Water, Not Land, Limits Growth in Colorado and the West

A decades-long boom has permanently reshaped Colorado. Along the Front Range, cities from Fort Collins to Colorado Springs have merged into a nearly unbroken wall of development. Yet as the population swells, the most pressing constraint on growth isn’t open land—it’s water.

Municipalities have scrambled to secure supplies for new homes, businesses, and lawns. Increasingly, they’ve looked to agriculture. That trend threatens the future of rural communities, where farms and ranches are the economic and cultural backbone. But new approaches to water management, urban growth, and land use may offer alternatives to the “buy-and-dry” deals that hollow out small towns.

As Colorado’s population swells, the most pressing constraint on growth isn’t open land—it’s water.

Thinking Outside the Pipeline

For many farmers, selling water rights can be the most straightforward path to financial security. The sale provides a nest egg in an era of volatile commodity prices and rising costs. But once water leaves the land, fields go dry, families move away, and rural economies decline.

Colorado Open Lands (COL), a nonprofit land trust, has been working with ranchers in eastern Colorado to shift some of those incentives, focusing on community resiliency in the face of these pressures. COL has been convening water providers, municipalities, and agricultural leaders, to help rural areas negotiate from a position of strength rather than desperation.

“What we’re trying to do is bring water providers to the table and give [rural communities] an option. The Thorntons of the world have dried up a lot of northern Colorado. Aurora is buying water everywhere,” said Carmen Farmer, the senior conservation project manager for Colorado Open Lands. “We are bringing communities together, making these adversarial roles more of partnerships and asking how conservation can be part of that.”

“We are bringing communities together, making these adversarial roles more of partnerships and asking how conservation can be part of that.”

Carmen Farmer, Colorado Open Lands

That shift in thinking resonates with Jim Yahn, manager of North Sterling Improvement Reservoirs and a board member of the Colorado Water Congress. Yahn has helped broker deals that keep water in agriculture while still meeting urban and industrial needs.

One early example: Xcel Energy’s Brush power plant requires 3,000 acre-feet of standby water in winter. Instead of buying rights outright, Xcel pays $150,000 annually to hold that water, with extra payments if it’s actually used. The arrangement provided farmers with income without permanently drying up land. “For farmers this was totally voluntary,” Yahn said. “It was the first time we did any kind of a deal outside of just using water for irrigation.”

That original deal brought in water speculators. These groups were searching for “first right of refusal” deals with ditch companies or farmers for buying their water rights, but those never made it to fruition, according to Yahn.

Agriculture in Colorado is a $47 billion industry, and rural economies are dependent on agriculture to stay vital and healthy. The money that comes in from selling corn, milk, peaches, hay or beef pays for schools, road maintenance and hospital bills, not to mention theater visits, restaurant tabs and fishing trips. By thinking of water as another commodity they have to market, Yahn thinks other opportunities can be unlocked.

“We want to push new ideas and get our farmers to think a little differently. We grew up in the area, we don’t want to see it go down the tubes to meet Front Range needs.”

Density as Water Policy

The shape of urban growth has direct implications for water demand. In arid regions, large-lot sprawl with green lawns is a luxury the resource can’t sustain. According to San Diego-based group Circulate San Diego’s 2015 study on infill development, large lots with big lawns consume a significant amount of water (50-70% of household water use is in landscaping and outdoor use) and pipes leak 6-25% of the water pumped through them, amounts that get worse with long distances.

Infill development—building more homes within existing urban areas—offers a far more water-efficient option. Smaller lots mean less outdoor use, shorter pipes reduce leakage, and fewer roads and driveways allow more rain to soak into the ground rather than running off.

Advocates say these lessons apply directly to Colorado. But zoning restrictions remain a major obstacle. According to Max Nardo and Robert Greer, organizers with YIMBY Denver, changing Colorado’s land use laws so this kind of efficient infill development is an option is an important part of solving the sprawl pressure pushing cities and counties to expand development and purchase ag land and water.

“Sprawl is not a revealed preference of how we want to live,” Nardo says. “It’s illegal to build denser housing and the types of housing in cities people want to live in.”

“Sprawl is not a revealed preference of how we want to live. It’s illegal to build denser housing and the types of housing in cities people want to live in.”

Max Nardo, YIMBY Denver

In 2023, Colorado lawmakers considered—but failed to pass—a bill that would have allowed more infill housing across urban areas. While some provisions resurfaced in 2024, progress has been slow. Without zoning reform, water-efficient housing remains out of reach for many residents.

And sometimes conservation measures are wolves in sheep’s clothing.

Aurora, for example, lowered its water requirement for new homes from three acre-feet to just a quarter acre-foot. That allowed more houses to be built but encouraged outward sprawl rather than denser, more sustainable development.

Ambitious, and expensive, partnerships

Collaborative projects between municipalities and farmers show another path forward. One of the most ambitious is the $780 million Platte Valley Water Partnership between the Parker Water & Sanitation District (PWSD) and eastern Colorado producers.

The plan calls for a 125-mile pipeline and new reservoirs with capacity for nearly 80,000 acre-feet of water. It will capture stormwater overflow from the South Platte River—flows that currently rush unused into Nebraska—and split them between Parker and local agriculture.

PWSD originally relied on the Denver aquifer and wells for most of its residential needs. As the population has exploded in PWSD’s 45 square mile jurisdiction, which covers a significant part of Denver’s south metro area, new water sources are needed.

For Colorado, and for the wider West, the future of housing will be measured not in acres of land, but in acre-feet of water.

“This could almost be the case study where an agreement between municipalities and ag can be a win-win,” says Rebecca Tejada, PWSD’s director of engineering. “50% of that water goes to Parker Water and the 50% stays in [agriculture]—water they didn’t have before.”

The catch is timing. Large-scale water projects take decades to build. With climate change reshaping precipitation and snowpack patterns, long-term supply planning is precarious at best. Still, such projects illustrate the creativity needed to balance growth with resource limits.

Water, Not Land, Is the Limit

Colorado’s experience underscores a lesson playing out across much of the West: available land isn’t the bottleneck to growth. Water is. Sprawling subdivisions can always be pushed farther into farm fields and rangeland—but without secure supplies, those homes are unsustainable.

The choices facing the state are stark. Continue business as usual, and farms will go dry, rural economies will hollow out, and sprawling cities will strain already stressed rivers. Or pursue denser housing, more flexible water-sharing agreements, and projects that serve both towns and farms. Creative agreements, smarter growth, and a willingness to treat water as the finite, shared resource it is offers the only path forward. For Colorado, and for the wider West, the future of housing will be measured not in acres of land, but in acre-feet of water.

Top Photo: Growth on former farmland in the Little Thompson basin in Northern Colorado.

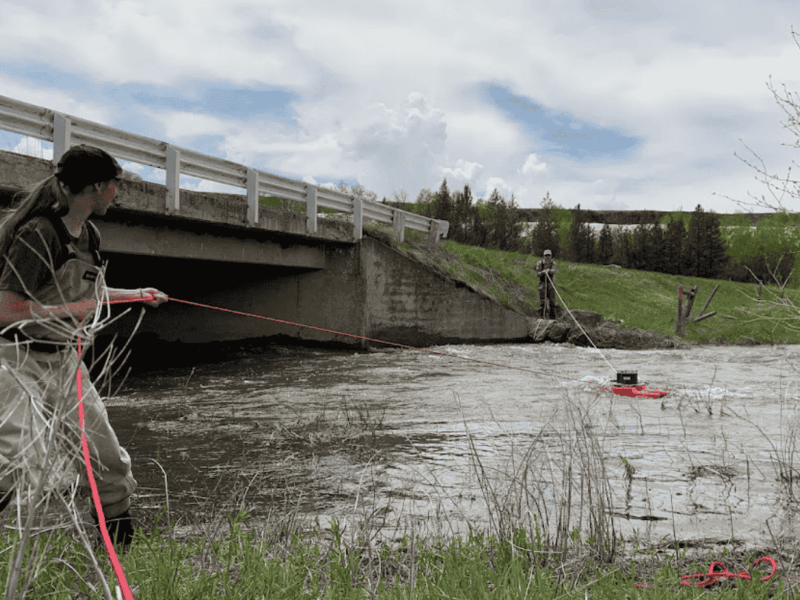

All photos courtesy of Colorado Open Lands.