With over 300 million acres set to change hands, conservation professionals are helping farmers and ranchers work through the succession planning process.

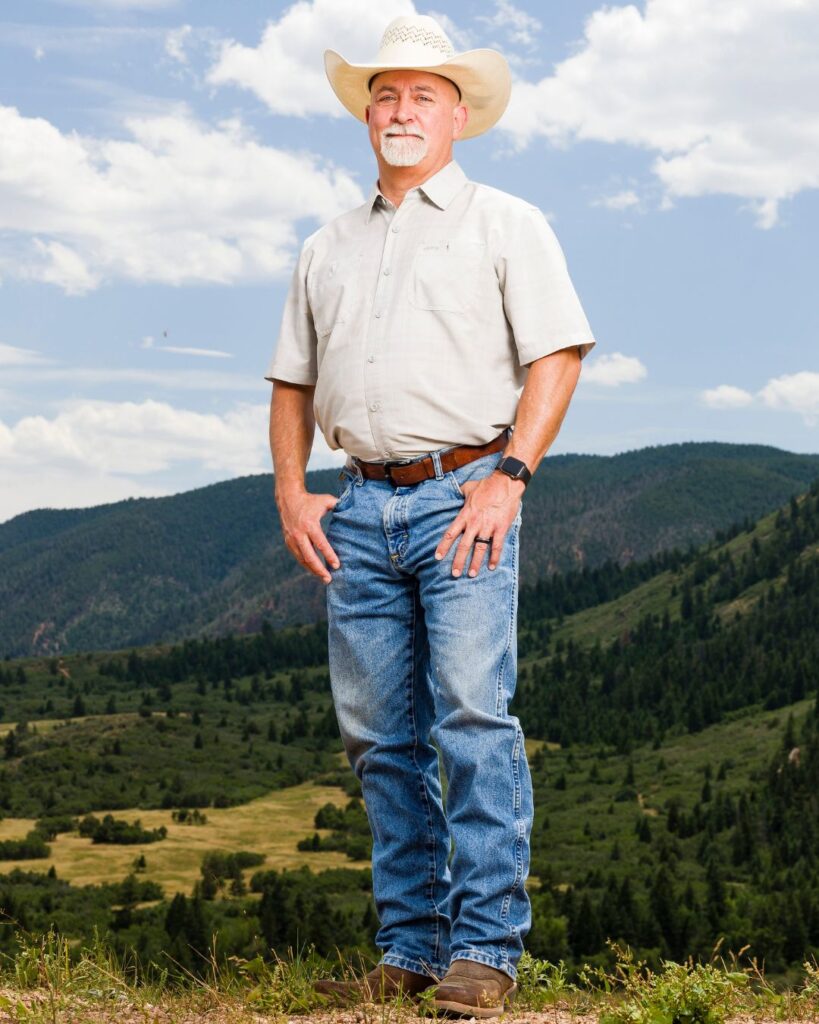

Dan Skeeters grabs his folder and notepad, shuts the car door, and flashes a soft smile. He walks across the driveway, jaw-dropping Colorado ranching landscapes fanning out in every direction, and knocks on the front door of a brick home. Before stepping inside, he removes his cowboy hat and offers to kick off his boots.

Joe and Kay, an older couple who have been ranching this land for decades, welcome Dan inside. They walk together down the hall and to the kitchen, where they each pull up a chair around the circular table. The conversation drifts from the weather—it’s 99 degrees, a sweltering early August day—to hunting to family history. Then, with a question from Dan, it takes a more serious turn. Opening his folder, he asks: “Do you have a succession plan in place for your ranch?”

Dan’s question is a good one, and it’s something that more farming and ranching families across the country are, or should be, considering.

Research from American Farmland Trust suggests that about 30 percent of the country’s agricultural land—more than 300 million acres—will change hands in the next two decades as aging farmers retire or, candidly, die.

How that land transfers, and to whom it transfers, matters.

This acreage could shift to young, aspiring farmers in the next generation. That’s the logical next step for an agricultural property. The current owners step away; they pass their land down to an heir interested in farming or sell it to a non-family member looking to get started; the land remains in agriculture and the new farmers thrive, producing food and fiber into the future.

That process sounds simple, but it usually isn’t. For a variety of reasons, transitioning a farm from one generation to the next is complex.

Economic factors make the process especially difficult. In many areas, land prices are through the roof, making it tough for young farmers to purchase acreage. But because retirement costs are also high, many aging farmers can’t afford to sell their land at a discount, even if they want the land to go to a next-generation farmer. For decades, they have invested their financial resources into paying for the land rather than putting funds into savings or retirement accounts. They need to extract that equity to pay for their next phase of life or cover end-of-life healthcare.

Economics aside, emotions also complicate the farm and ranch transfer process. For one, it’s difficult for many farmers to imagine stepping away from agriculture. It’s all they have ever known. It’s a livelihood and a lifestyle, and many aging farmers say they want to die caring for their land. That sentiment is admirable, even inspiring—and it also creates complications for ensuring the land’s legacy can live on.

For heirs, emotional questions about “fairness” can arise. Imagine a family with three kids. One wants to take over the farm or ranch. The other two have no interest in agriculture.

Should the farm be left to the interested heir? Maybe—but that could shortchange the others or make them feel overlooked.

Should the land be split into equal thirds? Perhaps—but that division could make the individual parcels less viable for farming, especially if the one heir that wants to farm can’t afford to buy their siblings out because, again, land prices are absurdly high.

No matter the answer, simply asking these questions can create conflicts that families would rather avoid. But avoidance is a bad long-term strategy.

To top it all off, families must deal with legal complexities. Because succession and estate planning can be expensive, families sometimes struggle to cover those costs or put off the work—meaning that the current owners of a farm may die without a legally valid will. When that happens, farmland can become “heirs property,” a tenancy-in-common arrangement that can leave families vulnerable to dispossession of their most valuable asset.

Throw in tax dynamics and housing questions, and you jumble the process even more.

All these factors make the transfer of land between generations difficult—and can tempt many families with exasperation.

As such, at these moments of generational transition, more and more agricultural land is being subsumed into large farms that, according to data from the Census of Agriculture, have expanded dramatically in recent years. Or the land is being bought up by non-farming investors, like private equity firms and asset managers. Or it’s converted to real estate development like subdivisions, strip malls, and warehouses, an outcome that’s especially affecting rural communities within an easy drive of urban areas. These outcomes create uncertainties for the future of our farming and food systems. That’s why Dan Skeeters’ work is important.

“I was coming across landowners who didn’t have a plan for the future. I mean, I was shocked by the number of people who didn’t have a will, who didn’t have a long-term care policy or a trust set up to protect their assets. And slowly, I started to realize, ‘Wow, this is a problem.’”

– Dan Skeeters

Dan works with Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting agricultural landscapes. Using a legal tool called a conservation easement and working in partnership with farmers and ranchers, the organization ensures that land will always be available for raising crops and livestock. These land conservation efforts are crucial.

Yet organizations like CCALT—and their staff members, like Dan—are also recognizing the importance of helping families with succession planning, even if such work hasn’t traditionally fallen within the land conservation sphere.

“In my work,” Dan says during a one-on-one interview at his own kitchen table outside Denver, “I was coming across landowners who didn’t have a plan for the future. I mean, I was shocked by the number of people who didn’t have a will, who didn’t have a long-term care policy or a trust set up to protect their assets. And slowly, I started to realize, ‘Wow, this is a problem.’”

Other conservation professionals were noticing the same thing. Alongside three dozen different organizations across the country, CCALT has joined the national Land Transfer Navigators project, led in partnership by American Farmland Trust with support from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

As CCALT’s lead “Navigator,” Dan hosts succession planning workshops for farmers and ranchers. At these events, he typically invites a panel of experts who can speak about different aspects of the farm transfer process. Experts aside, Dan also asks a family to share their succession story aloud.

Sometimes, the story is positive, and it serves as inspiration for how others could move forward. Other times, the story is dark, touching on the broken family relationships and lost land that can happen when succession planning is ignored or done poorly. These stories build solidarity among the attendees, putting them in community with fellow farmers and ranchers who can empathize with their challenges and hopes.

“The best, most poignant and moving portions of the workshops we’ve done so far have been the personal stories and journeys of landowners,” Dan shares. “Those are always the highlights of these events. You can tell people what to do and give them the facts, figures, and technicalities, and that helps. But those stories really bring it home.”

“We’ve got two kids,” Joe says, grabbing the handouts, “and I was just talking with Kay about this the other day. We need a plan. We need to come up with something, but I don’t have a clue where to start.”

Dan also conducts one-on-one visits, where he sits down with farmers and ranchers to offer direction and answer questions. Given a prior career in commercial real estate, Dan brings a wealth of transaction experience to these conversations—as well as his own family experiences with land transfer.

His family once owned a farm in rural Kentucky. One fateful day, two businessmen drove up to the farm and asked to speak with Dan’s grandfather. They spoke briefly in the yard and shook hands. Dan’s grandfather had been offered a “no-brainer” deal to sell the farm, an “offer he couldn’t refuse.” Now, a chemical plant covers the land. The money from the sale helped his family, but soon after moving away, Dan’s grandfather spiraled into depression and alcoholism. His identity was tied to being a farmer, and he lost that when the land was sold.

Dan doesn’t resent anyone involved in that deal, though he wishes he could’ve known that place as the productive farm it once was. He just wants farmers and ranchers to know that they do have choices about the future of their land—and that every major decision regarding a farm’s fate is worthy of careful consideration and planning.

In addition to his personal stories and real estate transaction knowledge, Dan also brings lessons learned from trainings offered through the Land Transfer Navigators program. He draws on best practices for navigating conflict, creative approaches to conservation easements, and understandings of heirs property, all gleaned from a series of virtual and in-person trainings.

Yet one of the most important things Dan shares in these one-on-one conversations is humility. “Starting out, I thought that I needed to learn everything there was to know about succession planning and estate planning, all that stuff. I soon realized that it’s impossible for one person to know everything.”

Grabbing his phone, Dan pulls up a picture of him speaking in front of a PowerPoint slide at their last workshop. There’s a quote on the slide. “It’s one of my favorite quotes of all time, and it’s by Will Rogers. ‘Everybody is ignorant, only on different subjects.’”

So instead of trying to be a one-stop shop of succession knowledge for farmers and ranchers, Dan leans into being a convener. When there’s a question he can’t answer, there’s an attorney or tax adviser, an extension agent or accountant who can—and Dan will gladly connect farmers and ranchers with these professionals. “It may sound cliché, but there’s that saying that ‘a small group of committed people can change the world,’” says Erik Glenn, the executive director of Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust. “Dan is the epitome of that. He has taken this role on with such passion, and he is the reason it’s working so well.”

Back at Joe and Kay’s ranch, Dan flips through his folder and pulls out an estate planning guide. He grabs an invitation to an upcoming workshop, too, a four-day deep-dive where families can leave with a ready-to-go plan for the future of their land and farm business. He slides these papers across the table.

“We’ve got two kids,” Joe says, grabbing the handouts, “and I was just talking with Kay about this the other day. We need a plan. We need to come up with something, but I don’t have a clue where to start.”

Dan gives a knowing nod. He’s heard this before. “If there’s any way I can help you,” he says, “I’d be happy to do that. … Think about the best-case scenario. What would you like to see happen?”

Pushing his chair back and reaching for his hat, Dan smiles again. “Let’s start with that vision.”

If you’re a farmer or rancher and would like more information about the Land Transfer Navigators program – or if you’re not a farmer or rancher but are still interested in learning more – visit farmland.org/land-transfer-navigators

Featured photo and photos with text by Michael Ciaglo.