Kurt. A Human of the Working Wild

Humans of the Working Wild is a collection of stories from people in the West who are living, recreating and working with and among wildlife on working lands, lightly edited from their own spoken words. Humans of the Working Wild speaks across the rural-urban divide, sharing common human experiences on working lands that provide important wildlife habitat. We are inspired by one of the most successful profile series of all time, Humans of New York.

“I come from a homesteading, agricultural family in the Midwest: five generations of agricultural people who farmed. My dad farmed. He passed away in 2008 and I had planned on being a farmer and raising livestock. He had a small cow-calf operation and I planned on doing that. That part of my life didn’t really work out the way I thought it would. It left a big hole in me. So I started looking around and the wildlife part of it and the agricultural part of it came together in coexistence work for me. It gave me a window to get back into the agricultural side of things, it was an opportunity I didn’t really have.

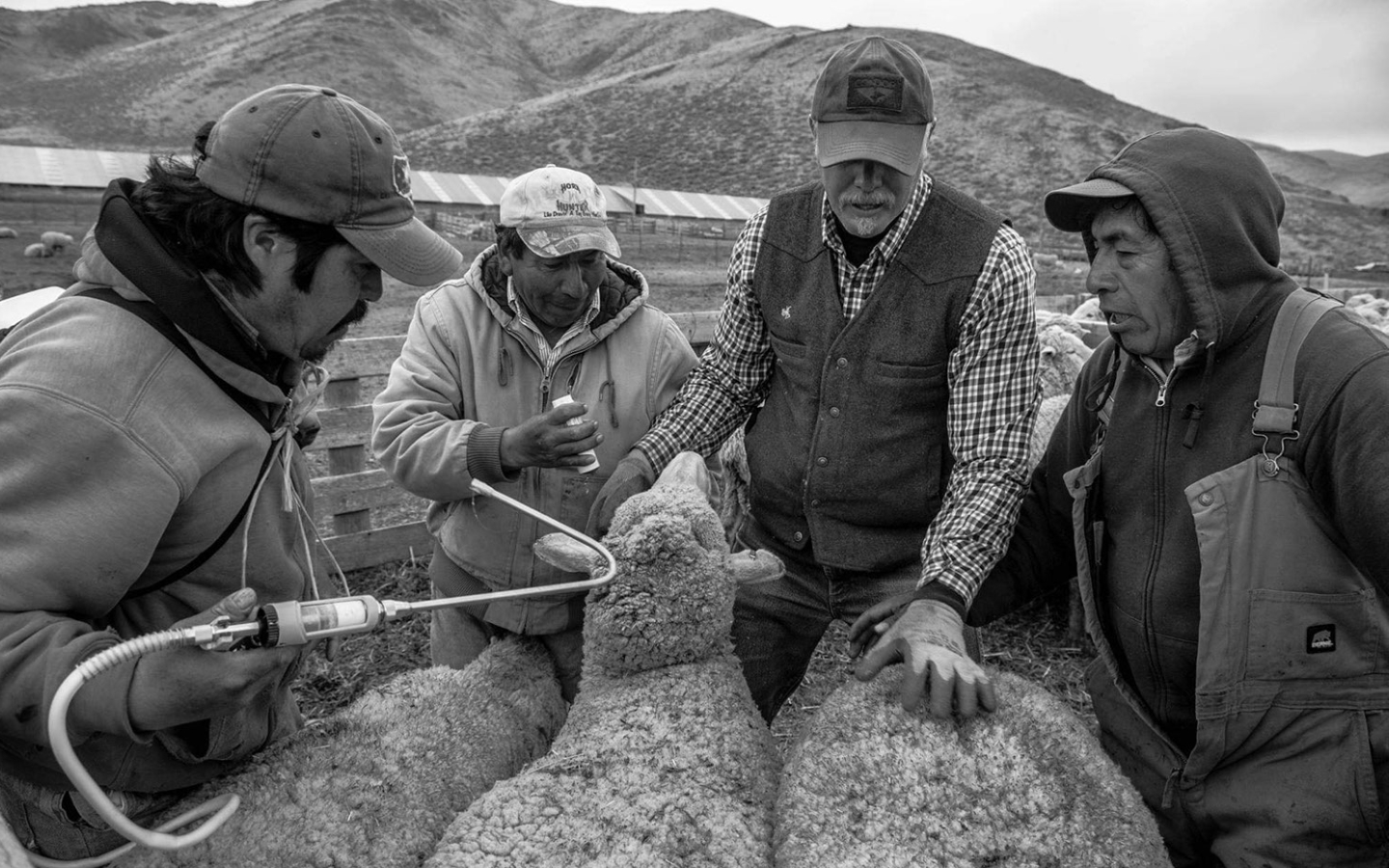

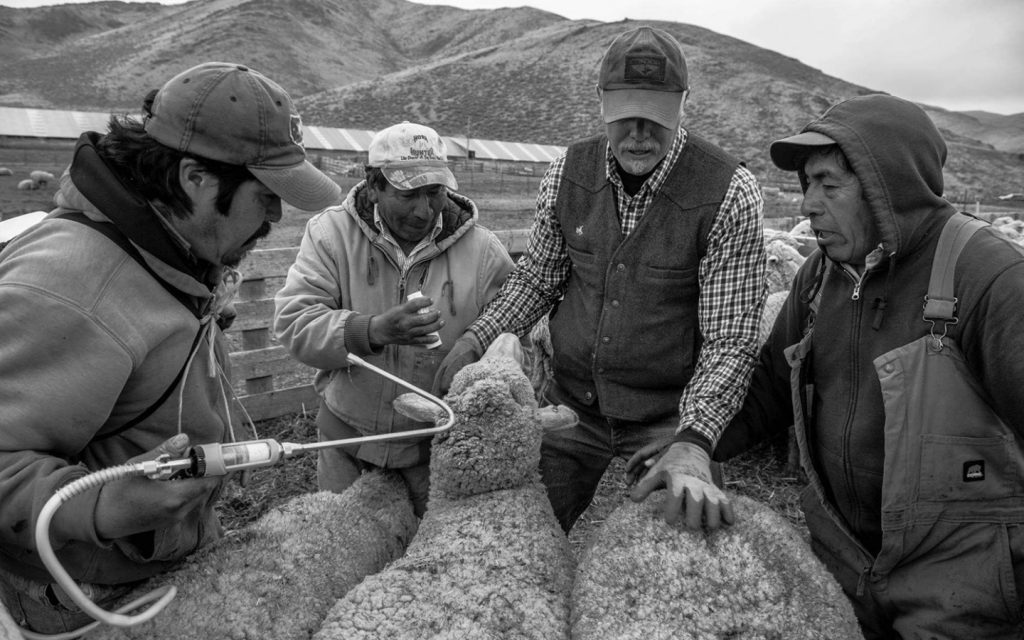

“I was working for a municipality as a water operator, and so I just didn’t really have that avenue back to that lifestyle and some of the things I really enjoyed. So I started working with the Wood River Wolf Project and Lava Lake Lamb…. I started going out there and working lambs, paint branding and loading lambs to ship for market. I really enjoyed that kind of work and getting back to that lifestyle. It filled a little niche for me. That was a good meld between the coexistence and the agricultural parts.

“For me personally, I have such a love of agriculture and wildlife that it’s just a good mix of the two things working in coexistence. Some people think they’re the icons of the West – when you think about big open lands with ranches and grizzly bears and wolves, they’re all icons of the West. I would like to see all of that continue. It’s hard to find the middle ground. Getting people to sit down and maybe find commonalities, it’s at least a step in the right direction. And I think everybody or most people love what they think the West is, the public lands and the wildlife, the large carnivores and all of it.

“I have almost exclusively focused on the field stuff, the wildlife part of it, the non-lethal tools, and stayed out of the human side of things. Maybe that’s more of my nature. I’m not a super social person anyway, so my preference is to work with the sheep and the wildlife. I understand that part of it. They don’t have any social expectations. Wildlife do what wildlife do. If I do the right things, use the right tools, they’re going to behave this way. For me, that makes it easy. Maybe I’m spoiled: I’ve stayed out of the human side of things.

“[Humans] have so much baggage that wolves don’t have. They’re working with instinct, basic needs and drivers. We humans have so much other stuff that’s involved. I think I appreciate the simplicity of wildlife. It doesn’t work every single time, but it’s fairly predictable that if we do the right things with conflict mitigation tools, then the wolves will do what they’re going to do.

[Humans] have so much baggage that wolves don’t have. They’re working with instinct, basic needs and drivers. We humans have so much other stuff that’s involved.

Kurt.

“I’m a big believer in more natural, balanced management. And large carnivores can be a part of that. If you have a stable wolf pack that you’re coexisting with, with minimal use of conflict mitigation tools, they’re eating elk, they’re moving elk. Oftentimes elk are predating hayfields and haystacks that cost way more money than depredations. This spring, we’ve seen wolf presence there and lower coyote numbers and coyotes depredate far more lambs than wolves do. There’s a balance there, trying to find the right balance with conservation and wildlife management is pretty tricky. But I see a great deal of value in a more natural, balanced management of wildlife. [Wolves] can be useful tools. I mean, if we get past all the political stuff and just look at it as a management tool, a pack of wolves are pretty handy if you have elk coming in and depredating alfalfa or haystacks, and coyotes…. We certainly saw fewer coyotes this spring and we have known wolf presence out there. I feel like the two are related. If you can figure out a way to kind of navigate the middle and more natural management, even using wildlife to your benefit, it just works better, trying to go with the natural order rather than trying to change it or fight it.

“I know oftentimes it’s political or ideological, just different viewpoints from different types of people. For me, large carnivore coexistence is not a political or an ideological thing. It’s wildlife management, it’s a management tool. I try to leave all the other things out of it and look at it as just black and white management, wildlife management or ranch management.

“I don’t know if everybody looks at it that way, but having come from five generations of people that farm and live that lifestyle, I know [agriculture] has a great deal of value. I see that in these big family-owned ranches that are passed down from generation to generation. It’s about the stewardship of the land and I think those are all very valuable things…. It’s all connected. Especially in the West, where you have these privately owned ranches that are in wild places and butt up against public lands, it’s all connected.

“I live in a place that is pretty wild, and I live here because of that. I’m not sure I’d want to live anywhere that didn’t have wilderness and wolves and bears and backcountry. I just need to get out and get into some of that country and it’s good for my soul and keeps me in the center. So I guess that’s what [living the way I do] means to me. The ability to get into the wild country completely…. Just knowing that it’s out there is comforting, especially when a lot of those places are getting smaller and smaller and harder to find. It’s a combination of those things, the feeling and also the rationalization that it’s that it’s out there and available.

I’m not sure I’d want to live anywhere that didn’t have wilderness and wolves and bears and backcountry. I just need to get out and get into some of that country and it’s good for my soul and keeps me in the center.

Kurt.

“The dynamics are changing. The way things currently are, there seems to be such a big division over everything these days, and wildlife management is the same. But I would hope that maybe there was a way to be less partisan about the natural world and wilderness and conservation, the kind of things that I think both groups of people believe in and want. It’s just a matter of how we get there where we seem to be so divided.

“I just hope people continue to come together with shared values for wilderness and wildlife and we’re able to work together to continue that into the future. I’d like to see sheep grazing in the valley peacefully with people riding mountain bikes…. I think we’re moving in that direction. I mean, you look over the last year or so, how many more people have done that kind of thing, gotten outdoors and into some of the wilderness areas. It goes back to these big sprawling ranches. You just want them to be successful because if they aren’t, they’re going to put a subdivision on some of that ground that is up against wilderness areas and forest service land. People are building and building, building in winter range. There’s a value in those properties being managed by a family supporting wildlife. Those properties are a buffer for the really wild places and help keep some of our humanity.”