When discussing groundwater in agriculture, the mind’s eye tends to conjure a classic picture of a windmill pumping irrigation water from a well to nourish thirsty crops. However, new attention is being paid to the interconnections between groundwater, surface water, and the future of water in the West.

Groundwater, surface water, and their connections

In the intricate dance of nature, surface water and groundwater intertwine, forming vital connections that sustain life across landscapes. Streams, the lifeblood of many ecosystems, engage with groundwater in various ways, either gaining water from it, losing water to it, or fluctuating between the two depending on location along the stream bed. This exchange ensures that streams continue to flow even during dry spells, drawing on the groundwater’s steady contribution between rainfall or snow melt.

Beyond streams, other surface-water bodies like lakes and wetlands play their part in this hydrological symphony. They, too, receive groundwater inflow, recharge groundwater, or engage in both processes, shaping the intricate web of water movement across, and beneath, landscapes. Yet, this interconnectedness isn’t merely physical; it also extends to water quality. Nutrients and chemicals dissolved in surface water can seep into the connected groundwater system, altering its composition and influencing ecosystems downstream.

Recharging the aquifer

Like a handful of other states, Montana is exploring innovative strategies using groundwater and aquifer recharge to address water management challenges. In many parts of the state, natural water storage occurs in winter snowpack and expansive alluvial aquifers, which are crucial for sustaining irrigation and streamflow during late summer and fall when water demand peaks. However, the shift from flood to sprinkler irrigation practices gradually reduces aquifer storage over time by minimizing irrigation seepage. Moreover, climate change impacts further exacerbate the situation by diminishing winter snowpack.

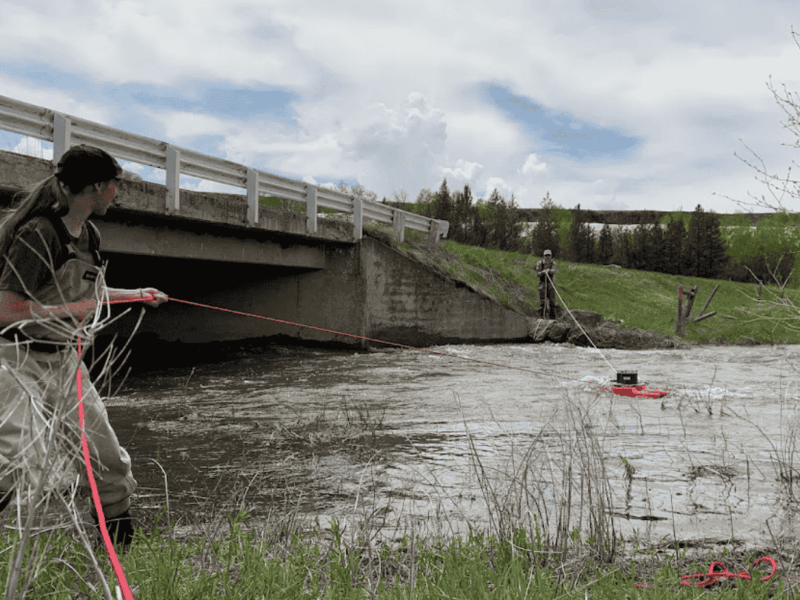

The Montana Bureau of Mines & Geology’s Ground Water Investigation Program (GWIP) is accumulating data to better tell the story of the state’s groundwater and its relationship to surface water and the land. By studying not only the impact of irrigation methods but also land use change and the effects of development, the GWIP creates detailed groundwater maps, comprehensive datasets, and scientific reports to help regulators, senior water-rights holders, new water-rights applicants, and other stakeholders make better-informed water management decisions.

The traditional narrative surrounding groundwater in agriculture is evolving as attention shifts towards understanding the intricate interconnections between groundwater, surface water, and the future of water management in the West.

Through this work, landowners and water users in Montana’s Big Hole Valley have expressed an interest in using alternative approaches to actively recharge the aquifer to enhance water storage capacity and bolster resilience against droughts. This concept, known as “managed aquifer recharge” (MAR), encompasses various techniques aimed at replenishing aquifers using surface or underground recharge methods. One approach to MAR, as discussed in Montana, would allow groundwater wells to inject water taken during periods of high water flows directly into the aquifer below, which, once stored, could be pumped out later in the season when needed. This approach could help replenish aquifers, support wetlands, sustain domestic groundwater wells, and maintain groundwater contributions to streamflow.

In addition to addressing storage challenges, aquifer recharge could offer secondary benefits, such as mitigating the impact of warming temperatures on streams. During late summer and early fall, when water temperatures rise to precarious levels for aquatic life, the return flow from recharged aquifers could provide a cooling effect, safeguarding vulnerable species.

Elevating the underground

The traditional narrative surrounding groundwater in agriculture is evolving as attention shifts towards understanding the intricate interconnections between groundwater, surface water, and the future of water management in the West. By actively recharging aquifers, water storage capacity can potentially be enhanced, and additional benefits such as supporting wetlands, sustaining domestic groundwater wells, and mitigating the impacts of climate change on streams can also be realized. As we navigate towards a more sustainable water future, these efforts underscore the importance of holistic approaches that recognize the interconnectedness of our water resources and ecosystems.