Recently, a young man asked me how he could get into the ranching business. I told him there were two ways: inherit a million dollars or win the lottery, then ranch ‘til it runs out. Even those of us who have been in the ranching business for several decades are scrambling to make a profit.

I find that a good reality check is to compare the number of calves it takes to buy a new pickup now and when I started 65 years ago. The weaning weight of steer calves has risen from about 325 pounds to over 650 pounds and the price has risen from 18 cents/lb. to $1.40/lb. And yet it takes almost twice as many calves today to buy a pickup as it did in 1956. So, how does a rancher stay in business when we buy our supplies and equipment at retail and sell what we produce at wholesale?

It can be done, of course, but mostly by those who inherited a large piece of land or large estate and have no kids in college. Realistically, those of us who are hanging on usually have alternate sources of income. This can be recreation (fee hunting, trail rides, guest ranch, etc.), other natural resources (timber, firewood, fence posts, gravel pit, etc.), or an outside job (drive the school bus). As a matter of fact, many of us are able to continue ranching because our land values continue to rise and we can borrow against the increased value of our ranch. The real cop-out, however, is to sell the north 40 to a developer. I call that a cop-out, but can we really blame a rancher who, after 50 or 60 years of scrabbling to raise a family and never really getting ahead, decides to sell a small parcel of land that might run four or five cows, for 10 or even 20 times what he paid for it?

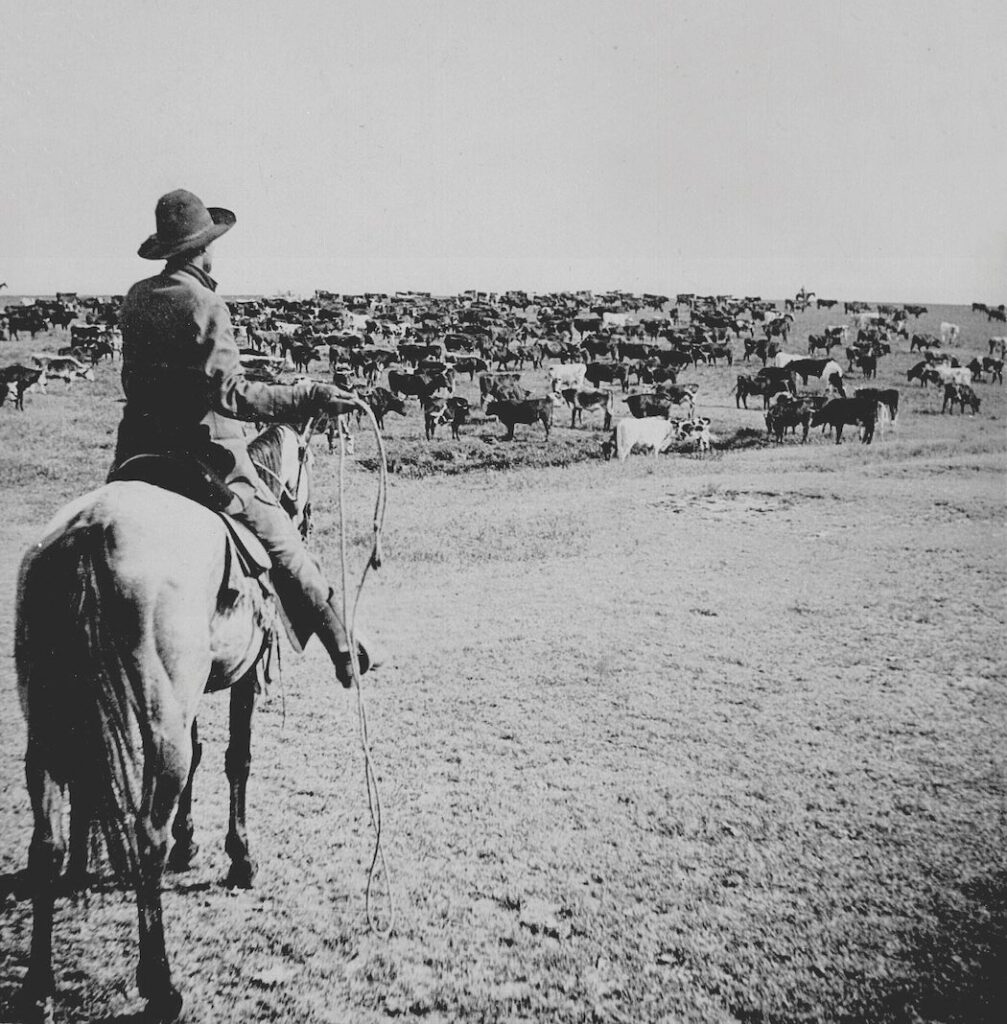

Ranching in the ‘Old West’

Where did this all start? What was it like in the “Old West”? What will ranching be like in the “New West”? To put this in perspective, let’s go back to the days just after the Civil War. Cattle in Texas and other Southern states had multiplied during the war to the point that a few good cowboys could put together a herd of free-roaming cattle and head up the trail to Dodge City. If they survived the stampedes, floods, Jay Hawkers and Indians, they could make a profit. There was enough demand for beef back East to provide a good market for three- to five-year-old steers that could be had for a song. The female stock came here to New Mexico, Arizona, and states north all the way to Canada and by the turn of the century, the cattle boom in the West was at its peak. As an example, in the Smokey Bear District of the Lincoln National Forest (just east of Alamogordo, New Mexico), there were 82,000 head of livestock in 1902. Today there are less than 5,000.

There is no feeling like catching the old wild cow that escaped the last three roundups or feeling the strength and willingness of a good horse under you as day breaks miles from the nearest house or road.

When I was a kid cowboyin’ on ranches near Albany, Texas, I was fortunate enough to ride and work cattle with older cowboys who had actually “gone up the trail” with those herds. They were my heroes: gentlemen, wiry and tough, they knew which way a cow was going to turn before she took a step. I was able to absorb their philosophy and understand those things that counted most to them: which horses in your string would buck; which horse you could depend on to stay in a mile-eating lope when you had to ride the outside circle; which horse you could use to cut cattle out of the herd (and you made sure no one else rode him!); when and where was the next rodeo and how many cases of screwworms did we pick up today? There was always talk of rain, fences and Saturday night. Good-natured competition on ranches and between ranches was always present. All of those things were part of cowboy camaraderie and they were much more in vogue than range condition, biodiversity and endangered species. In those days, living close to animals and the land was wonderful therapy. There is no feeling like catching the old wild cow that escaped the last three roundups or feeling the strength and willingness of a good horse under you as day breaks miles from the nearest house or road.

So trailing cattle north and establishing ranches, then finally settling down to raise a family on those ranches occurred as the frontier came to an end. Although the American way of life became steadily more urban and industrialized, ranching in the West remained relatively unchanged. Hollywood nurtured the cowboy or rancher image as a little wild when he got to town, but he was honest, a respecter of women and his word was his bond. For the most part, I this found to be true. Those cowboys and ranchers that I worked with became role models for young men like me. As far as land stewardship was concerned, the emphasis was on livestock, water, fences and round-ups rather than ecosystems.

Environmentalism comes to the range

It was not until 1970 when the first Earth Day was observed that I, at least, became aware of the environmental movement. As Congress passed more and more environmental legislation and the public developed an environmental conscience, ranchers, miners and loggers became targets. Ranchers were told, usually by young, overzealous, inadequately informed people, that they were incapable of properly managing their ranches and permits. This, of course, was true in some cases. Regardless, the majority of those individuals were engaged in an ambitious, century-old, cumulative race to mollify the wild enough to scratch a living out of it. Neither they nor their offspring were programmed to take advice from anyone who had not walked the walk.

In the Smokey Bear District of the Lincoln National Forest (just east of Alamogordo, New Mexico), there were 82,000 head of livestock in 1902. Today there are less than 5,000.

Herein lies the root of misunderstanding and subsequent conflict in the Western states. No credit was given to those who had settled the West in spite of the immeasurable hardships they faced: drought, blizzards, lawlessness, rustlers and family tragedies. They were condemned for their lack of concern for the health of the land. No allowance was given for their lack of knowledge of the brittle environment they found as they moved west from areas of higher precipitation, where you could run an animal unit to 8-10 acres instead of 40-60 acres. If those pioneer cattlemen came west in a good year, they thought they had found Paradise, not knowing that a three-year drought might be just around the corner. Their priorities were family security, homes, schools, water, barns, building corrals and fences, livestock and land ownership — not biodiversity.

Shaking off the frontier hangover

We are finally emerging from that “nature conquering” scenario, but some of us old-timers still suffer from a “frontier hangover.” We want to follow in Dad or Granddad’s footsteps because “he did alright!” … and we respect his knowledge and experience. The reality is, we now must look at our natural environment as a complex partner that has beneficial qualities, if we use the right approach. As a land steward, with over half a century of experience, I see this, in an ecological sense, as the “New West.” It seems to me that using this approach addresses many of the issues that need to be moved up on the priority list. Setting goals that result in a properly functioning watershed should be at the top of the priority list, and then things begin to fall into place. The components of a healthy watershed — vegetation, riparian areas, fire, drought, wildlife habitat, grazing and recreational use — must be managed holistically and that management must be monitored so that in the end we have economic and ecological sustainability.

What could be more gratifying than seeing an expanse of headed-out blue grama, dirt tanks holding water, a healthy woodland and cattle lying down chewing their cud by midmorning?!

All of the water on Earth that is available to plants, animals and people must first pass through a watershed. When we start to look at a watershed as an entity of its own, or a “whole,” and realize that it has an existence other than the sum of its parts, then we are ready to tackle the massive watershed rehabilitation challenge ahead of us. The public and Congress have finally realized that water shortages and disastrous wildfire can be remedied by addressing that challenge. The Forest Service Fire Plan and the BLM Fire Management Plan plus some “319” grants and other monies that are becoming available provide some funds, but those funds will have to be matched by landowners and communities. Federally assisted, locally led projects are being developed in most of the Western states and will certainly be a major player in the ecological New West.

New West or old, ranching still has that major handicap — almost everything we buy, we buy at retail, and we sell our product wholesale. Environmentally sensitive ranching has lowered that handicap somewhat for me — in that I give to the natural processes rather than push against them.

To survive in the future, we must not only consider the needs of our ecosystems, we must manage our business using a sound, science-based approach. If we are unable to adjust and consider at least some of the holistic approaches to management, we will probably end up selling to a developer, and in doing that, we run the risk of compromising our Western heritage.

Neighboring

I was recently asked why it is important to keep ranchers on the land. My answer was “values.” Do you value open space, wildlife habitat or quiet? What about a place away from mercury lights where you can really get a look at the stars? How about what I call rural values? Let me give you a couple of examples of what I mean by rural values.

Many times I have asked a rancher I have just met if he or she knows the Smiths or Joneses that live in their area. The answer might come back, “Yes, we neighbor.” Some folks don’t realize neighbor can be a verb. What does it mean to neighbor? In the spring when its branding time, when calves are shipped in the fall, when a fence is down or a water gap is out, when you are sick or hurt, or when you leave town for your son’s or daughter’s wedding or graduation, a neighbor lends a hand. Rural values also influence and mold children raised on a farm or ranch in a beneficial way. Watching the neighboring process imbues in them a selfless “help first” attitude. Having the responsibility of caring for animals every day regardless of weather, school activities, holidays or weekends develops dependability and self-assurance. Starting cattle work before daylight, fixing fence, cleaning corrals and the dozens of other jobs around a farm or ranch develops a work ethic that lasts a lifetime. People who love, understand and know how to care for the land are hard to find in today’s society. Growing up on the land provides the foundation for those qualities.

Cautious optimism: the cowboy way

What are our major concerns for the future on both public and private land? On public land we are dealing with a legacy of custodial management by the Forest Service and the BLM that has resulted in overgrown forests as well as grasslands invaded by piñon, juniper, mesquite and sagebrush. In the Cuba area of New Mexico, 55% of our grasslands have disappeared since 1933. Future concerns are overwhelming recreation — uncontrolled ORV traffic and lawsuits that have resulted in nonaction, even when the bureaucracy is willing to move. Over 50% of all the new vehicles purchased in America these days are SUVs or side-by-sides. We can’t continue to kick the grazing dog on public land. We must prepare for the recreation impact that will surely come.

On private land, subdivision and second homes threaten not only our remaining open space but our Western way of life as well. As an example, fire is required for a healthy forest and control of invading water-hungry plants, but second homes (exurban development) scattered over the landscape make proactive use of fire (aka prescribed burning) very dangerous or impossible. Scientists and ecologists, once at odds with ranchers, have concluded that larger, intact, working cattle ranches are crucial puzzle pieces holding together an increasingly fragmented Western landscape. Subdivisions not only disrupt watershed function, but the dogs, cats, ATVs, dirt bikes and invasive plants that come with them are a very real problem to wildlife, and livestock. What would you rather have on your watershed — trees and grass or roofs and pavement?

Yet, I see some bright spots in the future of ranching

- Cattle numbers are down. If the supply is down, demand and prices should rise.

- El Niño seems to be nibbling away at the drought.

- Assistance is available for those who want it — from the federal government through the Farm Bill and increasingly from states and private foundations and nonprofits. Many ranchers don’t want that sort of assistance, but hard times make strange bedfellows.

- Hopefully, the Healthy Forest Initiative will speed forest and rangeland restoration through increased thinning, prescribed burning and expedited environmental review for the many necessary projects.

- The public may have to pay to enjoy uncluttered landscapes (an example might be found in Irish subsidies for agriculture). Good stewardship should be rewarded in some way that supports economic sustainability and regenerative agriculture.

Now, after a memorable and wonderful summer, the holistic land steward rancher is being rewarded for his or her attention to land health. Innovative and sustainable methods of land stewardship, the improvement in grazing management and bovine genetics are finally making ranching a profitable endeavor. Not only do we love what we do but now we can say we did “make a difference.” What could be more gratifying than seeing an expanse of headed-out blue gramma, dirt tanks holding water, a healthy woodland and cattle lying down chewing their cud by midmorning?!

Our task for the future is to preserve our Western way of life by passing to those who follow us a work ethic that we have developed and our knowledge and love for the horses and cattle we husband. The “Cowboy Way” still means what it did 100 years ago.

Sid Goodloe has owned and operated Carrizo Valley Ranch, north of Capitan, New Mexico, for more than 55 years. He is the founder and president of the Southern Rockies Agricultural Land Trust.