By staying rooted in relationships with each other and the land, the Babbitt family kept their historic ranch together and secured its legacy for generations to come.

On a typical August day in Northern Arizona’s high country, monsoon thunderheads climbed on the horizon. Billy Cordasco looked out over the historic buildings of the Babbitt Ranches Cedar Ranch Camp and considered the harvest this land would bring generations to come.

These buildings had narrowly escaped wildfire last summer. Yet, as he gazed at the scene, Cordasco recalled a time three decades ago, when his family business, Babbitt Ranches, had felt the heat of internal and external pressures that could have dramatically changed the landscape of Northern Arizona and brought an end to the pioneering company. Harnessing that energy purposefully became the key to a durable future for Babbitt Ranches and the landscape they steward.

Recalling those tense moments 30 years ago, Cordasco, grandson of John Babbitt and now president and general manager of Babbitt Ranches, said, “You can expect family business to be messy at times. But it’s in those times that we remember what matters most. And that’s when great things can happen.”

The great things happening on Babbitt Ranches today include enterprises as diverse as cattle ranching, renewable energy, landscape-scale conservation, dark sky protection, scientific discovery, golden eagle conservation and recreation. That diversity, along with a focus on sustainability, has bred resilience, allowing the family to keep the land and business together.

Currently, the land company is working with four global renewable energy development companies to generate wind and solar power. The project with Clēnera, owned by Enlight Renewable Energy, will create the largest solar farm in the world, producing up to 1,500 megawatts of renewable energy for households while offsetting 1 billion pounds of carbon dioxide emissions each year starting in 2024.

“This direction in renewable energy takes into account all the different focus areas we have, including maintaining an overall healthy environment and participating in the broad global perspective while fitting into our landscape-scale conservation framework,” Cordasco said.

You can expect family business to be messy at times. But it’s in those times that we remember what matters most.

Billy Cordasco

The Pressure to Sell

Scott Hawes, Managing Principal Broker, Fay Ranches

The main reason we see long-standing family ranches selling is due to what I call a ‘generational shift.’

But this direction was not clear in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The Babbitt operations were a century old, and the family business was going through generational change. Cordasco’s grandfather, John Babbitt, was retiring as ranch manager after his 50-year career. Longtime ranch foreman Bill Howell was retiring as well.

“One of the things that was happening was the pressure to sell,” said Cordasco. “We had offers from neighboring entities, and there ended up being this big push for 40-acre developments.”

In this time of uncertainty, emotions were running high. Many Babbitts were very connected to the land and the day-to-day operations of the cattle business. And many were not. “We had to find a way to reach common ground,” said Cordasco, “or dissolve the company, something that had been a huge part of our identity our whole lives.”

The Babbitt family may be a particularly well-known family in the West, but what they were going through is not unique.

“The main reason we see long-standing family ranches selling is due to what I call a ‘generational shift,’” said Fay Ranches Managing Principal Broker Scott Hawes from his Oregon office. “Often, there is not an heir apparent that wants to continue with the ranching business, or there are several family members that own an inherited interest in the ranch but do not have the pride of ownership, motivation, interest or opportunity to be actively involved in operating the ranch and would like to cash in on their investment to spend elsewhere. This is often a third-generation issue, where a member of the second generation has stayed on the ranch and operated it, while siblings have moved off the ranch and pursued other careers, raising their children in an urban environment. As a result, they lose the connection to the family ranch.”

The Babbitt family brought in a real estate developer to show what 40-acre developments would look like across Babbitt Ranches, a 750,000-acre mix of state, federal and private land, and what selling the land might mean in terms of cash to the shareholders.

“It was a big upheaval for the family business,” said Carter Benton, a land consultant for the Ganado Group, the agricultural and rural real estate service company that works with Babbitt Ranches. “Subdividing large ranches had been going on since the ’60s in Northern Arizona, but by the ’80s and ’90s, there were barely any ranches like Babbitt Ranches left. and the family had received very viable offers. It was absolutely tempting for those shareholders who didn’t take part in the ranching operations, which didn’t throw off a tremendous amount of cash. In cases like this, shareholders often see the ranch as an asset they own but one they don’t derive any benefit from.”

For some family members, however, their hearts were breaking, as if the twisted old roots of their family tree were being ripped from the Arizona soil. For Billy, this was the place he had bounced along on dirt roads in his grandad’s pickup truck as a kid. It was also the site of a uniquely American story that began in a family grocery store thousands of miles away.

The Promise of the Future

We had to put something so far out there that it takes people out of their world and into a place where they can see something bigger than themselves.

Billy Cordasco

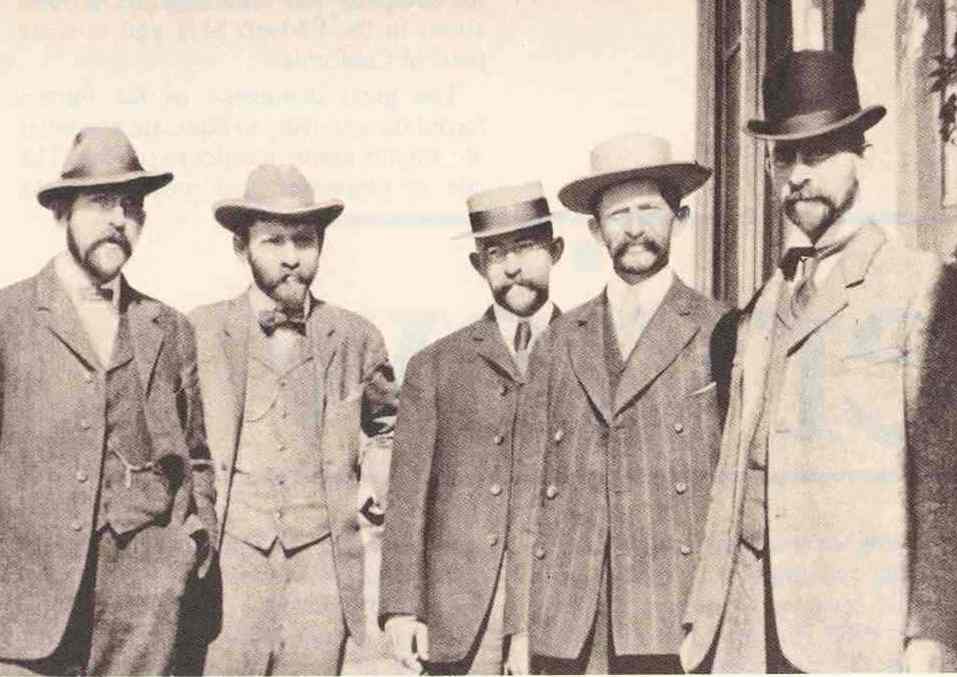

In 1884, five Babbitt brothers were selling groceries in their hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio, doing their chores and getting ready to close shop for the day, when suddenly a salesman burst in, brimming with enthusiasm and carrying brochures.

“As snow flurries flew from this exuberant visitor’s overcoat, the young men gathered around the potbelly stove in wide-eyed amazement to hear him gush with excitement about the adventure and promise of the West,” said Cordasco, enthusiastically recounting the story told to him by his cousin and family historian the late Jim Babbitt. “Eagerly presenting his brochures, it was clear to the Babbitt brothers this gentleman held the future in his hands.”

The pamphleteer had irrevocably sparked their imaginations. “I believe they understood they were saying yes for the chance to be part of something much bigger than themselves, to build communities, to participate in the growing agricultural industry and to help feed, clothe and build a nation.”

Cordasco said he felt that opportunity show up again, 100 years later, as the Babbitt family considered its future. He believed if the business were to continue into the 21st century, family members would have to find that “promise of the West” that they could all rally around. “We had to put something so far out there that it takes people out of their world and into a place where they can see something bigger than themselves.”

Identifying What Matters Most

To do that, they began to dig deep into their values. “This was a major turning point for us. We knew we had to say either yes or no to our future and define what that was going to be. This was the opportunity for us to articulate what mattered most.”

Faced with that decision to sell, the owners took it to a vote in the historic Babbitt Brothers boardroom in downtown Flagstaff. “It was absolutely remarkable,” said Cordasco. “It was unanimous not to go that direction. It was a benchmark. What it established was a new mission statement for Babbitt Ranches.”

Now that the first difficult decision to keep the ranch together was behind them, the family could focus on what they did want the future to look like. Much like when the pamphleteer burst through the doors of that Cincinnati grocery store long ago, Cordasco says, that boardroom vote sparked the family’s imagination of what the future could hold. The decision not to sell started the owners talking about a land-use ethic, which led to the creation of the science, research and educational nonprofit arm of the company, the Landsward Foundation. “Folks like Aldo Leopold and many others were very instructive in guiding some of that ethic,” recalled Cordasco, “but it got well-seeded in a family that already had it in them from 1886. It got reestablished and well articulated.”

They also discussed how to apply awareness, responsibility, obligation and a sense of accountability to their land-use ethic. “Of course, that included conservation stewardship, and most importantly, relationships, with ourselves, with each other, with the community and with the environment,” Cordasco said.

The family created the Constitution of Babbitt Ranches, in which the company defined its principles, values, purpose and “Cowboy Essence,” a description of core character qualities for how the company strives to operate and interact. It codified what the family called its “Multiple Bottom Line” philosophy. The philosophy allowed the business to pursue a number of creative endeavors with a wide variety of people and organizations.

One focus was on wildlife conservation. Babbitt Ranches became instrumental in projects that protect habitat for pronghorn, as well as bringing the most endangered mammal in North America, the black-footed ferret, back to the grasslands of Northern Arizona. Notably, in 2001, Babbitt Ranches executed one of the largest conservation easements in the country, in which the Babbitts donated a portion of Cataract Ranch — 34,480 acres of spectacular canyon country between the Grand Canyon and Flagstsaff — to Coconino County and The Nature Conservancy to be set aside for open space in perpetuity. In 2021, they created the S P Crater Golden Eagle Conservation Complex to promote the study of these large raptors and protect their nests and prey base.

Within the set of principles the family created, scientific research and space exploration projects for the sake of education and knowledge became another focus. Babbitt Ranches could play a larger role in scientific discovery by opening the gate of its private land to climate change research, cultural site stabilization and space exploration.

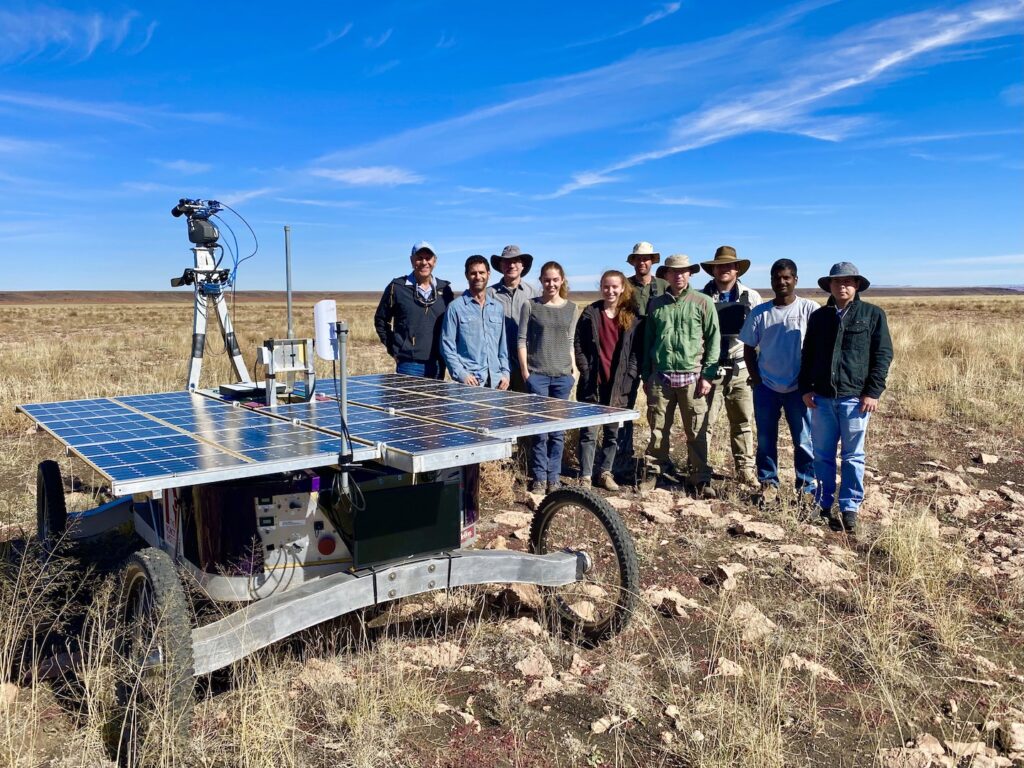

As part of an emphasis on scientific discovery, the family welcomed NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory back to Babbitt Ranches. As engineers, astronauts and geologists had tested moon rovers and trained in spacesuits on the rocky terrain during the 1960s Apollo missions, they returned to Babbitt Ranches on a regular basis in the 2000s to try out rover prototypes, communications systems and space gear alongside Babbitt Ranches Hereford cattle. Operating on private land simplified the process for administrators, as they didn’t have to seek permission from state and national parks or forest land to operate.

There was now also room in the family business to expand recreation opportunities, including allowing for the Arizona Trail to stretch through the ranches. High desert recreation opportunities were seen as a revenue source. Babbitt Ranches hosts The Stagecoach Line 100, an ultrarunning test piece. By 2015, the alignment of recreation with the business was so well established that Babbitt Ranches acquired Arizona Nordic Village, a cross-country ski area in the Coconino National Forest neighboring the ranch.

Relationships are all there is

We didn’t know what all the future held, but we defined ourselves through our values and guiding documents so that when opportunity showed up, we could recognize the fit and embrace it.

Billy Cordasco

Cordasco says the greatest challenge to agriculture and land ownership is the transition through turbulence, moving away from what is certain to what is uncertain. The key to succession, he says, is having the framework, the paradigm and the context in place that defines how the company will engage through time. For Cordasco, ultimately, that framework is made of relationships. In the Babbitt Constitution, at the top of Article IX, Priceless Values, Cordasco is quoted: “With yourself, with family and friends, with the community and with the environment, one way or another and in the end, relationships are all there is.”

“It took time, patience and understanding on the part of the Babbitt family members to try to find out what each side wanted,” said Benton. “They also had to consider the value of these wonderful land assets; how they could maintain them and show others how to do it.”

“We didn’t know what all the future held, but we defined ourselves through our values and guiding documents so that when opportunity showed up, we could recognize the fit and embrace it,” said Cordasco. “We were again positioned, excited and open to be part of something bigger than ourselves. So, when these renewable energy development companies showed up with the future in their hands, like that fella in the grocery store so long ago, we were ready to participate!”

As Hawes noted, “Unless pressured by other owners, we do not often see ranchers that love the land, the wildlife, their livestock and livelihood become interested in selling just because their land values have skyrocketed due to development demand.”

“We defused the pressure and regained our direction by focusing on our values, our land-use ethic, the importance we place on relationships and the desire to make decisions that will benefit future generations and set them up for opportunities to come,” said Cordasco. “For us, it’s about recognizing the moment when that ‘Go West spirit’ catches fire, ignites our enthusiasm and fans our imagination about participating in something bigger than ourselves.”