Indigenous leaders urge California to rethink its relationship with fire

It’s a hot day in mid-August in Northern California, not too far from the Oregon border. Smoke rises gently from the fire pit, curling into the late-summer sky as children circle close, carrying small bundles of plants. Their hands move with purpose as they place their bundles into the fire. Around them, elders watch quietly, teaching through presence as much as words.

Elizabeth Azzuz lives for moments like this.

“Fire is part of the people. It’s part of the land.”

– Elizabeth Azzuz

Cultural Burning

“Fire is part of the people. It’s part of the land. And so just that alone has just got me floating,” reflected Azzuz days later. “I was up for almost two days straight by the time I came out (of ceremony) yesterday and had been tending fire, tending family, cooking, working with all the people that were there, working through what was bothering them, what they needed. That all revolved around the fire pit.”

Azzuz is director of traditional fire at the Cultural Fire Management Council, a basket maker, an enrolled member of the Yurok Tribe and a descendant of the Karuk Tribe. “I was in ceremony teaching an entire younger generation how to tend a ceremonial fire, right down to a 4-year-old. It was really nice to see the joy in their eyes, knowing that the medicine they were putting into the fire was praying for their whole community.”

Along the Klamath and Trinity Rivers, fire has long been regarded as kin. For millennia, Indigenous communities have tended the land with cultural burning, using fire to guide and renew ecosystems. Yet only in the past decade has the state of California begun to recognize this practice as a tool for healing both land and people. “Tribes in Northern California are at the leading edge nationally of this conversation around revitalization of fire culture,” says Pete Caligiuri, Oregon forest strategy director at The Nature Conservancy.

Reclaiming Fire

Margo Robbins, co-founder and executive director of the Cultural Fire Management Council, describes the cultural or purposeful burning as similar in practice to prescribed burning, but fundamentally different from a cultural perspective.

“They are very similar. The difference is that cultural burning is done by the indigenous people from that place. For cultural purposes. So those purposes might be to restore the health and availability of traditional food sources, basket materials, [and] it can also include home protection.”

In the early 1900s, such burning was outlawed. Indigenous people risked jail or even bullets for tending flames as their ancestors had. Generations grew up without fire, the traditional knowledge fragmented, and ecosystems degraded.

Robbins and other members of the Yurok tribe have reclaimed their right to burn. Today, the Cultural Fire Management Council runs family burns on small plots around homes, as well as larger training exchanges known as TREX that draw participants from across the country. They have also been integral in the formation of the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network, which began ten years ago with three tribes and has expanded to 27. Robbins says they receive regular requests to expand internationally.

“What good does it do to restore habitat if you burn when baby animals are in their dens?”

– Margo Robbins

Cultural cues guide burning how-tos

Azzuz frames the impact of fire on the things that she wants to protect. First and foremost is her people. After emerging from a six-day ceremony in triple-digit heat, she reflected on what kept people going.

“It was 106 degrees coming out of ceremony and everyone was still smiling,” she said. “Everybody was still smiling and happy and, proud of what they had accomplished.

That intimacy is what makes cultural burning distinct. The timing of burns is guided not only by weather but by ecological and cultural cues, such as the opening of oak leaves, the nesting season of animals, and the readiness of materials for weaving.

“What good does it do to restore habitat if you burn when baby animals are in their dens?” Robbins asked. “Even if the weather is perfect, we wait. Because everything is connected.”

Shifts in the legal landscape

California has begun to catch up. Recent laws recognize the authority of cultural fire practitioners as equivalent to federally certified burn bosses. The state has also created an insurance fund to cover cultural and prescribed fire, addressing a major obstacle for communities seeking to put fire back on the ground.

These are historic shifts, Robbins noted. “We went from being shot for trying to take care of the land with fire to now, our skills are recognized and we have insurance.”

But challenges remain. On tribal trust lands, federal bureaucracy can delay burn permits for years. Liability concerns make landowners hesitant. And the accelerating climate crisis makes the work more fraught, and more urgent.

“There’s just something to learn every day, every second, every moment, you know, and getting it out there to the people, hitting the right minds.” says Azzuz.

“There’s just something to learn every day, every second, every moment, you know, and getting it out there to the people, hitting the right minds.”

– Elizabeth Azzuz

Fire for the Future

For Azzuz and Robbins, that teaching is happening now, child by child, family by family.

Up and down the Klamath and Trinity Rivers “Every village that has gone into ceremony has gone into ceremony with fire and water,” Azzuz says. “There are so many things that revolve around fire for us. And I can’t even express how happy I am… to have all the people come to me while I’m in ceremony and say, how do we connect with your organization? How do we support you? How do we bring you to our territory?”

As California braces each summer for another wildfire season, Robbins and Azzuz continue to argue for a different vision, one where fire is not the destroyer but the healer.

“We’re all interconnected…meet the people around you and build a connection with them so that you care about them when something is happening. It’s easy when we’re having a disaster to think only in your little hive, but if that hive spreads out and starts taking care of each other…” says Azzuz. The next steps are clear: “We need to go from there and make it real for the outside world, so they understand how important this is. To all of us.”

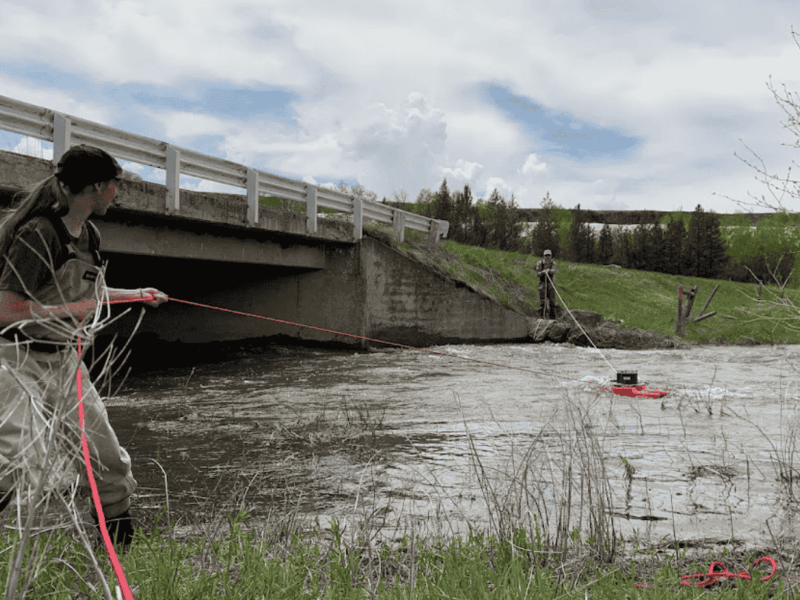

All photos courtesy of the Cultural Fire Management Council. Photographed by Killiii Yuyan.