Saving Water with Fire

Forest health collaboratives are using fire to steward healthy headwaters across public and private land. That hard work flows downstream to all of us.

Jagged, snow-capped peaks tower above a thick canopy of green on either side of the road. In my periphery, ponderosa pines interspersed with Gambel oak come into focus; trees disappear as I enter a tight canyon formed by glacial rivers that are now small streams. I know this route well.

I drive past the turnoff for the Oso Diversion Dam, a Bureau of Reclamation project completed in the 1970s. Banded Peak Ranch sits above it—a 50,000-acre private property encompassing the headwaters of the Navajo River. Other large, private parcels are nestled deep in Colorado’s spruce-fir forests.

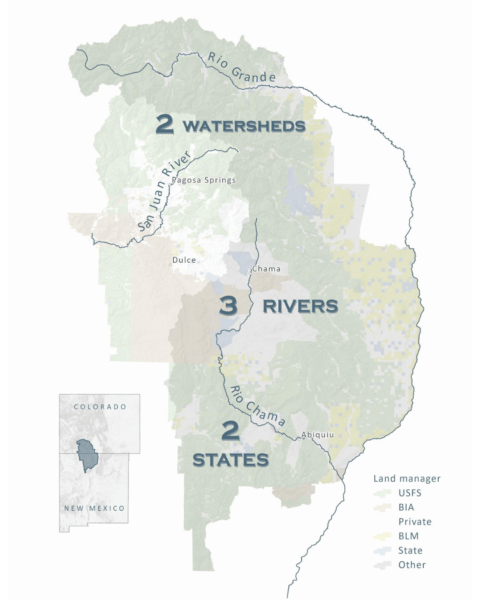

By nature’s design, the Rio Blanco, Navajo and Little Navajo basins feed into the San Juan River, a major tributary of the Colorado River flowing into Lake Powell hundreds of miles downstream—but water molecules originating in the Southern San Juan Mountains rarely find their way to the Gulf of California. Runoff from these basins is rerouted through a tunnel underneath the Continental Divide, emptying into the Rio Chama watershed. The Chama transports this supplemental water to the Rio Grande, which flows over 1,500 miles in a southerly direction toward the Gulf of Mexico. This trans-basin diversion, known as the San Juan-Chama Project, is a critical lifeline for millions downstream in New Mexico. As drought deepens in the Southwest, cities and farms are becoming more dependent on this supply when the Rio Grande can’t provide. This overallocated river system, similar to the Colorado, is struggling to balance increasing demands with a hotter, drier future.

Which is why, when I asked Banded Peak Ranch manager Tim Haarmann what his most pressing concern is, he told me, “I manage with the worry of a catastrophic wildfire, like everyone else in the area.” Haarmann has been stewarding Banded Peak for more than a decade now, and all of that time the region has been in drought. “I feel a major responsibility to downstream users,” he said.

The Rio Grande, above, and its tributary the Rio Chama, below, provide the drinking water for Albuquerque, along with irrigation water, wildlife habitat, recreation opportunities and stunning beauty.

Many others in the region are equally concerned. If a wildfire spread out of control through the overstocked, beetle-killed forests surrounding Banded Peak Ranch, the consequences could ripple far and wide. Drinking water for the New Mexico cities of Santa Fe and Albuquerque would likely be jeopardized, along with agricultural, industrial, environmental and cultural needs throughout multiple watersheds.

“If we think about the watershed strictly from a supply source, the clock is ticking,” says Casey Ish, conservation program manager of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District (MRGCD). The MRGCD serves approximately 11,000 irrigators, six Pueblos and 100,000 parcels of land throughout the Middle Rio Grande Valley. “The question is, are we moving fast enough, and can we move fast enough to make fire more of a tool than a hazard?”

That urgency has land managers, including Haarmann and his neighbors, engaging in a landscape-scale collaboration to minimize negative impacts when a fire does happen. It is a model other regions are embracing across the West.

State and federal agencies recognize the need for the use of prescribed and managed fire to lower wildfire intensity and restore the ecological benefits of fire in fire-adapted forests. Managed fire is a response strategy to naturally ignited wildfires that allows them to burn in useful and low-risk areas. However, complex policies around permitting, liability and ownership boundaries, among others, have rendered this management tool almost inaccessible to private landowners.

“What was destroyed here was not only homes, ranches, barns, corrals, animals, the forest, but the culture burned. To bring everyone back with the same vision of the future is probably going to be the most difficult thing.”

– Hilario Romero, Las Vegas Land Grant board historian

In 2020, a cluster of large and deadly U.S. wildfires following a century of fire suppression led the Biden administration and its public land managers to dramatically ramp up prescribed burns and forest thinning in the West.

These efforts made a complex situation even more complicated when, in 2022, a prescribed burn ignited by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) exploded into the biggest blaze in New Mexico’s history: the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fire. More than $4 billion was spent either fighting the blaze or is earmarked for recovery efforts and monetary compensation for damages. But that daunting figure does not come close to reflecting the long-term costs of the lost ecosystem services of these forests, or the generations of stewardship embodied in the charred homesteads in the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

“What was destroyed here was not only homes, ranches, barns, corrals, animals, the forest, but the culture burned,” said Hilario Romero, a member of the Hispano land grant community in the Sangres and Las Vegas Land Grant board historian, in 2023. “To bring everyone back with the same vision of the future is probably going to be the most difficult thing.” Romero’s great-great-grandfather was one of the original recipients of the Las Vegas Land Grant in the 1830s.

For landowners in the region, it is critical that the right lessons are learned from the Hermit’s Peak disaster to inform that collective vision of the future. “Fire is a critical tool, but there really has been no forest management in over 100 years,” Navajo Peak Ranch owner Tucker Knight explained. “We have an exorbitant amount of timber and understory on this property, with a lot of dead fall…we’ve masticated a few hundred acres up to this point, but the ongoing maintenance is what keeps me up at night.”

Knight’s 5,000-acre property along the Little Navajo hosts one of three diversion points for the San Juan Chama Project. “The first time I ever looked at the ranch, I didn’t have any clue how valuable this watershed is to so many people…we’re trying to do 200 acres a year, over 10 years, but it’s arduous to do it alone.”

That’s where the 2-3-2 Partnership comes in

I drive south out of Colorful Colorado and into New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment, not recognizing the difference. Signs of migrating herds are everywhere along Sargent Pass; animal tracks dot both sides of the Continental Divide. I pass a group of rafts on trailers traveling northbound as the scene gently transitions to sandstone formations and plateaus. A mirage on the horizon hints at a large body of water. Another bend in the road reveals a sweeping view of the Chama Valley, a small agricultural community irrigated by acequias, centuries-old communal ditch systems found in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico.

The highway traces the Rio Chama and eventually joins the Rio Grande, where transmountain and native water supplies merge. A ribbon of green defines the river’s edge, more starkly as the bosquepulses through the heart of New Mexico’s population and into the Chihuahuan Desert.

The 2 Watersheds—3 Rivers—2 States Cohesive Strategy Partnership (2-3-2 Partnership for short) launched in early 2016. It was born out of public interest to address watershed health in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico through cross-boundary forest management, collaboration and planning. More than 5.1 million acres make up the 2-3-2 footprint—approximately the size of Delaware and Connecticut combined. Over half of the lands within this region are managed by the USFS, with private lands accounting for 21% of the area.

The partnership is a team of teams, made up of place-based collaboratives whose geography encompasses or is reliant upon watersheds in the 2-3-2 geography. The dispersed leadership structure is consensus-based and seeks to be neither prescriptive nor burdensome. Partners share resources to address watershed and forest management by leveraging dollars and mitigation efforts across boundaries. The 2-3-2 elevates important initiatives already underway, while increasing the pace and scale of restoration throughout the landscape.

How can we overcome the risk of catastrophic fire in a landscape that encompasses two watersheds, three rivers and two states? It requires challenging the notion of social, political and geographic boundaries.

“Partners are contributing tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of dollars here and there. When you look at the scale of the landscape that needs to be managed, we could not have done that work and gotten the same results [without pooling those funds],” Ish, the Middle Rio Grande conservation manager, told me. 2-3-2 partners “use that money to apply for larger federal dollars,” he said.

Since 2-3-2’s inception, the partnership has secured $30 million in funding and over $5 million in shared resources—with millions more in proposals awaiting decisions. Since October 2022, partners have jointly treated over 6,400 acres through prescribed fire, completed 15,500 acres of fuel treatments and implemented nearly 16,000 acres of watershed improvement.

The collective of Tribal, private, state and federal agencies, nonprofits and research institutions gathers three times a year. The fabric of 2-3-2 meetings is different every time, thanks to its open door policy and rotating locations throughout the partnership geography. While there is an executive committee providing strategic direction, Dana Guinn, 2-3-2 coordinator and partnership manager at the Forest Stewards Guild, encourages attendees to build relationships and challenge their assumptions.

“I work to create the space for people to come together and get to know one another, so that when we have these opportunities to do projects together, we have comfort with the other people that are working on these tough problems,” Guinn told me. “We’re able to take more risks and take on challenges in more creative ways…as the coordinator of the partnership, I believe that is more paramount than any planning, implementation or monitoring that we do. Much of the work happens in between meetings.”

Brandy Richardson (right), public affairs officer for the U.S. Forest Service’s Rio Chama Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Partnership (CFLRP), and Dana Guinn, 2-3-2 Partnership coordinator and partnerships manager at the Forest Stewards Guild, tour a forest treatment site in the San Juan National Forest. Photo by Christi Bode.

Lived experiences around land management decisions have created some deep wounds throughout land-based communities. Polarizing headlines and post office rumors are loaded with fuel. “I think we tend to demonize agency people…when you get to know them as people, you really start to understand what they’re trying to do and the framework that they’re working within and limited to,” Haarmann said. “There’s real strength in that. And hopefully likewise, they can come to me as a private land manager and understand what I’m trying to do as well. Instead of just seeing my eight ‘no trespass’ signs, we’re working together and all have a common goal in mind.”

Private landowners play a crucial role in ensuring the restoration and maintenance of healthy and resilient forests, but they face many barriers to the successful implementation of good, common-sense management on the ground. In parallel, public land managers do as well.

“We are most certainly not the only subject matter experts—and often our role is to show up, listen and understand our community partners better,” said Brandy Richardson, public affairs officer for the Forest Service’s Rio Chama Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Project (CFLRP). “We’re taking that back to our forests and applying that knowledge and feedback to manage the national forest lands within the landscape.”

The Chama Peak Land Alliance (CPLA) is a local landowner-led conservation group in the region. “A lot of these private lands we are representing are a very important part of the geography in terms of ecological values, wildlife habitat, aquatic species and water supply,” said Caleb Stotts, executive director of CPLA. Caleb and the landowners he works with recognize that solutions are unlikely to come from a single entity or a one-off project. For family forest owners, a lack of technical expertise and the high cost of land treatments stand in the way. According to American Forest Foundation data from 2021, mechanically reducing fuels costs, on average, costs between $1,000 and $2,500 per acre.

“Within this [2-3-2] framework, there’s a real diversity of people that you wouldn’t normally be talking with,” said Stotts. “And then you can build momentum, and hopefully, funding.” Collaborative efforts translate into the connectivity of treated acres across private, public and Tribal lands.

Left: The dense understory of unhealthy ponderosa pines provides ample fuel for wildfires and can lead to dangerously hot crown fires that spread quickly. Right: A treated forest has a more open canopy, more diversity in the understory and will allow a wildfire to burn along the ground without killing mature trees. Photos by Christi Bode.

The Rio Chama CFLRP is the largest project of the 2-3-2 Partnership and encompasses portions of four national forests in two states. “We lean on place-based organizations to help engage the community and share messaging. All of this takes time. These groups can show support for prescribed burning that helps the Forest Service ease back into a delicate issue—its incremental steps in the right direction.”

In addition to garnering public support, the 2-3-2 has fostered new programs that fulfill important needs throughout rural communities, where resources are limited. This includes providing wood sources for heating and cooking, supporting workforce development through reforestation programming and enhancing the ability of Tribal partners to engage youth.

I drive back from Santa Fe to the high country, pulling off Highway 84 and onto a dirt road. There’s a pickup with the Forest Service emblem on the door, parked in a rough pullout. Guinn and Richardson are here to show me around a forest-thinning project in the San Juan National Forest.

I ask them, what’s the secret sauce to a successful partnership?

“I don’t do it by myself. The network of people that I work with and alongside is the most valuable capital that I have for moving cross-boundary goals forward,” Guinn says. She insists that measuring success is not as linear as the number of acres treated. It might also be counted in how many people you can call when you need help.

“I don’t do it by myself. The network of people that I work with and alongside is the most valuable capital that I have for moving cross-boundary goals forward. We’re able to take more risks and take on challenges in more creative ways.”

– Dana Guinn, 2-3-2 coordinator

That social safety net is vital when a landscape-scale disturbance, like the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fire, does strike. Catastrophic events like that change the physical and social complexion of communities, sometimes permanently. Unified human fronts have the ability to dig deeper, to be there for one another when the environment is coming undone.

After talking about partnership metrics for a few minutes as we stride through the forest, Guinn circles back around to the recipe for success. There isn’t anything novel about the ingredients, she says. “I think when you value other people above accolades or checkboxes or the amount of money that you leveraged or this statistic or that statistic, it’s really amazing what you can accomplish. That’s the secret sauce.”

A native cutthroat trout rests in an eddy in the Upper San Juan River. Photo by Christi Bode.