Surface water conservation programs: What are they, and are they working?

In the sixth and final installment of our spring 2025 Water Webinar series, we explored one of the most complex topics in western water: temporary, voluntary, compensated conservation programs. The webinar examined the realities these programs; how producers utilize them, some of their shortcomings, including cost and potential permanent removal of irrigated farmland, and what producers can do to engage more specifically on water issues for the benefit of agriculture, land health and rural community.

We were joined by Mike Higuera, agricultural operations manager at Western States Ranch, an experimental agricultural operation run by Conscience Bay; Anne Castle, longtime Colorado River Basin water expert and senior fellow at the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment at the University of Colorado Law School; and Raquel Flinker, the Colorado River District’s director of interstate and regional water resources.

WATCH

What are compensated water conservation programs?

Castle sensibly kicked off the webinar by providing an overview of what a compensated water conservation program is. She utilized an example from the Upper Colorado River Basin, the System Conservation Pilot Program, or SCPP, to highlight the complexities of compensated water conservation programs.

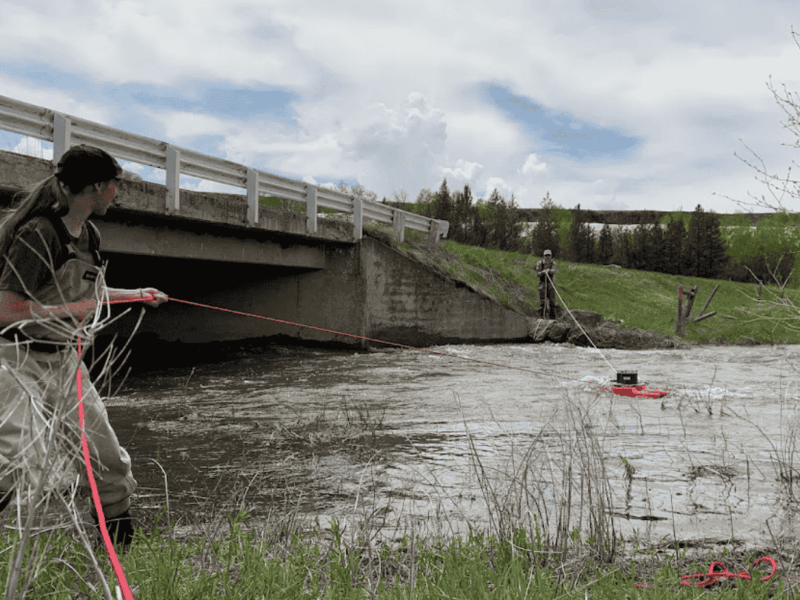

Demand management programs are compensated, temporary, and voluntary reductions of consumptive water use. Reductions in water use for agricultural purposes can take a number of forms, including fallowing fields, deficit irrigation, irrigation efficiency projects, switching to lower water use crops or decreasing water storage. As Castle shared, a prime example of this kind of program is the SCPP, a pilot program which ran in the Upper Colorado River Basin from 2015-2018 funded by state and federal sources, and 2023-2024 with funds from the Inflation Reduction Act. A bill has been introduced in Congress to reauthorize the program, but its fate is still up in the air. The SCPP paid between $200 and $650 per acre foot of water conserved in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming in 2023 and from $300-$509 in 2024.

SCPP project administrators reviewed proposed water conservation projects considering a number of factors:

- Is there a history of recent consumptive use?

- Will the water get where it needs to go?

- Is there a need for shepherding and can it be shepherded?

- How much water will be saved?

- How easy is it to verify and account for the saved water?

- Are there multiple benefits for saving this water?

For program participants (water users), those questions and considerations were different:

- What are the economic realities of being compensated for reducing water use?

- How much administrative hassle is there?

- What will the soil/land look like if not watered and will there be long-term effects?

- What happens to the water being saved?

- What are the benefits of the program to Upper Basin users broadly?

- What if conserved water is used by other water users before it reaches its intended destination?

- Do Lower Basin water users get to use more water because of conservation in the Upper Basin?

These specific questions were focused on the SCPP, but they point to larger questions about compensated water conservation programs more broadly.

Why these programs matter now

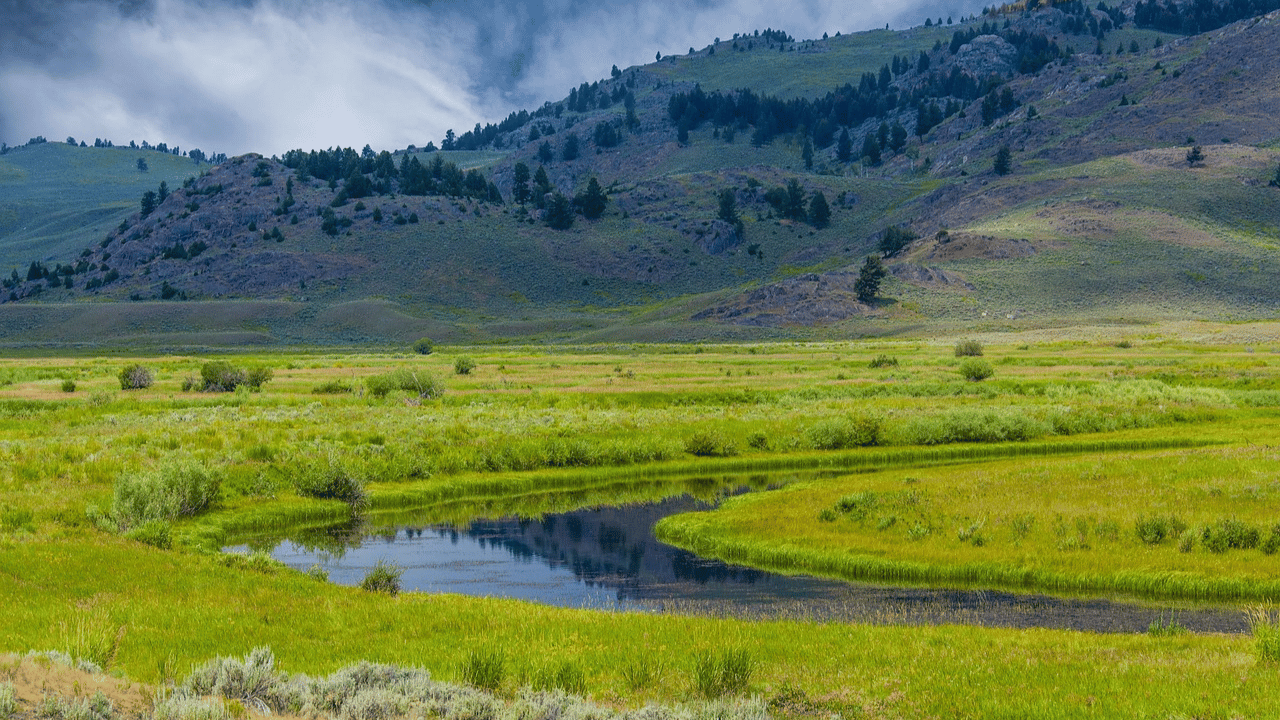

Flinker discussed why these programs continue to come up, and why water users within the Colorado River District are engaged with how they are designed. The Colorado River Basin is facing a long-term water deficit. Both Castle and Flinker remarked on the clear relationship between rising temperatures and reductions in streamflow—research shows that for every one-degree Fahrenheit the average temperature rises, flows drop by 4-7%. Natural flows in the Colorado River have decreased by approximately 20% since the turn of the century, which has led to shrinking storage in Lakes Mead and Powell.

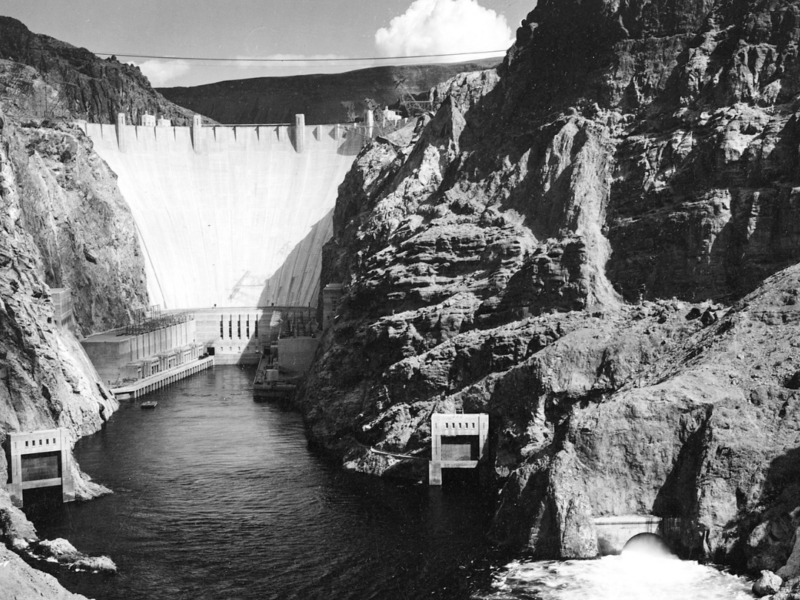

Regardless of the driver of change, demand for water in the Colorado River Basin is greater than the supply. By some estimates that shortfall may be in the millions of acre feet per year (one acre-foot of water supplies approximately two households with water for a year). At their root, compensated conservation programs are designed to shrink that gap.

A tool – but not a silver bullet

Overall, compensated water conservation programs may be ultimately play only a small part in solving the problems facing the Colorado River Basin. But for landowners, they can provide important compensation for economic loss from using less water and can help producers bridge from more water-intensive crops or practices to less water-intensive operations. For Higuera with Western States Ranches, these programs are the best alternative to “buy and dry,” the practice of buying farmland and its water rights, and then transferring that water to a municipal or industrial use that eliminates agriculture entirely. Buy and dry has significant impacts on communities, wildlife and agriculture. Compensated conservation programs can make up for water supply deficits that result in reduced agricultural production or offset the costs of changing practices or updating infrastructure. Higuera said that Western States has adjusted its operations so that the water lease payments are functionally insurance against bad water years when they have to operate at a deficit.

Balancing tradeoffs

Flinker discussed the tradeoffs of compensated water conservation programs. She referred to CRD’s recommendations regarding sideboards for the SCPP. And she highlighted that producers and rural communities recognize that voluntary and compensated programs are obviously preferable to uncompensated mandatory curtailment of water use, which is a major concern. Flinker noted that these programs allow the Upper Basin to be a part of the solution for the water deficit while also supporting farmers and ranchers in the region as they explore new drought-resilient practices.

Concern remains that conserved water is not being stored for the benefit of the Upper Basin or to rebuild long-term resilience but rather has essentially underwritten continued demand growth in the Lower Basin and Front Range of Colorado. Flinker also noted that there are significant concerns about the impacts of deficit irrigation or fallowing on soil health and long-term water storage in soils.

Compensated water reduction programs can also provide producers with the economic assistance necessary to test the impacts of deficit-irrigation, which may not always be negative. Higuera and Western States Ranches in partnership with Colorado State University utilized the SCPP in 2024 to examine the impacts of drought stress on grasses and potentially lead to improved root structure, increasing their drought tolerance. Western State Ranches is working to improve their understanding of reduced water use and drought on their agricultural operations so they can provide that knowledge to other producers working under similar drought conditions.

Opportunities for landowner-driven innovation

Compensated water conservation programs also come with very real economic concerns for landowners. Castle referred to a Lessons Learned document about SCPP that provides a more in-depth review of the strengths and weaknesses of the program. Often, for producers, the timing of the agreement is key. Agricultural producers need earlier application processes to be able to plan their inputs— the fall prior to the agreement is preferable for agricultural producers’ timelines. Additionally, fixed pricing provides economic predictability. Clarity regarding how applications are reviewed helps producers determine what kinds of projects are likely to be successful.

Just one tool in the toolbox

All participants agreed that programs like SCPP are not going to fully close the gap between supply and demand in the Colorado River Basin and should be thought of as only one tool in the toolbox for matching supply and demand during these times of increasing water scarcity. In the last 25 years, the Colorado River Basin’s hydrology (total water contained within the river’s flows) has been around 12 million-acre feet. Prior to 2000 the river averaged 15 million-acre feet per year. Flinker presented data on the amount of conserved water under the latest year that the SCPP operated. The program resulted in reduced consumption of around 100,000-acre feet, a fraction of the reduction needed to bring use into balance with available water.

Looking ahead

As scientists are warning that the Colorado River Basin may be headed for an average runoff of 10 million-acre feet, Castle noted that conservation programs do help close the gap between supply and demand, but their temporary nature means that once they end, the gap goes back to where it was before. According to Castle, the changing hydrology means it will eventually “become impossible to pay people long-term not to use water that is no longer there.” Thus, she contends, these temporary programs are best used, as Higuera and Western States are doing, to build bridges to more drought-resilient agricultural communities and healthy landscapes in what will be a more water-scarce basin for the foreseeable future.

Higuera noted that they have taken this approach, and focused on adapting their operation, not because of the temporary payments, but because he sees mandatory water cuts coming for agriculture. Nevertheless, within that change, he sees an opportunity for farmers, ranchers and others in agriculture to work together to craft creative solutions. Flinker also highlighted that getting involved with these programs can provide opportunities for positive change that keeps agriculture viable. However, if the programs are poorly designed or cumbersome to access, the advantages of adaptation are likely to bypass communities who are already hardest hit by water scarcity and where farming livelihoods are already marginal.