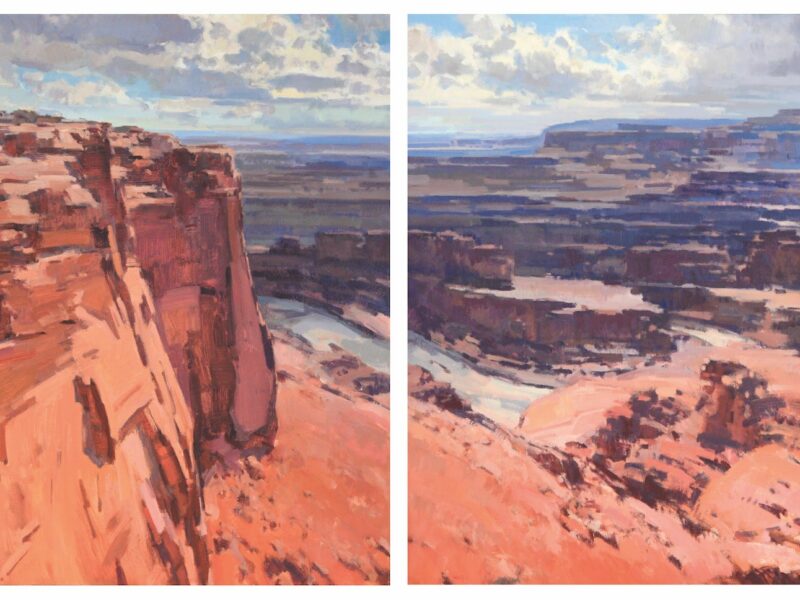

Clyde Aspevig’s paintings capture the imposing grandeur of the West. He hopes the arts can help save it before its too late.

Aspevig is a master of landscape painting. Today, he lives in Bozeman, Montana, but Aspevig grew up on his family’s historic homestead near the Canadian border outside of Rudyard, Montana, population 258. Mother-and-son team Carolyn Quan and Kelly Bennett recently spoke with Aspevig about his life, his art and the legacy of the West that he communicates through his paintings.

Carolyn Quan & Kelly Bennett: Let’s start with your early years, growing up on a working landscape. What was it like?

Clyde Aspevig: Both sides of my family were homesteaders. Primarily dryland wheat, but we also had cattle, pigs, horses, chickens … everything. My grandfather’s farm, where I spent most of my childhood, was pretty much self-sufficient so I saw all the different aspects of agriculture, ranching, and how one survives out in the middle of nowhere. I still remember as a little kid on my grandfather’s farm that we didn’t get electricity until about 1956. Growing up in this isolated area gave me a different perspective when I went to college in Billings and then did some traveling, but it has always resonated with me.

CQ/KB: When did you discover art?

CA: My interest in art was always fostered by my parents since I was a little kid. Both of my parents were very musical … all my aunts and uncles played and sang. Especially after WWII, I grew up in an environment of great celebrations, music constantly, the community halls, family get togethers. I had an uncle who was a farmer and one summer, my dad was sick and I broke my leg and my uncle got me started painting. He was an amateur painter himself. I wasn’t one of those kids who grew up thinking that being an artist was being sissy — they encouraged me to pursue art. I still have the canceled check from the first painting I ever sold, which was to my father for $10 the year that he was dying. It was of the Sweetgrass Hills. I never looked back and always wanted to be an artist. I had a professor in college, Ben Steele, who was an amazing man and who became a surrogate father for a bit. He helped me pursue art; I started doing watercolors and he would get the other professors to buy them for $20 each.

CQ/KB: Were your first paintings landscapes or did you start with different subjects?

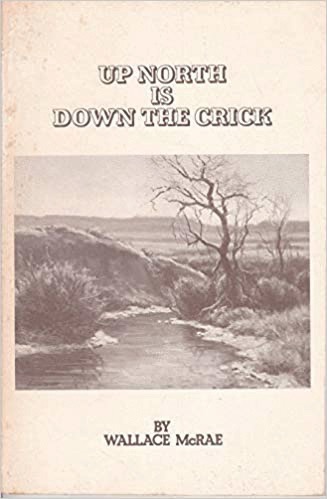

CA: I was drawn to landscape because that’s what surrounded me. I remember Sunday drives in the five-county area [of Montana] to look at the wheat growing, just filling my mind with big landscapes. I did old buildings and paddocks of horses and animals and illustrated Wally McRae’s Up North Is Down the Crick with pen and ink of ranching life and wildlife. As I evolved, I did more landscape because landscape is where all of our lives play out. It is the platform of how we live and how we are shaped by the environment around us.

Wally McRae, the Great Cowboy Poet

Up North is Down the Crick was Wallace “Wally” McRae’s first of book of poetry. He went on to become the first cowboy poet to win a National Heritage Award from the National Endowment for the Arts. Now 86, he and his son, Clint, manage the 30,000-acre Rocker 6 Cattle Company Ranch near Rosebud, Montana.

Up North Is Down the Crick, illustrated by Clyde Aspevig.

CQ/KB: How have you seen that “shaping” change?

CA: My work has always resonated with a more pristine landscape, but that’s complicated because pristine may mean the pastoral to some people and to others it may mean the wilderness. I have experienced both in my life. When I’d get off the tractor, what I enjoyed most after all the noise, was this beautiful silence. I could go in the coulees and pastures that hadn’t been broken out by my ancestors and it was a whole different world. You could look for circles of stones, experience wildlife and the cacophony of the sounds of the natural world. Then you go into the barn and we would be calving and you hear the sounds of animals.

Landscape in my art is about trying to engage the viewer, because this communication is a two-way street, and how they perceive it. That’s what I love about pure landscape: and it strikes the imagination and resonates with people from all over the world. If there is one thing I’ve learned everyone has in common, it’s the appreciation of a beautiful landscape.

CQ/KB: How does the communication work between you and a viewer of your art?

CA: This is when you get into the big picture of the arts and the humanities. The first thing when the viewer engages is their response in the form of a narrative. It provokes a story. It’s so powerful an emotion that you can’t help but escape, whether you want to call it romanticism or idealism of a landscape. It provokes an emotional response that is embedded in our psyche as human beings. Landscape is a universal language. The minute I put a person, wildlife, a horse in a painting, it becomes about that specifically so it narrows a viewer’s response, and that’s OK, but is less about the landscape and its possibilities. It sounds hokey, but when I paint, I’m thinking about the vibration of things. I use texture to create an organic feeling of movement and when the light hits the canvas in a certain way, it reflects it differently and creates that idea of sound, of engaging the senses. It’s hard to explain, but I get that from viewers of my work: “I feel like I’m there. …”

CQ/KB: Some of your paintings feature relics of past human activities. What is the nexus of working landscapes and wild landscapes through the lens of your art?

CA: One of the things that is amazing about our human character is that we love to explore. We love to go across the horizon to see what’s on the other side and that’s what a lot of those landscapes are about. Those relics are also part of what Nature does: In the end, things decay, fall down, change. It is the most powerful force that humanity will ever come up against; it takes an enormous effort to keep our manmade things going. If we don’t understand Nature and use it according to what we know about its regeneration, about taking care of it as the source of our resources, then whatever I paint really doesn’t matter. The reason I paint these relics is to remind people that we are not permanent here, that things continue to change and that we should recognize that. We are at a time now that if we don’t reconnect with the environment, have we outdone ourselves and has the technosphere overtaken the biosphere? That’s what these paintings are about: reminding us that Nature is king.

My work has always resonated with a more pristine landscape, but that’s complicated because pristine may mean the pastoral to some people and to others it may mean the wilderness.

Clyde Aspevig

CQ/KB: How should the community of working lands stewards communicate with the rest of the population? Can it happen through the humanities?

CA: For years, I have advocated for regular national holidays from the humanities, when you voluntarily for one day, take all the paintings off your walls, remove all the art from your life, no music, disengage from all things creative. For just one day, think how you would feel — it would be terrible. We have taken the humanities and the arts for granted because they have existed since the beginning of time. Our landscapes may be similar. Among the farmers and ranchers I know, and I know many, there is one thing they all share: the idea of the beauty of a sunset, the beauty of being out there in the landscape. That is common to most people, too, especially when they move to a place like Bozeman or any town with these surroundings. We have to help them see how harsh it is now in the middle of a megadrought. Wheat prices are going up like crazy and yet you can’t grow anything. It’s hard to make a living on the landscape. We have to ask, how are we going to live in this balance in this complicated world? We need to sit down and have a serious conversation about it and we can use the humanities as a platform for common ground to bridge the gap between rural communities and urban people. If we all agree that we enjoy the beauty of a landscape, that is a starting point. If we instill in ourselves the love of a landscape and the beauty of it, how it changes throughout the day, it produces a kind of empathy that translates to a broader sense of who we are and how we get along.

A working landscape to me is a very broad thing — everything from wilderness to ranches. We should understand people’s connection and livelihood that is tied to the ground and we should understand that recreation is another part of our working landscape. You need the flexibility to adapt as a landowner. One of the most difficult things I’ve witnessed in my time growing up in Montana is the death of the small towns. Big ag had a lot to do with that. A working landscape today needs alternatives that allow you to stay on the land and we may need to experiment with different models.

That’s what these paintings are about: Reminding us that Nature is king.

Clyde Aspevig

CQ/KB: What is the most important thing that you communicate in your art to people who have an urban perspective of landscapes?

CA: I hope that I can convey to them to be careful how they use them. I’ve seen some of the most beautiful places around the world get ruined by too many people loving them to death. I’d hope that people could learn to appreciate how fragile these places actually are. I can foresee the growth of Bozeman creating a huge challenge to how we maintain our lands. People are unaware of their impact until it’s too late. We have to let people know how special these places are and hope they listen to the fact that we can’t just squeeze every last drop out of them without destroying what attracted us to them in the first place.

CQ/KB: What do you hope a rancher who sees your art takes away?

CA: I hope they realize how special their land is and how it can fit into the big picture of the world. We have to be great stewards and that’s not easy. It tests one’s courage to deal with change. You have one of the most unique spots in the world and it is a huge responsibility to take care of it properly.

CQ/KB: We are in polarized times where collaboration is challenging. How do we come together to preserve the legacy of the West?

CA: Why is it that the dry earth, when the rain hits it, smells so good? It’s a form of beauty, of aesthetic, that appeals to something in all of us. We need to instill an appreciation for it in our kids (there’s the same kind of beauty to be experienced for city kids), because it is a powerful common ground. It gets lost so quickly in this heated environment right now. It’s a difficult task to get people on opposite sides to the middle. If you look at history, when you start in the middle, you gain more of what you’re trying to get than starting at the extremes and inching to the middle. When you go to Shakespeare in the park around Montana, you see ranchers and hippies and all kinds of people with smiles on their faces, united in listening. That gives me hope that the humanities can help us find common ground and cultivate more empathy, which is the most important thing.