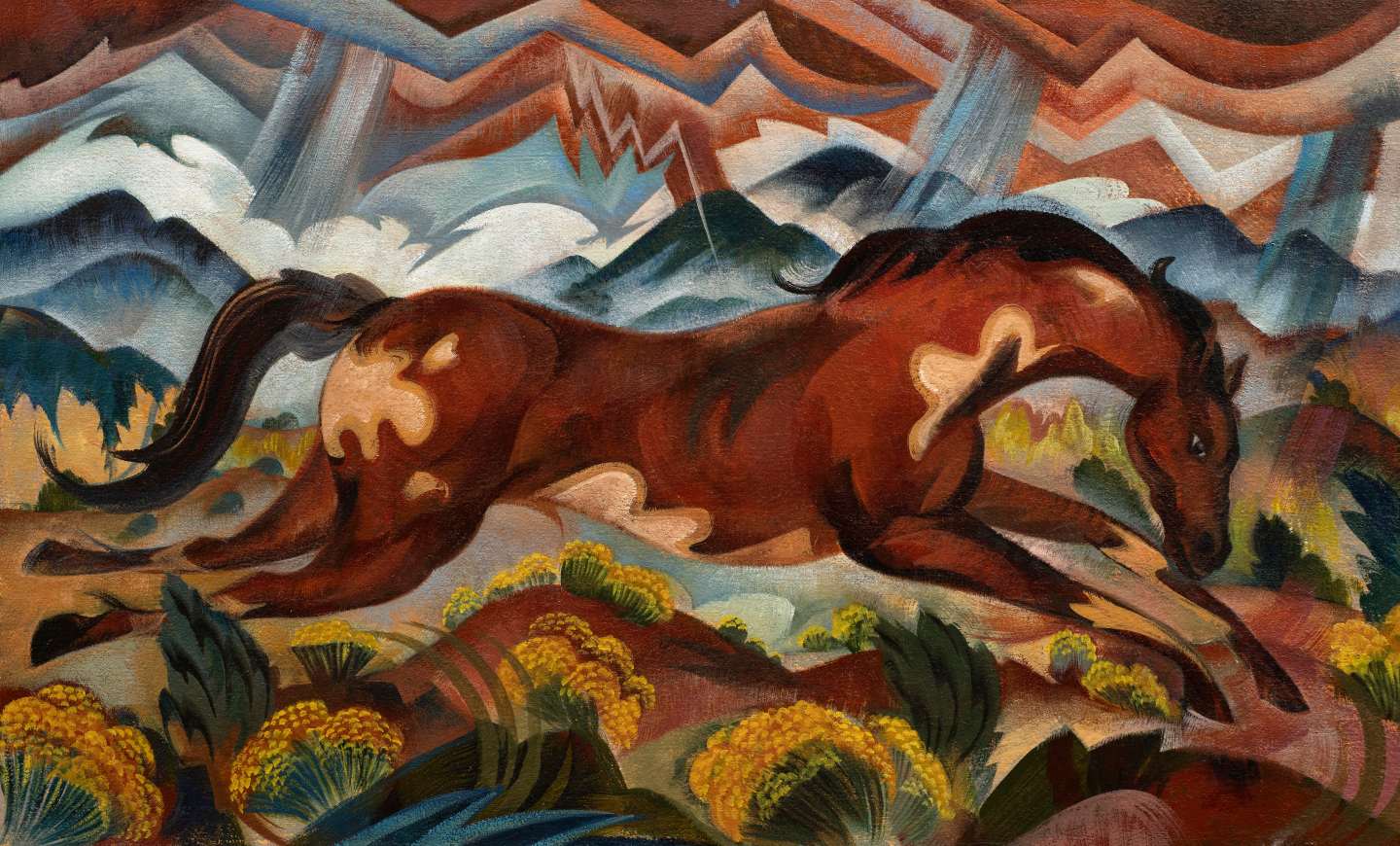

THE RUNAWAY, D. 2021

oil on canvas

20 x 40 inches

KBCQ: So painting was not your father’s profession? Narciso Abeyta was and remains a renowned Native American artist. What was the landscape for Indian art at the time?

TA: Back in the ’70s, you could make a living off painting, but for American Indian art it was a smaller collector base and there was not a lot of financial support for many of those artists. He worked for the State of New Mexico for the employment agency as an interpreter for people who spoke Navajo on the reservation and helped place them in work opportunities.

KBCQ: Growing up in such a culturally rich, art-driven setting, did you see the path for yourself in art right away?

TA: I grew up surrounded by it and did some creative stuff, but I wasn’t immediately drawn to art and I didn’t see myself growing up to be an artist.I was a builder – art didn’t seem like a responsible pursuit or one that would allow me to pay my tuition and bills as an adult. I built club houses and I wanted to be an architect, but I was really bad at math.

Art found me later, by accident. I was working as a movie theater projectionist and realized that the job had its limitations and no real upward mobility. Add to that some wanderlust and with the encouragement of my older sister, Elizabeth, who went to school there, I decided to go to the Institute of American Indian Art. I wasn’t that good, but I got in and experimented with drawing, painting and photography. I found myself staying late in the painting studio, sometimes into the early morning. That seemed like a good sign that I found something that I was passionate about. The passion lets you be and do what you love.

Black Mesa, D. 2018

oil on canvas

60 x 50 inches

KBCQ: Your academic pursuits took you far from small Gallup and Santa Fe. Why leave the Southwest and how did your time on the East Coast shape your art?

TA: I really wanted to get to the East Coast and ended up going to the Maryland Institute of Art, which was an academic school. I had to get back to that math, but also learned a lot about line drawing, color theory, composition – all the necessary things that artists should be engaged in. I had family close by and could take the train to see art. I learned a lot going to the National Gallery of Art, Hirshhorn, New York City. I saw the Anselm Kiefer show when it first came and got to see the German abstract expressionists. I learned a lot seeing those contemporary exhibitions and being exposed to post modernism and minimalism. As a student of art, I devoured it and it was a catalyst for not only the way I think and appreciate art but a long-term love of learning. It became part of my job description and how I assess my here and now as an artist. Art has taken me a lot of amazing places around the world where I get to keep learning. All of the places – New York, Chicago, the south of France, Florence and many others – art took me on an amazing journey of discovering things and understanding what creative people around the world are doing. It had a strong effect on me.

WINTER, D. 2021

oil on canvas

30 x 40 inches

KBCQ: Speaking of the here and now, you returned to New Mexico.

TA: For what I’m working on now today and engaged in as an artist, Gallup has all the resources I need: landscape, sky, cultural values, connection to Source. Gallup serves as a foundation and the basis for where I come from and what happens next.

KBCQ: You spent a lot of time away from Native American art and experiencing many different styles and approaches. Did your roots constantly permeate your style as it developed or did you find your back to them?

TA: I found my way back. Roots are a part of it, but you have to cultivate ideas and skills, accept some influences. The art history of the world is hundreds of years of artists who problem-solved. They learned how to see and paint something, the benefits of certain paint types, how to understand spatial and atmospheric perspective and guiding the eye through a painting. Bearing witness to great art and artists was important to my journey, whether I was conscious of it or not.

KBCQ: You’ve spoken a lot about connection to Source. Can you explain what you mean by this?

TA: I believe that we have a connection, very much like an umbilical cord, to vernacular. The places that we come from, the culture, the people. If you live in Chicago but you are from rural Iowa and your Source is really farming, then you are going to have a deep connection to the land, planting, seasons, solstice. It could make sense that you become a painter like Grant Wood or Thomas Hart Benton and you are able to draw from everything that is part of your childhood. The people, the humility of those places, for example.

The Source for me is about cultural connection to land, to mythology. For example, certain rock formations on the Navajo Reservation are part of our creation story. Ship Rock and SpiderRock and lava flows – lava flows are the blood of giants that walked the earth in our mythology – that all has a narrative of its own. With that back story, the land itself as we see it has its own story. You have to think about the billions of years it has been here, numerous mass extinctions, and that is before people. Once we add people, each Native American tribe has its own creation myth for how they emerged. Some people emerged from a lake, some from an underground mountain, others through a hollow reed from an ant pile. The land has a story of its own and people have a connection with those places [they originate from].

KBCQ: How does a person’s Source affect how they see the world?

TA: It’s powerful connection to your origin. The Native Americans that grew up on the Rio Grande are directly connected to that river. Navajos have a connection with four sacred mountains and those create the perimeter of that Navajos world. The Pueblo world almost exclusively follows along a snakelike river and that is tied to migration. You see that when we talk about Source, there is such an amazing amount of response. Your connection to where you come from can be so specific. Even people who come from New York, they have a very clear understanding of what it means to be from there –they even have bumper stickers to announce, “I love NYC!”

KBCQ: Let’s talk about that, connecting art and Source. How does it flow into your artistic vernacular?

TA: I come from the middle, the epicenter of Navajo land, and this shapes my perspective. If I’m painting landscape, I am painting the connection between sky and earth, seasons, how light penetrates the landscapes. I’m thinking about herbs and plants—the relationship that birds and other animals have to them. Beyond that, I’m painting monolithic rock formations, understanding the backstory and what it means culturally. I look for the rhythm in the landscape because that’s something that can be poetic and subtle or powerful and foreboding, like a thundercloud. That’s part of the landscape and my narrative.

WINDOW ROCK, D. 2022

oil on canvas

50 x 60 inches

KBCQ: How do these landscapes inform what you choose as subject matter and how you paint it? What are you hoping to communicate?

TA: The inspiration is always different. Sometimes I look at something and it’s really simple but so inspiring. The landscapes in their own way are emotional and affect the way that we feel, so I get to paint a depiction that shows how I feel. That creates a new dialogue with me, the landscape and the viewer. How do I capture this feeling of space, of depth? I question how the subject and my painting make me feel; it should feel like an amazing experience that I am capturing.

KBCQ: Many of your landscape paintings that include a human element depict very profound relationships between people and the land. How do people, the Source, the landscapes converge in these images? How do the pressures of development, changing land use and change flow into your art?

TA: The connections people have to land, these define their sacred spaces. All of those paintings are references of people occupying those sacred spaces. They are not paintings about colonialism or change; they are to show the sacred, intended purpose of that landscape.

I look at what I do and think, “Is it always going to be like this, always and forever?” I tend to think maybe not. I have watched a lot of change, and sometimes the changes are abrupt. Maybe my art is documenting the world I see in the here and now, knowing it is going to change. A place could be developed or climate change may make it less fertile or even more tropical. To be conscious of the land around us is to know it will change. I get to paint something and maybe in, say,50 years, someone will get to look at it and see something that doesn’t exist anymore. Maybe in 100 years it will look the same. My paintings will share the land as I knew it, a representation of my Source.

COYOTE, NEW MEXICO, D. 2021

oil on canvas

20 x 26 inches