“Liquid” assets. Revenue “streams.” Water has a tendency to become a great metaphor in the world of finance. Its flexibility as a metaphor also flows into its fungibility as an asset.

Across the American West, “water banking” describes a number of different ways of protecting water for producers and communities. Idaho and Arizona have vastly different ways of banking water, and New Mexico’s Ogallala Water and Land Conservancy is on the bleeding edge of keeping water in the ground through conservation easements. Each “bank” is tailored to the needs of its constituents, and that tailoring offers food for thought on how conservation of water can take place in the future.

Standard Issue Banking

The state of Idaho has been running a water banking operation for nearly 50 years. First considered in the 1976 Idaho state water plan to deal with supply and demand problems, the water bank was designed to provide a market where willing buyers could rent out established water rights. Adopted in 1980, the bank is currently managed by Mary Condon, Idaho’s water supply bank coordinator, who is in charge of tracking and managing the bank.

“For groundwater rights, springs, surface water, if you need the place of use to change, that needs a permanent transfer through the [Idaho Water] Department. The bank offers a way to do this temporarily … it’s making the water supply available in the most efficient manner to those who need it for the ‘highest beneficial use,’” Condon said.

For anyone familiar with the legal framework of western water, “beneficial use” is one of the core tenets of water rights. Putting water to a beneficial use — for irrigation, stockwater, power generation, industrial uses, etc. — is how water right holders are able to keep using water year after year. If not fully used, they face the specter of losing their right. Idaho’s bank offers a solution and economic boon to those who might have too much water in a given year, and allows those who might need more water to access it with fewer barriers.

In Idaho’s system, water is banked in reservoirs, and producers rent water by the acre-foot. Seventy percent of all water rentals are for irrigation. The bank makes it easy for producers who might want to move a senior water right from one pivot to a pivot with a more junior water right: they just add water (and pay a 10% administrative fee the state requires from every water bank transaction).

“Producers need flexibility. They can use these acres this year, and these acres other years,” Condon said.

Credit Union

To the southeast of Boise, ID, an entirely different style of water banking is administered by one of the most drought-impacted states in the West. The Arizona Water Banking Authority, or AWBA, is decidedly not a market. Instead, as the authority’s manager, Rebecca Bernat, explains, they are responsible for keeping things underground in areas with heavy usage under control.

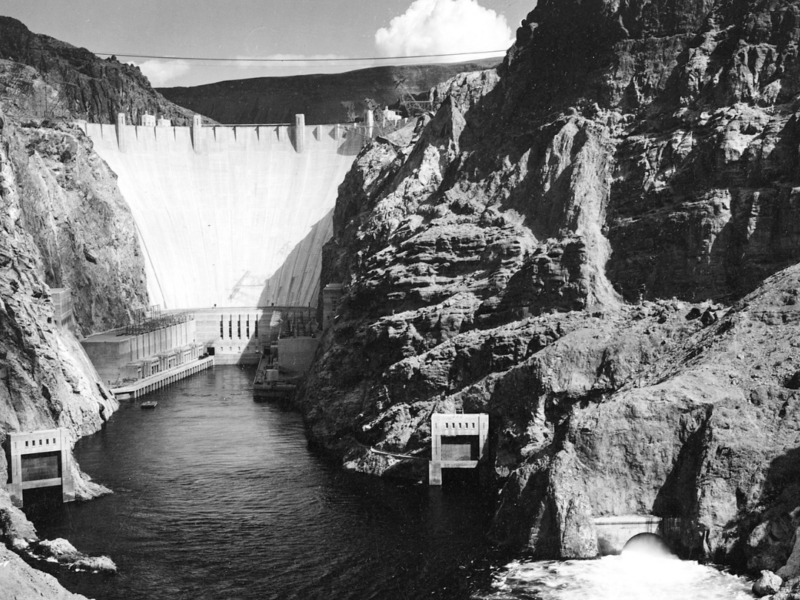

“Unlike other places that use water banking as a clearing house … we were created to hold and store unused portions of Colorado River water,” Bernat said.

Created in 1996, the AWBA was charged with storing the unused portion of Arizona’s annual Colorado River entitlement in Central and Southern Arizona. As time has gone by, the water bank has expanded its client list to include Mohave County, home of Lake Mead and the Grand Canyon, and the state of Nevada.

The state of Arizona is required by statute to have a recharge and recovery program responsible for tracking all water pumped into the ground and pumped out of the ground within the state’s seven Active Management Areas, or AMAs. Those districts cover 25% of Arizona. The AWBA keeps groundwater in three of those seven — Phoenix, Tucson and Pinal — because those are the AMAs that receive Colorado River water from the Central Arizona Project . The same groundwater regulation does not hold true for the rest of the state, including much of the land being used for agriculture which has led to battles in rural areas in recent years.

“The term ‘water banking’ can refer in other states to trade of water but in the literature, it is used to define aquifer recharge, groundwater recharge, aquifer storage and recover. It’s putting water underground and pumping this water back,” Bernat said.

Finding water for the state to purchase and pump underground would be an extraordinarily expensive task. Instead, the AWBA buys “long term storage credits,” which is water that someone has put into the ground, but did not pump back out in the same calendar year. Those credits can be sold, but the market for it is limited to specific areas of Arizona. According to the Water Bank’s website, through 2023, it had accrued 4,380,000 acre-feet of long-term storage credits: 3,770,000 acre-feet for Arizona uses and 613,846 acre-feet on behalf of the State of Nevada.

For producers, the AWBA can provide some water through its Groundwater Savings Facility program, but it has never been a panacea. Beyond just storage credits, the state of Arizona also collects a pumping tax on groundwater in AMAs. The AWBA receives a portion of the pumping tax collected by the State, but from 2020 to 2026, the AWBA waived the money collection in the Pinal AMA so it could be used toward agricultural efficiency.

New Visions of Conservation

Arizona and Idaho have two different ways of looking and responding to their water issues. Arizona’s focus on recharging groundwater makes sense for the state because groundwater is the most efficient storage system, and pumping groundwater is how the state has managed to grow at such a remarkable speed. Idaho’s use of a rental market for water allows the state’s irrigation heavy agriculture to rapidly shift water from one right to another without the headache of sales.

But there are other, different ways to “bank” water. The Ogallala Land and Water Conservancy in eastern New Mexico is a partnership between federal dollars and local landowners in one of the most water-scarce areas in the state. OLWC is focused on an area near Cannon Air Force Base and Clovis, New Mexico, where farmers and ranchers have been pumping groundwater to grow crops and water cattle for a long time. A 2022 study showed that the Ogallala Aquifer had lost 20% of its remaining groundwater since it was last measured in 2017. That rapid fall led Dr. Ladona Clayton, executive director of the Conservancy, to create the OLWC and work on a new kind of water banking: groundwater conservation easements.

Like Arizona, the goal of a groundwater conservation easement is to keep water in the ground. Like Idaho, farmers are being paid for their water. The greater goal? Use less water, period.

Clayton said the first phase of the process OLWC has created is working with the USAF and local farmers to get to a three-year agreement that will pay landowners the appraised value of their groundwater, which can be anywhere from tens of thousands of dollars to hundreds of thousands.

“They stay whole, they just retire irrigation wells during the entire term of the agreement,” Clayton said. The next phase is where things shift into a different way of banking water.

The entirely voluntary groundwater conservation easement OLWC has piloted requires 80% of groundwater in the easement area to be saved. The remaining 20% is the landowner’s to do with what they wish, as long as they don’t access more than that metered 20% mark.

“They can or they cannot sell, it’s up to them entirely,” Clayton said. “The only major restriction is no irrigation farming. There can be hunting on the land, they can lease the land, transition to dryland crops, or pursue regenerative agriculture. We want them to stack as many benefits as possible, in order to remain in agricultural production and secure in their financial status.”

Ten landowners have taken OLWC up on this project so far, but Clayton believes the message is a resonant one.

“The greatest selling point for our model and what makes us unique is that landowners step up in partnership voluntarily because the model values their work and compensates them accordingly,” she said. “Landowners will say they can’t believe they haven’t lost ground.”