“We have three basic goals, the primary one being that we must have an economically sustainable operation. If our operation can’t pay for itself, we can’t achieve the other two goals,” Glenn Elzinga explains.

The Elzingas’ second goal is an ecological one: to continually improve the condition of upland and especially riparian habitats on the lands they steward for a variety of species, including wolves, sage grouse, salmon, bull trout and threatened and endangered plants. Through grazing management, the Elzingas have allowed the riparian areas to reboot and are now seeing species of willow and herbaceous plants once thought extirpated.

The third goal has to do with people. As Elzinga explains, “We need to train a new generation in the science and art of stewarding these lands in a responsible yet profitable manner. Our interns quickly learn that these cattle are a million-dollar investment entrusted to their care, that this job requires focus and commitment.”

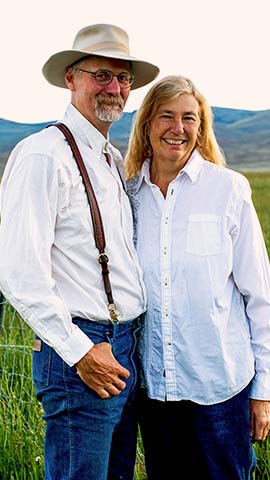

After years working for the federal government as a professional forester (Glenn) and plant ecologist (Caryl), the Elzingas shifted gears to cattle ranching in Idaho’s Pahsimeroi Valley. Part of their program includes training interns in low-stress livestock handling to protect yearling cattle from wolf predation. “We generally hire interns with a clean slate; that is, few preconceived ideas about livestock handling,” Glenn Elzinga said. The Elzingas select five or six interns out of 50-60 applicants each year.

In summer, after wintering and calving in the valley, the Elzingas head to the high country on the Alderspring Ranch in central Idaho. Glenn and Caryl Elzinga graze yearling cattle among wolves, lions and black bears. “We need to train a new generation in the science and art of stewarding these lands in a responsible yet profitable manner,” said Glenn Elzinga. “These cattle are moved frequently as calves among electrified paddocks, so they have frequent low-stress contact with humans, horses and dogs by the time we trail to the mountain summer pastures.” Using pressure-release, low-stress handling practices along the way, this mixed bunch of 600 – 1,200 pound yearling heifers and steers learn the safety of the herd. It takes about a month before the group truly functions as a herd, “or, as Bud Williams says, ‘make the cattle want to do what you need them to do.’”

Riders attend the herd constantly, camping alongside them at night. The herd beds in temporary, electrified night-penning enclosures that are moved periodically throughout the summer. Cattle are penned at night and grazed across different grazing circuits each day. “In order to be profitable, these cattle need to average two pounds of weight gain per day through the summer, so they need to get their fill of fresh feed every day.” By managing in this way, the cattle gain better, and “they feel safe in the herd, without stress from herders or predators.” The Elzingas have also found that keeping the herd moving and on fresh feed reduces death loss from predators and poisonous plants to zero.

The Elzingas have also found that keeping the herd moving and on fresh feed reduces death loss from predators and poisonous plants to zero.

One advantage to using yearlings is their trainability. For example, with constant and consistent herding, they quickly learn that riparian areas are not a food source. “Before long, the yearlings don’t even try to feed; they just get a drink and move back upslope.” The Elzingas observe that riparian areas respond positively to this management. “It’s as if they’ve rebooted. We’re seeing species of willows and other plants we thought were long gone.”

There are generally two to three riders within 300 feet of the herd at all times, and they have even learned to work the cattle in the timber. “I don’t want to avoid the timber. There are times when it is good forage, and it is benefitted by periodic grazing,” Elzinga says. He has developed a systematic way to graze cattle in forested areas, even though herders can only see a portion of the herd at any given time. He explained, “The three riders are arranged around the herd at roughly 120 degree intervals. We all know the direction we’re moving, and each rider works back and forth along their respective perimeter until they hear or see the adjacent rider. We talk, call or sing so the other riders and cattle know our whereabouts. This effectively keeps the herd bunched, grazing and moving slowly through the timber as a unit.”

This post originally appeared as a case study in WLA’s Reducing Conflict with Grizzly Bears, Wolves and Elk: A Western landowners’ guide.