Flood Irrigation Can Lead to Better Streamflow, Study Says

The conversion of flood irrigation to sprinklers has been a boon to producers. Sprinklers are more efficient, which means better yields, and better yields mean more to sell on the market. But that conversion can come with the loss of a significant number of ecosystem services that flood irrigation provides. In eastern Idaho, that loss has had some definite costs for one of the world’s great dry fly fisheries.

The Henry’s Fork of the Snake River in eastern Idaho brings anglers from all across the globe, supporting a $50 million recreational fishing industry. Around this angling paradise is an extraordinarily productive $10 billion agricultural industry that relies on irrigation to grow alfalfa, barley, and famously, potatoes. At the Henry’s Fork Foundation (HFF), a watershed conservation organization that uses science-based collaboration to preserve the Henry’s Fork fishery, flood irrigation has outsize importance for their goals.

Ag-MAR Provides Long-Lasting Effects

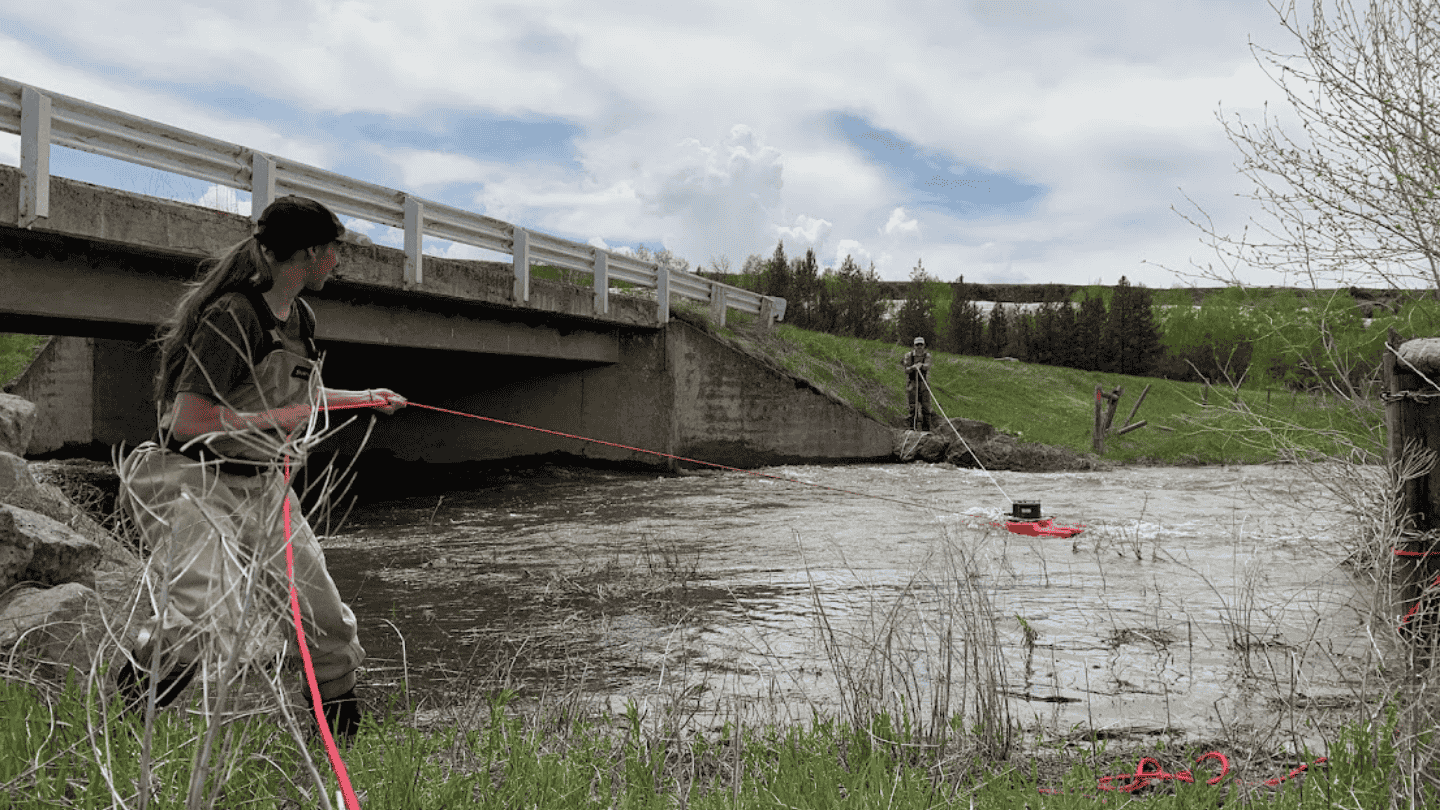

Christina Morrisett, HFF’s climate adaption program manager with a PhD from Utah State University, led a 2024 study that investigated whether an old agricultural landscape could offer a new way to recover groundwater return flows in the Henry’s Fork. By simulating 30 years of future water supply conditions and local water management rules, the study explored the potential of agricultural managed aquifer recharge (Ag-MAR), a practice that uses the existing irrigation canals and agricultural fields, to divert excess streamflow, such as floods and snowmelt, for artificial groundwater recharge

“Originally we were looking at the history of irrigation efficiency—from flood to sprinkler conversion—from 1978-2022, to see why folks converted, when they converted, and what the impact was on the river as a result,” Morrisett said. Historical research showed that from 1978-2000, that conversion process decreased the return river flow by 240,000 acre-feet.

“The question then was, how can we recover groundwater return flows,” Morrisett said. Downstream water users rely on the recycling process of flood irrigation, as do trout and other species that populate the Henry’s Fork. Groundwater recharge contributes to increased streamflow and provides cold water needed by fish to survive hot, dry summers.

The state of Idaho has made some strides toward managing aquifer recharge. In the late 1990s, the Idaho Water Resources Board began claiming managed aquifer recharge rights, which use flood irrigation techniques to get more water underground. The problem, according to Morrisett’s paper, is that in a drying climate, those rights only become available in the very wettest of years.

And there’s another issue.

“According to modeling, the wettest years become less and less common,” Morrisett said.

There is some good news, however. If senior water rights holders used the maximum amount of flood irrigation available to them in the model, the Henry’s Fork would see substantial gains in its streamflow throughout the year.

“Conducting Ag-MAR reduced peak springtime streamflows by 10%–14% but increased summer streamflow by 6%–14% and winter streamflow by 9%–14%. Thus, Ag-MAR can effectively recover groundwater return flows in our study area,” the study reported.

This study shows the value of collective effort, as long-term protection of an important ecological, recreational, and agricultural watershed will need every group pulling the same way. All that needs to be done is following the oldest irrigation trick in the book.

Read the Studies

Morrisett, C. N., Van Kirk, R. W., & Null, S. E. (2024). Can Agricultural Managed Aquifer Recharge (Ag‐MAR) Recover Return Flows Under Prior Appropriation in a Warming Climate?. Water Resources Research, 60(8), e2023WR036648. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2023WR036648