Can flood irrigating do what spring floods used to out West?

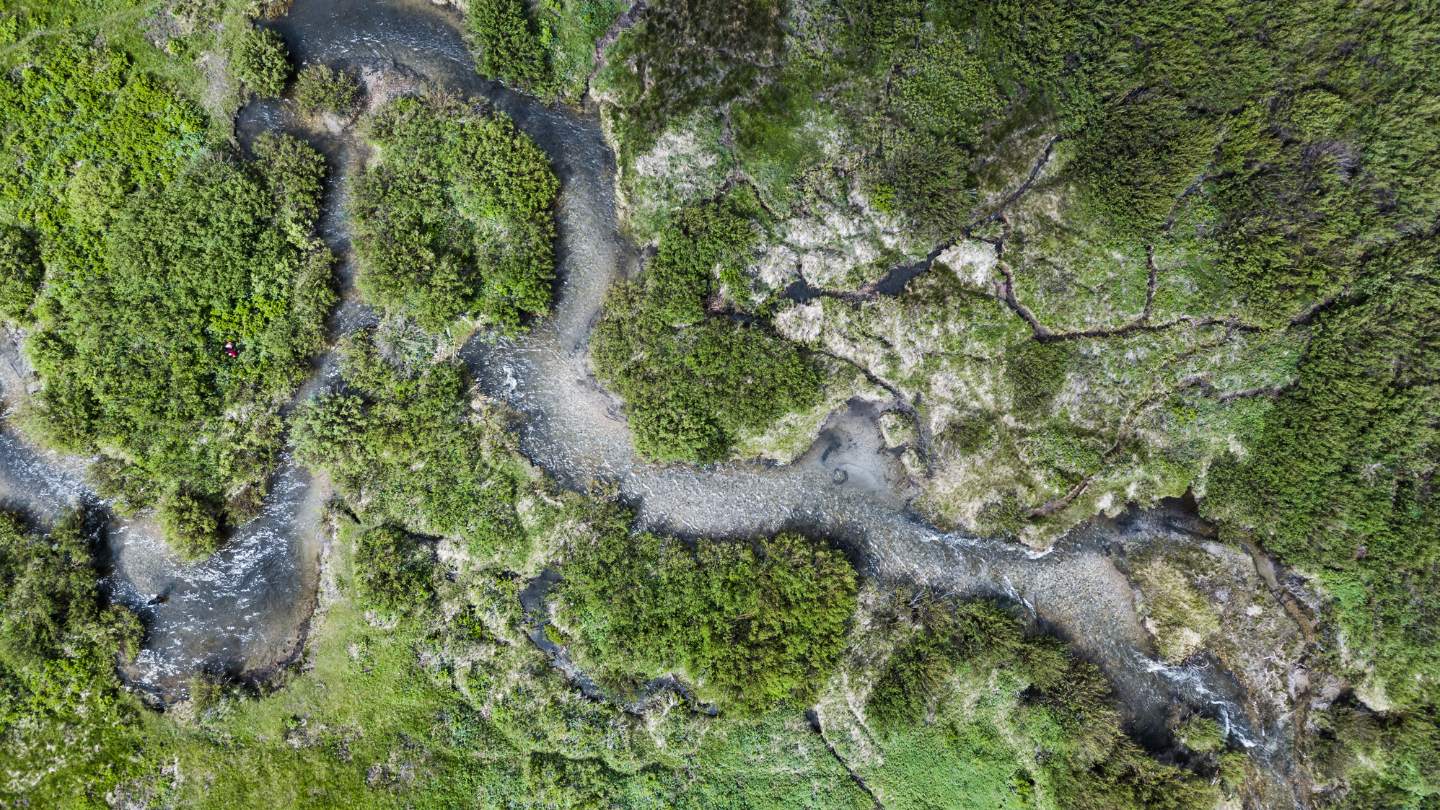

Each spring, Adrian Hunolt draws water from the Bear River to flood irrigate the fields on his family’s ranch in Evanston, Wyoming. Like many other flood irrigators, Hunolt’s ranch lies in a historical riparian ecosystem, where seasonal flooding recharges the groundwater, provides late-season return flows and improves water quality by mimicking natural processes.

“Flood irrigation makes the most sense for us,” said Hunolt. “By saturating the system, we can grow feed for our cattle while sustaining valuable wetland habitat for birds, elk and other wildlife. We’re also seeing flows return later in the year, which means our neighbors downstream are also happy.”

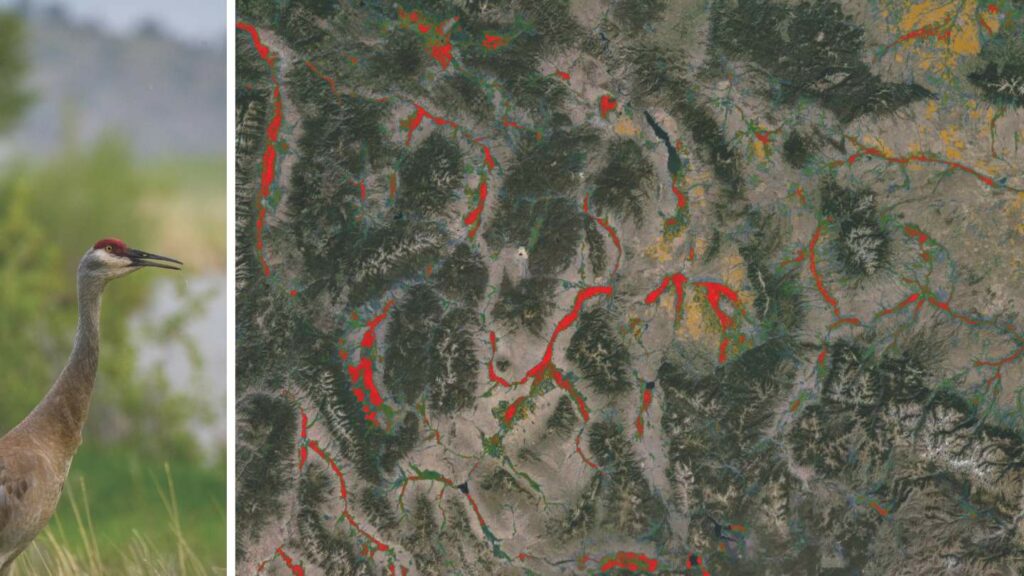

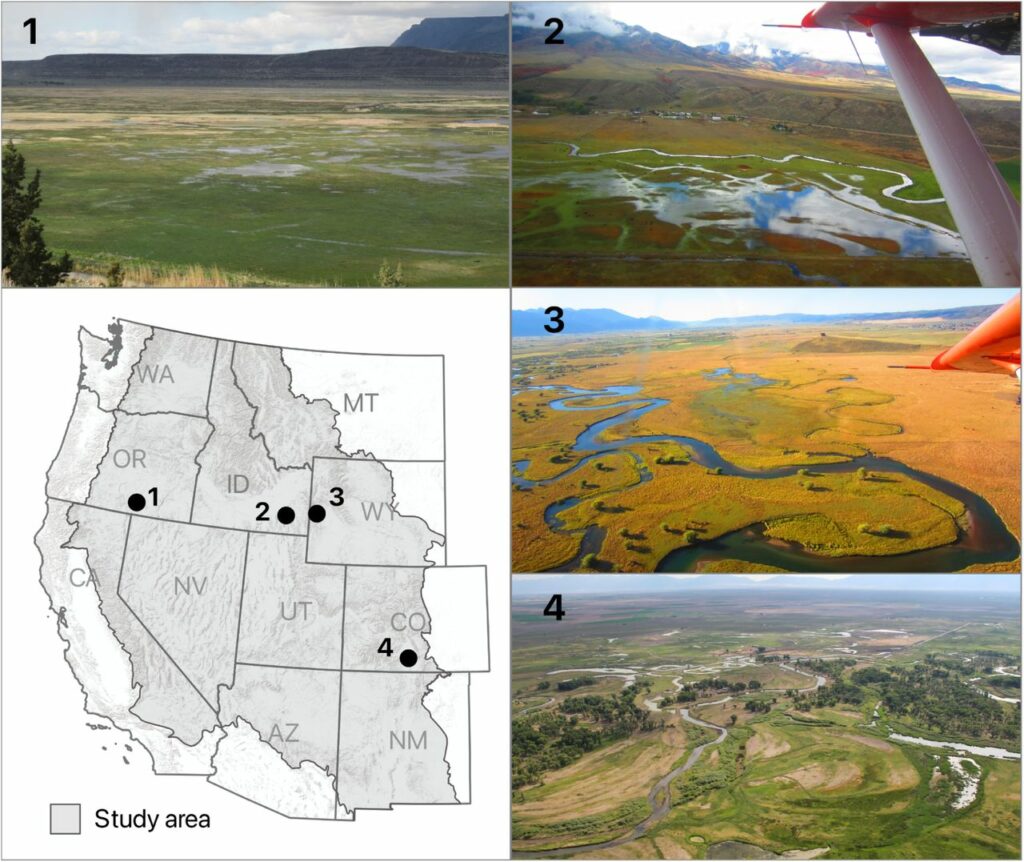

Hunolt is not an outlier. The Intermountain West Joint Venture compiled a comprehensive spatial catalog of grass-hay production in the Intermountain West, integrating it with modeled surface water distributions using satellite data. The study’s findings indicate that flood irrigation of grass-hay coincided with the natural hydrological rhythm (i.e., late spring snowmelt-driven high flows), with approximately 93% of inundated grasslands concentrated in historical riparian ecosystems. Despite constituting just 2.5% of irrigated lands, grass-hay operations played a crucial role, supporting the majority (58%) of temporary wetlands in the Intermountain West—a habitat that is essential, rare and dwindling for wildlife in the region. A related study found that, for example, flood-irrigated agriculture supported nearly 60% of the wetland resources used by sandhill cranes in western North America.

For millennia, the grassy meadows alongside the West’s mountain streams have flooded each spring as snowmelt swells the waterways. The migrations of hundreds of species of birds, large and small, are synced to this seasonal pulse and rely on these temporary wetlands to fuel their flights.

Ranching in much of the Intermountain West has similarly come to rely on these flood dynamics for grass-hay production, which provides crucial winter livestock feed. As water crisis conversations continue, voices promoting water efficiency will likely grow louder. But these new studies are showing that by directing these seasonal pulses of water through flood irrigation, ranchers are mirroring critical natural processes that sustain the West’s wildlife and beauty.

Read the studies

“Beneficial ‘inefficiencies’ of western ranching: Flood-irrigated hay production sustains wetland systems by mimicking historic hydrologic processes.” J. Patrick Donnelly, et al. In Review onland.link/flood-hay

“Flood-irrigated agriculture mediates climate-induced wetland scarcity for summering sandhill cranes in western North America.” J. Patrick Donnelly, et al. Ecology and Evolution onland.link/cranes