Dryland Farming in the Colorado Basin with Gus Westerman

In a drying West, more producers are looking for options to remain viable, which is why today we’re taking a look at dryland farming.

Relying on water from the sky in the Colorado River Basin, where it feels like irrigation is the norm, is not an easy task. That’s why we’re chatting with Gus Westerman, director at Colorado State University Extension and drought advisor, to learn how to make farming economically and ecologically viable in a part of Colorado that puts the “dry” in dryland.

listen

Links from this episode

Dolores County CSU Extension: https://dolores.extension.colostate.edu/

Dolores County’s Famous Beans: https://www.anasazibeans.com/

USDA Crop & Livestock Insurance: https://www.usda.gov/farming-and-ranching/financial-resources-farmers-and-ranchers/crop-and-livestock-insurance

Western SARE & CSU: Examining Cover Crops for Soil Health Restoration in Dryland Cropping Systems in SW Colorado and SE Utah

https://projects.sare.org/project-reports/sw18-500

WLA: Rancher Innovations to Support Soil Health and Water Management as the Climate Changes https://onland.westernlandowners.org/2024/stewardship-in-action/rancher-innovations-to-support-soil-health-and-water-management-as-the-climate-changes/

WLA: How to Increase Soil Health and Productivity in Two Years

WLA: Soil Solutions to Water Scarcity: Making the Most of Every Drop

Transcript

Zach Altman: [00:00:00] Welcome back to the On Land Podcast. I’m Zach Altman. We’re here with another On Land, On Water episode, which is our miniseries about all things water in the west. Joining me today is Thomas Plank. Hey, Thomas.

Thomas Plank: Hey, Zach.

Zach Altman: What are we getting into today?

Thomas Plank: We are visiting Dolores County Colorado to talk with Gus Westerman, who’s a Colorado State University extension officer who does a lot of work with dry land farmers in what is known as the bean capital of the world.

Zach Altman: Excellent. And why are we even talking about dryland farming anyway?

Thomas Plank: Dry land farming is a style of agriculture that doesn’t rely on irrigation. Dolores County is in the Colorado River Basin, but I’m interested in how people can or are doing agriculture without relying on irrigation from the already over allocated Colorado River. Gus was a perfect person to talk to about this because we go into changing [00:01:00] weather patterns, the monsoon, and all of the interesting things that come along with it ’cause really dry land farmers are moisture farmers at their heart.

Zach Altman: Great. Well let’s just roll into this, uh, conversation with Gus Westerman.

Thomas Plank: Thanks, Zach. Appreciate it.

Zach Altman: Well, great. Let’s just dive in.

Gus Westerman: They always say our dry land farmers, they’re really farming moisture at the end of the day.

It’s much like a cattle rancher, you know, considering themselves a grass farmer, you know, as far as okay, we’re, yeah, sure we’re raising cows, but to raise those cows we’ve gotta raise grass. with our dry land farmers. Farming that moisture and managing that soil moisture is, very, very critical.

Thomas Plank: Gus Westerman is the guy you go to when you have a question about agriculture in Dolores County, [00:02:00] Colorado. He’s the county Extension Director for Colorado State University Extension, and he grew up here in Dolores County. Gus has both experience working on the range as he spent three years working for the Southern Ute Tribe as a range light and technician before he began at CSU back in 2014.

He is the person you would reach out to if you had a question about say, how to do dry land farming at all.

Gus Westerman: So dry land farming is raising an agricultural product without irrigation. So therefore dry land farming is all about managing your soil and your soil moisture to raise a crop, whatever that may be, whether it be a row crop, whether it be a forage crop. But you’re raising an agricultural product without the use of irrigation, so you are dependent on natural precipitation for your water.

Thomas Plank: So I think for a lot of people they would [00:03:00] assume that, Colorado and a lot of the Western states relying on precipitation from the sky isn’t. doesn’t seem the most rational, for a lot of places, that is the only way that people are going to get water. Is that correct?

Gus Westerman: That is correct and it depends on where we’re at. So in Southwestern Colorado we do have some amazing water resources and especially down in say like Montezuma and La Plata counties being great examples of some really, old irrigation projects that have been functioning for, over the last a hundred years almost.

So they have some really great irrigated ag base. However, there’s a lot of other portions within, say, Southwestern Colorado, the front range of Colorado that don’t have access to those water resources. And so those ag bases are completely reliant on natural precipitation and, so [00:04:00] it, it really depends on location and Dolores County’s a great example of that.

About 80% of our crop land base is dry land. We have about 7,000 irrigated acres within Dolores County. Yeah, the rest of that is the rest of that ground in crop production is dry land.

Thomas Plank: Okay. And Gus, for people who haven’t been to Southwestern Colorado. What does Dolores County look like? Is it a lot of mountains? Is it mostly plains? Is this turning into that red rock desert of what people would assume of Canyon Lands and Moab? Or what are we looking at here?

Gus Westerman: Great question. So Dolores County is extremely diverse. Um, It’s a uh, if you look at it on the map, it is a uh, it’s a long, narrow county.

so the Western portion of Dolores County, which borders the state of Utah. The next town right over into Utah is Monticello. And, uh. so we are predominantly right around that 6,900 [00:05:00] to 7,100 feet, and we call that kind of the great sage plain area.

That’s where most of our crop production takes place. As we move further east into the middle portion of the county, we get up to elevations anywhere from eight to 9,000 feet, where we have a lot of uh, a lot of range land, a lot of forest service land. Um, So a lot of livestock grazing takes place. And then further east you get up to where the town of Rico’s located.

And, uh, the town of Rico’s located about 9,000 feet in elevation. And uh, you get up into that higher alpine. And so we actually do have uh, El Diente, which is our 14,000 foot peak. And so we range from the bottom of Disappointment Valley, which is about uh, right around 6,000 feet at our low point all the way to 14,000 feet at our high point.

So, yeah, once again, very diverse county.

Thomas Plank: Disappointment Valley and the Tooth. So a well named county as well, it seems

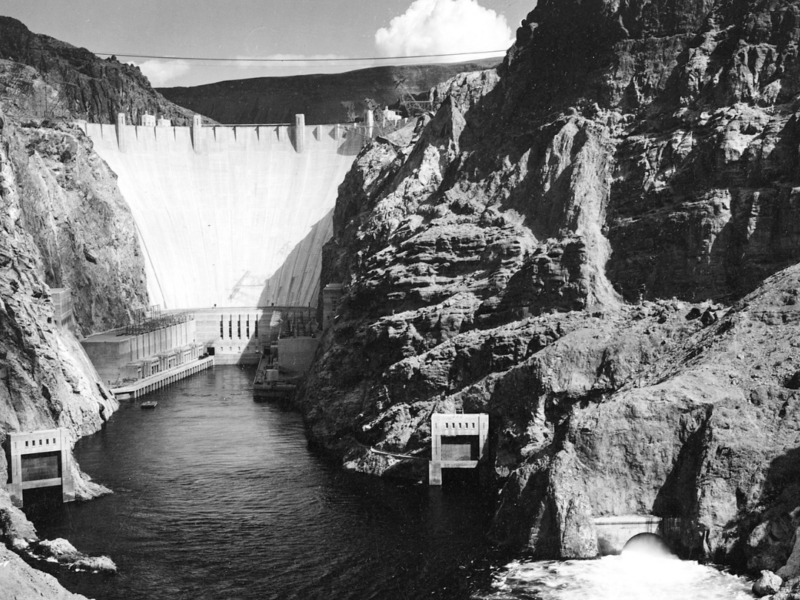

Gus Westerman: [00:06:00] yes, that’s correct. And uh, yeah, the county’s named for the Dolores River. So the, the headwaters of the Dolores River um, take off from Lizard Head pass up on the east uh, then flows down into Montezuma County through the town of Dolores and then uh, into McPhee Reservoir and then uh, out of the McFee Dam.

Then it flows back north through Dolores County and then into San Miguel County.

Thomas Plank: Great. Thank you so much for that geography lesson. Gus. The next question, and I think the one that’s gonna prime us for this conversation about dry land farming is how much rain does Dolores County average in a year? Or I guess not rain, but precipitation?

Gus Westerman: Yeah, that’s perfect. Yeah. Precipitation. We average right around 11 inches per year. That’s our, that is our current 30 year average is right about that 11 inches. And of course that fluctuates greatly from year to year.

Most of that comes as snowfall over the winter months, we receive [00:07:00] a, a few inches of that through um, monsoonal patterns that usually kick off late June through July.

Into August and uh, of course recently those monsoons have become pretty unreliable. And so really we are very dependent on our winter moisture.

Thomas Plank: From our first definition of dry land farming. Rainfall seems to be the main driver of, keeping your crops growing, particularly in those hot summer months. But for Dolores County and I think a lot of the West, as you’ve said, so much of this relies on winter precipitation, which it also seems leads into the next thing, which is soil moisture, and soil health.

how much does making sure that your soil is healthy and able to hold water matter for the economic viability of farmland?

Gus Westerman: Uh, it’s critical. Um, so soil moisture is, uh, once again it’s, we [00:08:00] look at water, especially in, uh, this arid region in southwestern Colorado. Water is our most limiting nutrient. And um, I have a few stats just to kinda show that with some wheat yields, which, which we can talk about here in a minute. But, uh, yes, water is our most limiting nutrient, and the timing of that precipitation is also very critical depending on what crop you’re growing. And so that’s one of the biggest differences that. Us here in Southwestern Colorado Sea as opposed to some of those areas, say in the, in northeast Colorado, out on the plains there, they have a much more reliable monsoon season, where we’re at over on this side, we are far more similar to say Northeastern or Northwestern, Utah, Idaho, some of those areas. And so therefore, a lot of the crop management varieties we’re growing, types of crops we’re growing are more similar to what you would see in, kind of some of those Utah [00:09:00] crop production areas than say the plains of Colorado.

Thomas Plank: Morgan Wagner is WLA’s Water Program director. She’s the person I go to whenever I have one of my many questions about the Colorado River Basin and her Kenai for details and her legal and scientific background means she can assay the huge amount of stuff happening at any given time and come up with a clear and concise distillation of what’s really going on.

I brought her on today to talk about why dryland farming is something we should be talking about, and how silver buckshot is the best answer for the water problems in this part of the world.

Morgan Wagoner: Hey Thomas, how’s it going today?

Thomas Plank: Good, how are you?

Morgan Wagoner: It’s another beautiful sunny day here in the Southwest.

Thomas Plank: Morgan, Gus and I have been talking about dryland farming and Gus is also in your neck of the woods in the Southwest. Um, but one of the things that he and I were discussing is, or [00:10:00] rather. That has come up as we’ve been working on this podcast is why are we talking about the issues that we are, um, and the real reason is the Colorado River Basin.

So Morgan, I’m gonna ask you some questions that are going to be pretty, pretty big ones, but I think the most important one is what is going on with the Colorado River Basin right now and as we are moving into 2026.

Morgan Wagoner: Yeah, so the Colorado River Basin is currently reevaluating the operating guidelines for how the federal infrastructure is managed, but that has not on effects for all of the states and anyone who uses Colorado River Water. And how, what those guidelines dictate is gonna determine potentially how much water any water user has access to.

And the one thing that we know for sure is that [00:11:00] we have less water in the basin and there’s not enough to go around. So we’re gonna see shortages. And how do Landowners specifically and agricultural operations maintain their economic feasibility as they face these shortages? And what sort of.

Techniques can be implemented to both protect the land as well as their operations.

Thomas Plank: So basically what you’re saying is, and for people who aren’t familiar with the history of the Colorado River Basin. In 1922, they made a compact, the Colorado River Compact that had a certain amount of acre feet every single year that was divided among seven states and Mexico. Is that right Morgan?

Morgan Wagoner: More or less we actually, our 1922 compact. Divided the Colorado River water between the upper and lower basin with the dividing line at Lee Ferry. [00:12:00] And then in 1944, we made a compact with Mexico and that gave Mexico their allotment. But the long story short, whether you’ve got the timeline or anything, is that we allotted 7.5 million acre feet to each basin, and then an additional 1.5 million.

To Mexico and there are additional intricacies. If you add everything up, you get somewhere around 18 million acre feet and that doesn’t exist.

Thomas Plank: And that leads to that, how many acre feet are actually in the Colorado River Basin on an annual basis. And this is just like a guesstimate, Morgan, I’m, I’m not looking for the, the exact number here.

Morgan Wagoner: I mean the, obviously it’s highly, highly variable and it depends on how you’re measuring it, but somewhere around 12 million acre feet is what we are probably looking at, [00:13:00] but. We’re trending and there are leading scientists who have warned that we could be looking at more like a 10 million acre foot river.

Thomas Plank: So that’s. Half basically, of what was originally allotted.

Morgan Wagoner: Not quite half, but it’s, it’s a very significant deficit that we’re running.

Thomas Plank: So again, the reason we are talking with Gus about things like dry land farming, which doesn’t rely on irrigation or are thinking about things like rock weers, which we just, uh, discussed with Eric Kalsta is. WLA is interested in other ways of existing in these complicated situations. Um, and Morgan, I mean, I’ve, I’ll let you speak to this, but one of the biggest parts of our mission is for whole and healthy working lands [00:14:00] and ecosystems, uh, and the lack of water in the Colorado River Basin.

It is not just gonna have knock-on effects for, you know, like Los Angeles or Denver, or where people are getting their tap water, but it also is gonna have some pretty serious effects on the ecology of the entire Southwest.

Morgan Wagoner: Yeah, and I think that that’s one of the really important pieces of this really complicated puzzle. The fact of the matter is that there’s gonna be less water, and so there’s gonna be less water on the landscape. But removing water from the landscape has really detrimental effects on a lot of things. Um, when we see fallowed fields, we see increased dust on snow events.

We see decreased soil health. Decreased ability to retain water when you don’t already have water. So we have all of these knock on effects that we’re gonna be seeing [00:15:00] in the basin as we see these shortages increase and extend. And so how do we adapt to that? And how do we make sure that we are maintaining those whole and healthy landscapes that support both people and wildlife.

Thomas Plank: And so with what Morgan just said, that also means that things like the switching from irrigated lands to dry land farming. That’s not a simple thing. It’s not one that you can just go, oh, I’m gonna stop irrigating one year and then the next year I’m gonna shift to dry land because of those knock on effects.

So what the more important thing is nothing that we’re actually doing in this podcast is a simple solution, which I think is just the biggest problem with the Colorado River Basin. There are no simple solutions.

Morgan Wagoner: Yeah, I think, I mean the, the thing that everyone likes to stay in the basin now is it’s, uh, silver buckshot. We’re gonna have to put all of the tools that we have to use to weather through [00:16:00] as we redetermine how we’re using water in the west.

Thomas Plank: Silver buckshot, which I mean, that’s the. That’s the clearest you’re gonna get on this one, folks. Uh, thank you Morgan. And with that, let’s get back to Gus and talking about dry land farming.

Morgan Wagoner: Yeah. Thank you.

Thomas Plank: Okay, now back to Gus.

So what kind of crops are being grown in Dolores County?

Gus Westerman: So currently on our dry land base, the big ones, winter wheat is a staple, always has been. Safflower is another crop that has really dominated a lot of the acreage. And uh, dry beans. Of course, dove Creek is considered the pinto bean capital of the world. And so we do still have a lot of dry bean production here.

We don’t have nearly as much, and we do see acreage of dry beans dropping every year for a number of different reasons, which we can talk about. But of course dry beans are really what made our [00:17:00] area famous, and that’s what we’re known for. also we’ve done a lot of other oil seed production in the past.

Sunflower used to be a really big crop in the area. We’re not seeing nearly. The acreage of sunflower uh, safflower, which is also an oil seed crop, has really. Kind of Dominated that. And uh, there’s a lot of reasons there as far as um, equipment needs and things. Um, So you can use a lot of very similar equipment for um, winter wheat and safflower.

You’re not really having to retool where if you’re getting into other crops like dry beans and sunflowers, then you’re getting into very specialized equipment that are. Typically only used for those crops. And so that’s one reason why we really see our rotations more dominated by that that winter wheat safflower and then a fallow period rotation.

Thomas Plank: So a couple of things then. It seems like if I was a farmer and I was thinking about the [00:18:00] economic, landscape of the world, I would be a little concerned to be fully relying in southwestern Colorado on precipitation as my only water source.

How are farmers and people who are reliant on these kinds of dry land techniques? Thinking about, their futures or their crop rotations or those kinds of things, like how are they balancing trust in natural cycles and what they can do on the ground.

Gus Westerman: That’s a great question. And in any farming operation, the first thing is farmers, are business folks and a farm is a business and has to be run as a business and. So whenever we’re looking at growing a crop, the first consideration is, can we grow this crop? And if the answer’s [00:19:00] yes, we can viably grow this crop.

The next question is, once we grow it, what are we gonna do with it? Another challenge we face in southwestern Colorado is we are very, very isolated. And so we have limited access to the markets and especially where we’re growing um, some of these commodities. Wheat being a great example. Those markets are nowhere close to us.

So those, that product has be transported out of the area which is expensive. so our access to markets is limited, And also it limits the crops that we do grow. We grow crops that we know we have an outlet for, that we know we have a market for. And so that makes it challenging to really look at alternative crops because that’s one thing we’re always looking at.

We’re looking at alternatives of what other crops can we viably grow that we can make money off of? But then it’s if we don’t have access to that market, then that crop is not viable. So there’s [00:20:00] always that business side. And there’s also a lot of risk management that goes into crop production.

And a lot of our producers are enrolled in USDA safety net programs, such as ag risk coverage, price loss, coverage. Then there’s the USDA’s risk management agency that supports that actually subsidizes some of our private insurance. They offer different risk management products like say rain and hail coverage being an example.

Thomas Plank: If you’re interested in what exactly Gus is talking about in regards to these agencies, don’t worry. We’ll link to some of those programs in our show notes.

Gus Westerman: Therefore, if you have a natural. Impact like a hailstorm or severe drought that impacts your crop. There’s a safety net there for those producers. So that business side is extremely critical and it has to balance with the production side. [00:21:00] And so we can just talk about and we’ll get back to our soils here.

And so once again. Our soils within Dolores County here, it’s predominantly weather alone. And it’s a very special soil. It is, it’s a loess soil. So meaning it’s it was blown in and deposited here, but the makeup of that soil is a silty clay loam. And the reason that’s important is that high.

Percentage of silt within our soil with that clay component allows our soils to hold water very, very efficiently, and that allows uh, our dry land ag production to be possible. In this area. However, management is such a big part of this they always say our dry land farmers, they’re really farming moisture at the end of the day.

It’s much like a cattle rancher, considering themselves a [00:22:00] grass farmer, sure we’re raising cows, but to raise those cows we’ve gotta raise grass. with our dry land farmers. Farming that moisture and managing that soil moisture is, very, very critical.

at the end of the day, we’re looking at different crops and rotations that we do manage that moisture. So for example, a common rotation in Dolores County would be a year of winter wheat. So winter wheat is planted in the fall, typically September being the ideal time.

That uh, winter wheat, it comes up in the fall and uh, it gets to a stage where it can survive Winter dormancy. So it goes dormant through the wintertime and as soon as things warm up in the springtime, it uh, has a flush of vegetative growth and it uh, then essentially goes reproductive, puts on that grain and that grain’s harvested in about late July.

Following that, the following year. Our [00:23:00] producers will typically go to a crop like safflower being an oil seed crop. The difference is safflower is planted in the early springtime, using that winter moisture to grow. The great thing about safflower has a very deep taproot. Therefore, that plant can utilize moisture and nutrients that were below that rooting zone of the winter week.

So you’re essentially getting two crops off of that soil moisture. The next period after that safflower is harvested, then you go into a fallow period. And that fallow period is very important because you are essentially storing a full year of moisture with no crop growing on that ground. And once you get through that fallow period.

Then you can go back in with your next crop. So if you look at water needs of some of these crops, winter wheat being right around 16 to 17 inches of moisture [00:24:00] for a really good crop you wonder, okay, so how do we grow a dry land crop with a requirement of 16 inches of moisture? On 10 to 11 inches of moisture.

The reason is that fallow period, we’re storing an extra year of moisture within that soil to make that production possible.

Thomas Plank: That’s very clever. It’s also very interesting to think about how. Soil depth and root depth matters so much for these kinds of decisions. Actually one thing I am curious about too, Gus, is in those fallow periods, are farmers stopping weeds from taking over that dry land area?

Gus Westerman: So a number of different ways. Um, Traditionally. Tillage um, has uh, been that main form of weed control. And uh, of course our ag system in southwest Colorado. [00:25:00] We’ve been heavily reliant on tillage for generations now. Things are changing now whenever we get into some soil health discussions, that’s.

Tillage is gonna be a big part of that. So tillage being one of the main tools. Also herbicides being the next tool the goal is to keep that land clear. You really don’t want anything growing in that because any plant that’s in there is utilizing moisture. And once again, we can talk more about soil health and different.

Different things like cover cropping and some of those things that have been really successful in other parts of the country and why those are really challenging for us here. However, if you go to say more on the eastern slope, you’ll see a lot more no-till. Which is a different management practice and no-till production’s very heavily reliant on herbicides for controlling those weeds during the fallow period because no-till tillage is not an option.

However, one thing um, just [00:26:00] um, because of our isolation and uh, difficult access to markets and also lower average production within our region. Folks really try to maximize the income off of every acre. And one way to do that, we see a lot of certified organic production especially certified organic wheat production here in Dolores County and southeast Utah.

What the deal with organic production is, tillage is your only form of weed control and soil management herbicides are essentially taken out of the equation, and so you’re essentially going back to say the more traditional farming methods. In the area. So organic production can be a little bit tougher on the soil because you’re so reliant on tillage.

However, even a lot of our conventional producers still [00:27:00] use tillage as a primary tool.

Thomas Plank: Interesting. Thank you. Okay. So very useful stuff and then I think with that we can probably get into the soil health discussion. Because I think, again, like from what I’ve learned in my time, my short time in this particular position is that everything is way more tightly interconnected than you might expect it first.

And when it comes to rain and precipitation, the health of your soil matters a lot for making sure that actually stays around and provides. Long term benefits to your land and the land around you.

Gus Westerman: Absolutely. Yes. Soil health is uh, it is a very big topic and it’s a very important topic, and it’s a topic that we have been um, working on [00:28:00] for, for, for years now. And of course, CSU is very focused on soil health. Soil health is a, um. it is a huge topic area for study. Um, We put a lot of resources into it.

Um, and, And really whenever we’re looking at soil health, there’s a lot of different ways to look at that. Um, Mainly whenever the big, the big things with soil health that you’re looking at, the metrics so to speak, would be one level of organic matter, which essentially is, um. that uh, that carbon based um, organic matter that’s in the soil, typically our soils tend to be very low organic matter.

Naturally, we run right around a half a percent to 1%. An elevated level for us here would be about maybe one and a half. Is would be a, typically a high level for Dolores County. The other side of soil health is microbial activity and [00:29:00] microbial activity. That would be the bacteria, the fungi that exists in soil that essentially help to break down residues and help to increase that organic matter within the soil, but also.

Form those symbiotic relationships with the plants that are in the soil. All of those kinds of things. And once again, just being in that desert, southwest area. We’re very arid. Therefore our microbial levels tend to also be pretty low. And there’s a few, few things that can really impact that.

One is our precipitation, just really warmer temperatures. Dry soils are not a great habitat for those soil microbes. So that’ll lower that activity. Then things like heavy tillage. A lot of soil disturbance also can impact those microbial communities. And then once again, looking back at organic matter, the importance there is.

Higher levels of [00:30:00] organic matter allows soils to hold more water, and that is one of those critical points, elevated organic matter. You’re going to increase your water holding capacity, which obviously within a dry land crop production system. Is very important and that is becoming really top of mind for a lot of our producers.

one great example is one thing that you’re seeing a shift, especially in our dry land region here. Our tillage practices to where we are starting to move towards that minimum tillage system. And by minimum tillage, we are trying to till less. We’re also trying to leave crop residues on that soil surface to help armor that surface from wind and water erosion.

So we’re trying to limit soil losses there. And also that residue will slowly break down [00:31:00] and. Over time, increase that organic matter. Now, some of the practices that have been really successful that are really hot topics, very popular to talk about cover cropping being a great way to enhance that organic matter and also enhance your microbial community.

You’ll always hear, you always need a living root in the soil to support that microbial community, and that is very true. Cover crops being a way to do that. And, in 2015, we actually started,

Gus Westerman: we did a five year study and it was funded by Western sere Sustainable Ag research and education program through USDA.

Thomas Plank: If you’re interested in some of the scientific background on soil health, we have some tools and WLA packaged kits that can point you in the right direction. Check our show notes for those links, and don’t worry. We’ll link to that [00:32:00] study that Gus just referenced in our show notes as well. We.

Gus Westerman: And we looked at dry land cover cropping and our goal was to what are the impacts of replacing that fallow period where you have bare soil with a cover crop? And so we tried a lot of different kinds of mixtures. And every mixture would usually have an annual grass, an annual broadleaf.

Usually a legume to maybe try to get some natural nitrogen back in the soil. But what we found our cover crops did great. They put on great biomass. However, the cash crop following that follow period. Was severely impacted. And yields were really impacted because that cover crop was utilizing that soil moisture through the fallow period, and we were never able to build that moisture level up to uh, [00:33:00] fulfill the needs of the following cash crop.

And so therefore, once again, it can be a great practice and. We do believe that over a period of 10 to 15 years you could possibly build your organic matter enough to where you could offset those water issues. However, that would mean the producer taking a loss on that acre for 15 years, which just would not be possible.

We come back to the business end. If you’re gonna continue farming, you have to stay in business and you cannot afford to lose money for 15 years before you see a return.

Thomas Plank: Yeah, that is, that, that is a long time. That is a, that’s half a half a 30 year mortgage of not seeing returns, which is not that’s beyond not insignificant. That is in the very significant level right there. And [00:34:00] this is, a lot of the What I would assume is conventional wisdom of oh, you need nitrogen fixers.

There needs to be clover on there. There needs to be these cover crops. It seems like in dry land farming, some of that conventional wisdom is turned on its head, but it also pops up in other ways too. What are some of the kind of most. Surprising things that you’ve picked up in learning about dryland farming in Dolores County in your time?

And are there any things that you know for people who might be interested particularly, and I think that certified organic style of farming that they’d want to use dry land or you know, maybe a water right, really isn’t possible. What are some of the things that they should. Or consider before starting down this path.

Gus Westerman: Absolutely. So that’s a great [00:35:00] question. So I, I would say that if you’re looking to uh, to get into dry land farming, so once again, looking at, at the area that you’re looking to locate to. Um, Once again, getting into agriculture period is very, very difficult. It’s very expensive. Um, If you’re starting with nothing, essentially um, the first thing is you have to come up with land.

And most folks that are just getting into it will lease. Their land to begin that. So once again, looking at land that’s available for lease looking at the historic production of that land is the next thing to really start making your plans. But then looking at, once again, the crops that you want to grow, but looking at markets, if you grow a certain crop, will you be able to market that crop is probably one of the biggest things to look at.

Then looking at the safety net programs that are gonna be available to you. So [00:36:00] okay. If this happens, if we do go into drought, if. We what’s my safety net if my crop fails, essentially. Those are all things that really need to be thought about. So in Dolores County, if, we’ve done.

And this was this was done by my predecessor which would’ve been probably 15 or 16 years ago, but our economic development organization here in Dolores County did uh, it was just a, just a minor analysis looking at the profitability of dry land farming. And at that point they determined that, and this would’ve been right around 2010, they determined that to break even.

You would’ve to farm essentially 800 acres. So that’s a lot of land and it’s a lot of land to buy and it’s a lot of land to lease. And so what we see is our average the average size of our producers here within the county. With our dry land crop farmers, they’re farming [00:37:00] anywhere from 1500 to 5,000 acres, give or take.

And a lot of that land is not owned by them. A lot of that land, like if you look at a parcel map of Dolores County, you’re not seeing too many 5,000 acre parcels within our crop base. And so they are they’re leasing a lot of land their land’s. Really cut up. So they’re farming fields in different places and uh, they’ve got a lot of landlords.

And uh, some of our producers, you know, they may have multiple landlords on one field. And so there’s a lot of uh, those complexities that, that come with that, you know, different leases on a single field, you know, that can cause its own complications of course,

Thomas Plank: That sounds the headache of all headaches too.

Gus Westerman: Absolutely. And with different landlords, you’re looking at different personalities, different wants, those kinds of things. And so there’s a lot that goes into it whenever you’re, somebody’s looking to get [00:38:00] started and it’s really. It’s not an easy, it’s not an easy thing to start.

But what really has surprised me about dry land farming, especially in Dolores County, is the resilience of our producers and the ability of our producers to. Adapt to some of these changes. And a great example would be their ability to adapt to adding safflower to that crop rotation.

Identifying that, wow, okay, we have a market for this crop. We can sell it and we can grow it. And it also adds a great functional plant into that crop rotation. To allow success. And I actually, whenever I first started in this position, there was still there was a lot of sunflower acreage at that point.

And at this point I only, I know of two producers off the top of my head that are still producing sunflowers. The rest of folks are [00:39:00] still they’ve moved to that safflower. Component for the rotation and so yeah, the resilience of our producers and the their ability to adapt to these and their ability to make these business decisions.

That allow them to remain in business year after year. That was, on the margins that they’re getting because once again, dry land farming is very thin margins. If you look at the price of wheat right now, which I haven’t looked for a little while our elevators go by the a hundred weights.

So I think it was. Right around $6 and 80 cents, a hundred weight which translates to about three something a bushel, which uh, if you look at that, that’s about the same price that. Farmers were being paid for their crops in the sixties. And that’s conventional, of course, your certified organic production, that’s going to add a lot of value to that crop.

And that’s the reason a lot of folks have moved in [00:40:00] that direction. But yeah, once again, working on really thin margins and it doesn’t take a lot of impact to throw your business into a loss and. The the business acumen of a lot of our producers is it’s impressive to say the least.

Thomas Plank: Gus, thank you so much for your time today. It was great having you on the show, and it was great to hear all of this new knowledge to me at least about dry land farming.

Gus Westerman: Excellent. No, it was once again, a pleasure to be on here with you and no, just very exciting. It was great to meet you, Thomas.

Credits

Thanks again to Gus Westerman for joining us today.

On Land is a production of Western Landowners Alliance, a West-wide organization of landowners, natural resource managers and partners dedicated to keeping working lands whole and healthy for the benefit of people and wildlife. This episode was produced by me Thomas Plank, with support from Zach Altman, Louis Wertz and the Walton Family Foundation. Thank you.

Our new theme song is ‘Moon over Montana,’ performed by our friend Sterling Drake.

If you enjoyed this episode, share it with a friend, leave a review wherever you get your podcasts. Your support helps us amplify the voices of stewardship in the American West. Thanks for being here. We’ll see you next time.