The View from Here

I am conflicted about scenery. ‘The view’ complicates life, and conservation, in Missoula, Montana’s North Hills, where I grew up. I returned to Missoula in 2005 after 25 years away. I was contracted by a local land trust to help with open space planning for the county. My mom still raised cattle on our family ranch, but when Missoulians looked at the ranch from town, they didn’t see the people who lived there and tended it. That’s changing, but can shifting attitudes keep up with the pace of development?

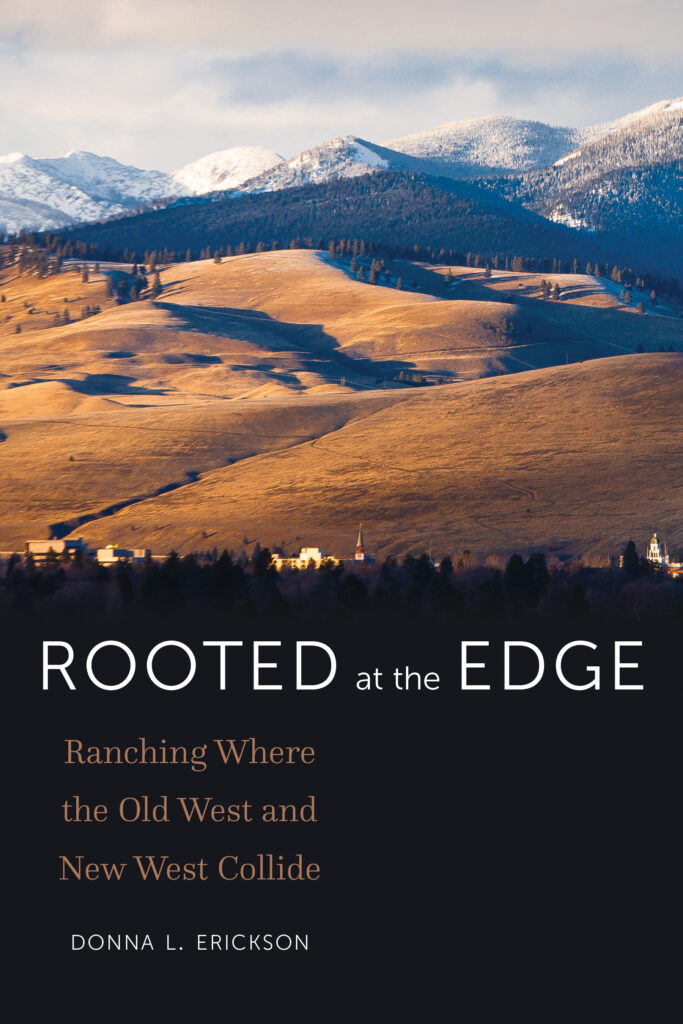

Adapted from Rooted at the Edge: Where the Old West and New West Collide by Donna L. Erickson by permission of the University of Nebraska Press and imprint Bison Books. © 2025 by Donna L. Erickson. Available wherever books are sold or from the Univ. of Nebraska Press 800.848.6224 and at nebraskapress.unl.edu.

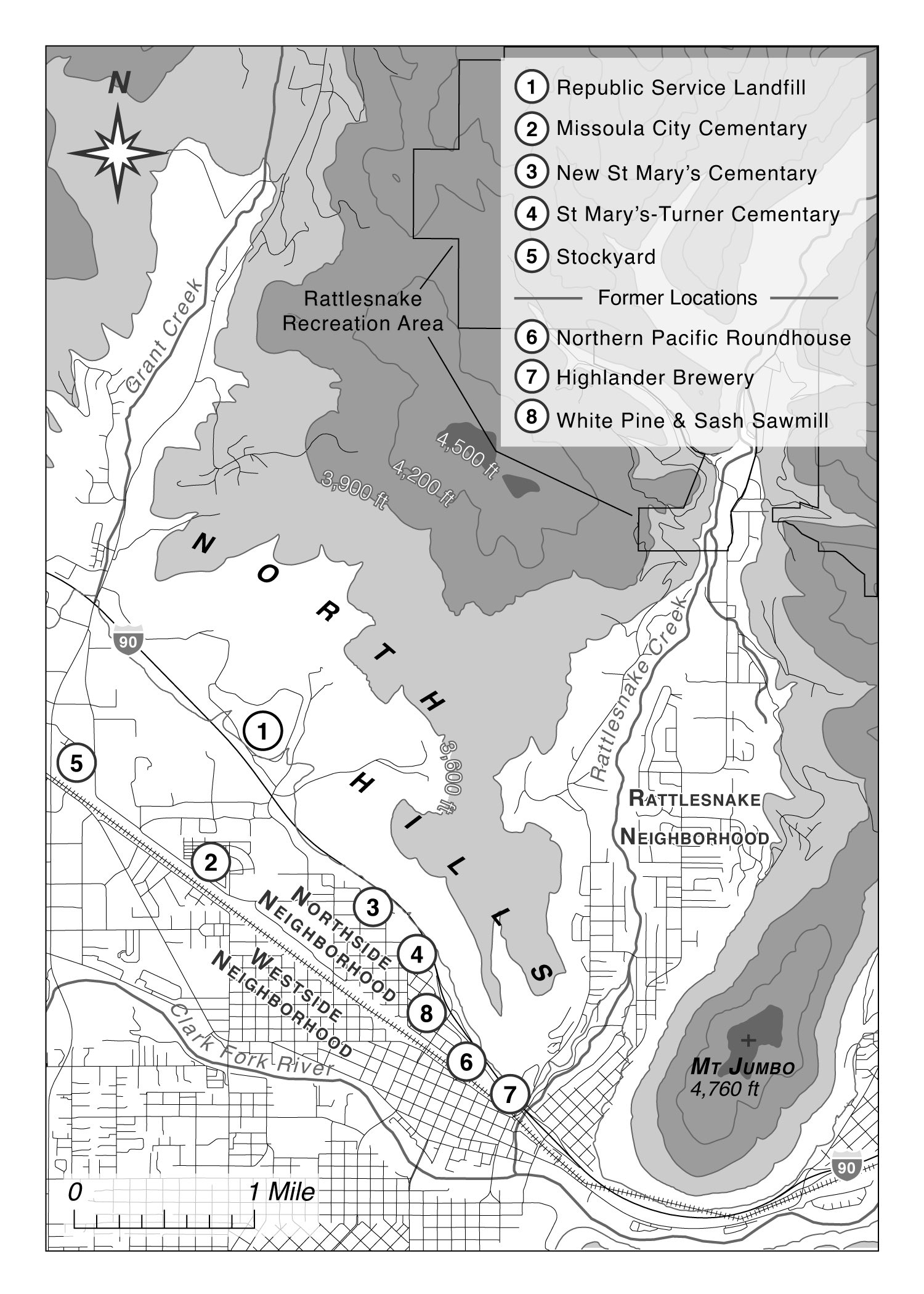

During the years I lived outside Montana, I could easily explain where I was from by mentioning an image from a popular movie. In the opening credits of A River Runs Through It, the camera pans across the Missoula valley from the south for a couple of seconds, revealing the 1950s-era town, the hills north of Missoula, and the Rattlesnake Mountains beyond. Missoula sits in the hub of five valleys and the native trade routes that fan out from them. The rivers create a valley pattern—Bitterroot, Blackfoot, Upper Clark Fork, Lower Clark Fork and Mission. The town nestles between mountain ranges west of the Continental Divide.

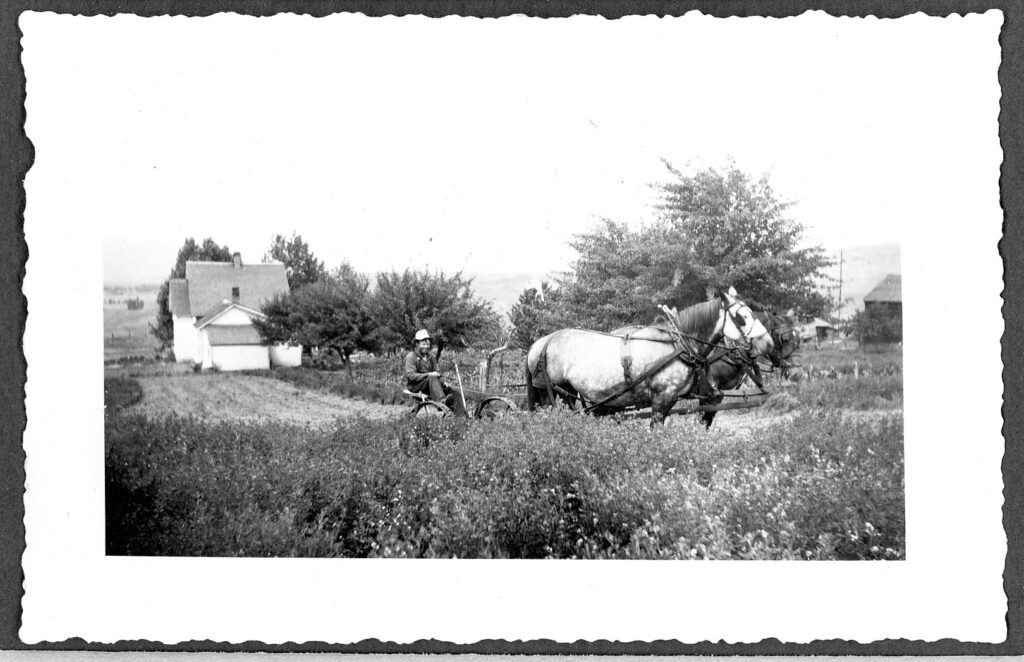

The movie viewer can glimpse the timbered ridge line of Skyline Ranch in the North Hills, my family’s land, bridging town and mountains. Three ranches form my North Hills mental map, a neighborhood of pioneering families who settled here in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The land is central to the identity of five generations of North Hills families, who have faced constant battles with scarce water, abundant rocks, fire danger, drifted roads, invasive weeds, trespassing urban neighbors, steep slopes, and marauding dogs. Although the North Hills are separated from town—higher, dryer, more exposed—they have always been linked to forces starting in town. For earlier generations, that force was providing food and employment for townsfolk. Along the way, the North Hills became a place to dump garbage. Now it is in demand for its scenery, wildlife habitat, and hiking trails. The dichotomy between practical and amenity values sets up tensions affecting how the North Hills, and edge places like it, will be valued in the future. While the hills’ beauty is important for my attachment to the place, scenery represents the gulf separating practical rural landowners from their city neighbors.

People want open space, seeking something lost in an urban environment. But open space is an elusive concept on its own. I’ve spent much of my professional life exploring its meanings, methods, and outcomes.

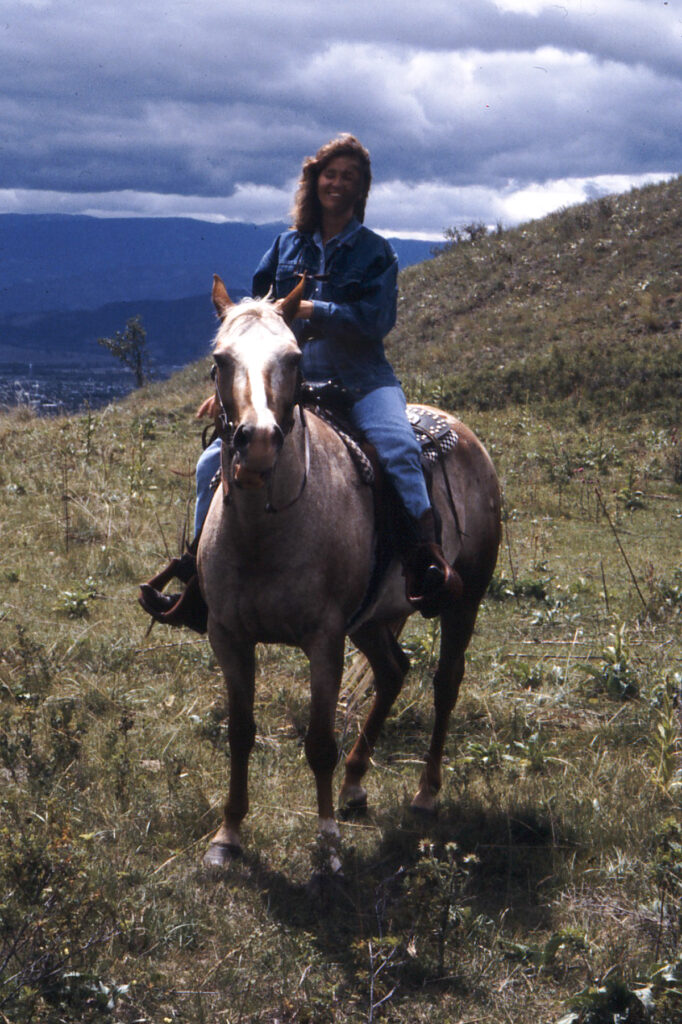

My family appreciates the views—both out from and toward the North Hills. For me, the visual sense is especially keen since, as a landscape architect, I learned to appreciate and analyze the components of aesthetic scenes—line, form, texture, color. In recent years we have gone to the highest points of the ranch not to chase cattle or check fences but to enjoy the view. It is a deeply held tradition. Just as some people always take visitors to a special museum or natural area, we take them to what we call “The Top.” Since the 1960s we have watched as houses crept up the South Hills across the Missoula valley, where their occupants enjoy spectacular views toward the North Hills and the Rattlesnake Wilderness. We decry neighbors who build on nearby ridge tops so they get spectacular views 24-7. People of earlier eras knew better than to build atop ridges, with the extra expense, wind exposure, and environmental disturbance from road building and other infrastructure.

From a distance the North Hills appear serene and static. They form a calm buffer between people strolling along Missoula’s Higgins Avenue shops and mountain lions prowling the Rattlesnake Wilderness. In the early years of World War II, Fort Missoula on the city’s south side became one of many internment camps holding people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens. Despite the tragic violation of American civil liberties, detainees called the camp Bella Vista—Beautiful View. Their main view from the fort was toward the North Hills and the mountains beyond.

The North Hills area is a pivot point, an edge, a place where the city and wilderness nearly collide and where small areas of farm and ranch land separate them. Edges are often contested. The North Hills is part of a larger edge, or ecotone, defined in ecology as a transitional zone between two communities with distinct plant communities and physical characteristics, in this case forest and valley lakebed. The North Hills’ bluebunch wheatgrass and fescue grassland are edge species, transitional between the lower mixed grass prairie and the montane/subalpine grasslands higher in the forest habitats. The influence of two bordering communities is known as the edge effect; many plant and animal species thrive only in these edges. Missoulians thrive there too.

The North Hills area is a pivot point, an edge, a place where the city and wilderness nearly collide and where small areas of farm and ranch land separate them. Edges are often contested.

People are drawn to edge places, whether it’s a riverbank, meadow perimeter, or hilly overlook. The North Hills have been a popular walking destination over the last thirty years. People can clamber up from Missoula’s flat urban neighborhoods and enjoy spectacular views toward the mountains, sunsets, and the city itself. Over the last ten years, use has intensified since hikers have an uninterrupted route all the way from the Clark Fork River to the Rattlesnake Wilderness. The hiking craze began in the 1960s and has steadily grown. Numbers of trail users are not going to diminish.

People want open space, seeking something lost in an urban environment. But open space is an elusive concept on its own. I’ve spent much of my professional life exploring its meanings, methods, and outcomes. For planners, open-space protection aims to preserve views, agricultural land, recreation spaces, water resources, wildlife habitat, and non-motorized transportation corridors. Those goals can be at odds with one another, creating tensions and challenges.

Starting in the 1970s, the City of Missoula began to actively preserve open space, particularly on Mount Jumbo and Mount Sentinel on the city’s eastern edge, and land along the Clark Fork River, all then in private hands. A 1980 report by a Regional/Urban Design Assistance Team working with Missoula recommended that “no development should be allowed to mar the grassed hillsides that surround the valley in any way.” The city passed bond measures to raise funds for open-space acquisitions and conservation easements in 1980 and 1995, in part for scenic protection. In 1980, the focus was on acquiring land along the Clark Fork River and protecting Missoula’s iconic hillsides. The 1980 $500,000 bond purchased land along the river, as well as a conservation easement on the part of Mount Sentinel facing Missoula, creating over 3000 acres of public open space. The $5 million 1995 bond gave Missoula nearly all of Mount Jumbo, Mount Sentinel, Waterworks Hill, and linear greenways in the city. It converted the Randolph homestead in the North Hills to public ownership. Missoula’s open-space bond measures were precedent-setting, inspiring other mid-sized western cities to garner public funding for open and scenic lands.

“No development should be allowed to mar the grassed hillsides that surround the valley in any way.”

– 1980 Regional/Urban Design Assistance Team report

When the city developed its 1995 open-space plan in the lead-up to the bond measure, it identified eight cornerstones surrounding the city— Mount Jumbo, Mount Sentinel, Fort Missoula, the South Hills, the North Hills, the Clark Fork and Bitterroot River corridors, recreational playing fields, and community trails. The city described these cornerstones as “giving shape to the open-space and built environment systems, making important open-space connections, serving as special local landmarks, exemplifying important natural features, offering exceptional beauty, and providing many recreational opportunities.” The city now owns and manages 4200 acres of open-space conservation lands and 59 miles of trails.

In 2005 and 2006, after my move back to Missoula, Five Valleys Land Trust contracted with me to manage and facilitate a citizen-driven Missoula County open-space working group. I helped the group propose a range of tools the county commissioners might use to help private landowners interested in voluntary land conservation. I traveled to all corners of the county, meeting with rural landowners. In 2006 the City of Missoula sought public input as it updated its open-space plan prior to the open-space bond vote. I participated in a public meeting of about 100 people sponsored by the planning department. A planner showed slides describing lands at Missoula’s periphery that were either protected or threatened. She showed North Hills views from multiple angles and in different seasons. One late fall image showed the North Hills from the city, with snow on Skyline Ranch’s highest hillsides and none on lower Randolph Hill, owned by the city. The speaker’s point was that the snow cover happened to delineate the line where protected met unprotected land. It was a clever illustration, but misleading. Although I understood the speaker’s point, I was glad that North Hills landowners were absent. This ‘protected’ distinction at the snow line would have been an affront to the work ranchers have done to keep their land intact and working. To them, “protected” would translate to public ownership, which they oppose. The brief moment epitomized the gap between urban and rural values at Missoula’s edge.

Although wildlife habitat and water protection drive North Hills conservation, the viewshed—a word not in North Hills ranchers’ vocabularies—is a primary motivation. Websters defines a viewshed as the natural environment visible from one or more viewing points. Urban planners map viewsheds for areas of particular scenic or historic value worthy of preservation from development. Valuing the North Hills for viewshed, which does not necessarily involve owners and residents, is the opposite of valuing it for its productive potential, for ‘what comes off the land,’ as my mom would say.

Valuing the North Hills for viewshed, which does not necessarily involve owners and residents, is the opposite of valuing it for its productive potential, for ‘what comes off the land,’ as my mom would say.

The project led to a joint city-county $10 million open-space bond measure in 2006. It focused on four main goals: water quality and wildlife habitat; working farms and ranches; open space and scenic landscapes; and trails and river access. Voters passed the most recent 2018 bond measure with similar goals. Many taxpayers paying for open-space bond programs resist spending money to protect land on which they cannot walk, hunt, and/or bike. They feel that Missoulians should have access to land conserved with public money. However, in the 2006 and 2018 bond measures, voters approved funding for open-space conservation projects without public access. As people learned more about open space’s intrinsic values, many of them supported funding to preserve non-recreational uses. More taxpayers now value keeping land working and protected from development, even if they are not free to walk on it. Since 2006 Missoula County has funded conservation easements on over 15,000 acres of land that have stayed in private ownership. These lands are open to the public only by invitation.

Many positive outcomes emerge from the community valuing its local open space as never before. Increasing interest in the North Hills brings resources, from open-space funding to volunteer forces, to educational opportunities. The increased attention and use, however, is also problematic when landowners feel alienated and beleaguered. Aesthetic considerations are central to trespassers who are not content to look at the North Hills, but rather wish to be there. This dichotomy is playing out not only for the North Hills but for rural land at the edges of many towns.

Modern ranchers’ motives are not typically aesthetic. Even though they care about the view, their concerns are about remaining economically viable and keeping land in good condition. My mother wrote about the ranch’s value as a community viewshed in a letter: “We have always felt there is a false collective mentality that they ‘own’ our place for their personal visual pleasure. ‘Visual Resources’ are the key words. We heard that many times in the city/county planning process.” She went on to explain that she did not plan to develop the ranch, but that development was a retirement ‘ace in the hole.’ Her letter outlined how an 80-acre section of the ranch had at one time been zoned for two dwellings per acre. She was embittered that she not only lost this liberal zoning, but a conservation strip was placed along the ranch’s eastern fence line to further assure that an access road, sewer, or water would never cross from the neighboring Rattlesnake Valley to the ranch.

A recent North Hills conservation easement further illustrates the complexities of open-space protection. Republic Services bought a North Hills ranch, intending to expand Missoula’s landfill. The new owner placed a conservation easement on 304 acres adjoining Skyline Ranch’s western side. A local land trust holds the easement, and the owner was compensated from 2006 open-space bond funding. As with any conservation easement, the deed restricts the amount and location of any future development, if any. This restriction holds regardless of who owns the land in the future. This conserved property is mainly open, crossed by woody draws that provide wildlife and bird habitat and contain large ponderosa pines and intermittent springs. According to the City, “the property is visible from the large majority of all neighborhoods in Missoula. Besides the tremendous scenic viewshed value, the conservation easement will protect elk winter range, wildlife habitat and bird nesting and feeding habitat for many species, and over 120 acres of Soils of Local Importance.” Note that this description does not include agriculture. The owner also committed to work with the city in granting a future public trail easement across the property.

The ranchers hanging on in the North Hills wonder: How will anyone use the conserved land, if at all? Is it still ranch land and who will try to make a living on it? Will anyone maintain fences? Will public access bring even more pressures to our fence lines? These questions help me understand that the forces which affected my grandfather on Skyline Ranch differ from the ones my mom faces. She worries about high land values (which may translate to exorbitant estate taxes at her passing). People pressure her to consider developing part of her land while others pressure her to conserve it for elk habitat, scenic views, and recreation. Her father had none of those worries.

The semantics of land conservation, preservation, and protection complicate efforts to guide landscape change. Land conservation traditionally protects natural resources from damage, which can involve directing development. Land preservation typically aims to limit human impacts and forestall development. The two terms are often tossed around interchangeably. The dichotomy of ‘protected’ versus ‘unprotected’ usually refers to the risk of housing development.

In the North Hills, conservation and preservation goals are compounded by protecting the view north from Missoula, by the desire for public trail access, and by historic preservation aims. How can we develop in ways that preserve views of the uplands? How can we compensate landowners who keep these lands open and working, encouraging wildlife habitat, water quality, and views? Volumes have been written on the ways local governments have tried to address farmland protection through regulation and incentives. For Missoula County, the conservation easement is one of the tools available to accomplish these diverse goals and the county has used it wisely.

I am content that much of the surrounding land is conserved, pleased to know that few trophy homes will sprout up as neighbors. My mom is less optimistic, feeling caught in the bullseye. She thinks of the surrounding conservation pattern as limiting her options, pressuring her to provide her land for the public good.

Of Skyline Ranch’s six miles of perimeter fences, over five miles of it separate the ranch from conserved lands—either in public or nonprofit ownership and with or without conservation easements. I am content that much of the surrounding land is conserved, pleased to know that few trophy homes will sprout up as neighbors. My mom is less optimistic, feeling caught in the bullseye. She thinks of the surrounding conservation pattern as limiting her options, pressuring her to provide her land for the public good. While I understand her reservations, I want what’s best for these rolling hills. I want to find solutions that meld productive use of the land, prevent development, and protect views.