The Colorado River Basin Cannot Survive Without Major Changes

Last week, the Bureau of Reclamation released the draft Environmental Impact Statement evaluating post-2026 operation alternatives for managing the Colorado River reservoirs after the expiration of the current operating guidelines at the end of the 2026. Negotiations between the states in the Colorado River Basin have been stalled, and every minute without radical action is a minute that will have enormous downstream impacts on health and human safety, agriculture, ecosystems, and the West as it currently exists.

The problems on the Colorado River are huge, and it is clear the current crisis is too big to be solved by the existing systems – ecological, community and economic damage are inevitable if new adaptations are not developed and adopted quickly. We at Western Landowners Alliance believe that the people of the American West can find another way.

With a slow start to winter in the Basin, the Colorado River is staring down a runaway freight train with runoff predictions among the lowest ever seen in the region. There’s too much to do, too little time, and too many social barriers to head it off at the pass. The Colorado River Water Users Association (CRWUA) annual meeting in December was of little help to water users, as posturing from states and threats from the Department of Interior demanding states find consensus were the message of the hour.

The problems on the Colorado River are huge, and it is clear the current crisis is too big to be solved by the existing systems – ecological, community and economic damage are inevitable if new adaptations are not developed and adopted quickly. We at Western Landowners Alliance believe that the people of the American West can find another way.

But giving up the fight is not the answer. Maybe we can’t stop the train, but we can slow it down.

Per the work of the Colorado River Research Group, another year like last year will lead to less than 4-million-acre feet of readily available storage in the major reservoirs to make it through the winter of 2026-2027. If that’s the case, we have to act now to prevent a full collapse that could compromise infrastructure and the ability to deliver water to downstream users. Waiting until the expiration of the current operating guidelines at the end of 2026 will be a death sentence for the Basin’s ability to function.

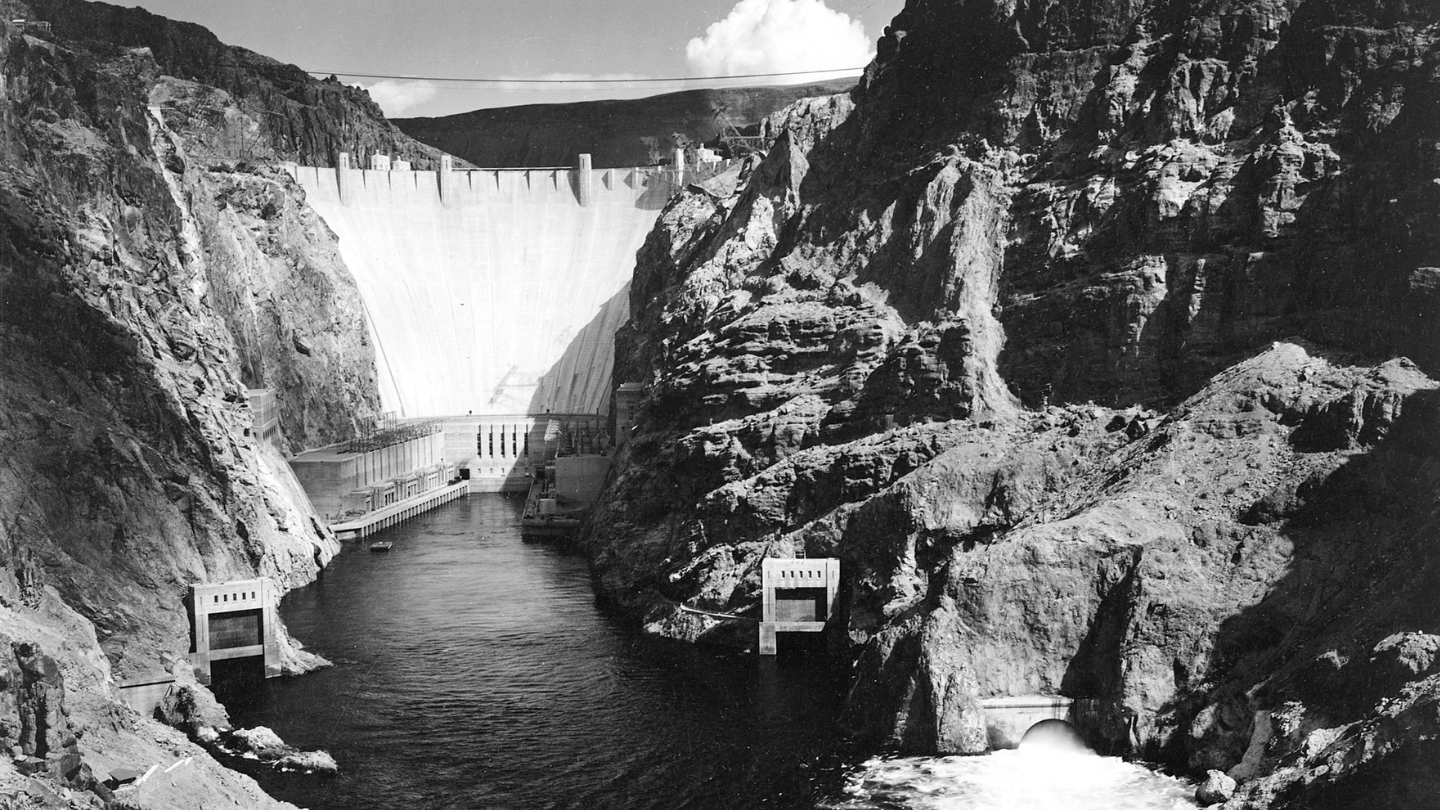

As drought continues to dry the West, the inaccessible water contained in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead will be necessary to prop up the failing system. The dams and water distribution systems were designed with much higher water levels in mind, so accessing that storage will require expensive construction projects. And construction takes time, something the basin is woefully short of at the moment as negotiators continue to bicker away the water savings accounts that took decades to build. But we can’t stop there. Our relationship with agriculture and water management in the West must shift to accommodate decreased water supplies. How we grow crops, what we grow, how we manage land and agricultural markets must also shift, which will require the commitment of producers, governments, and people everywhere. We must act quickly and boldly to prevent catastrophe. The Colorado River Basin is quickly moving beyond the realm of voluntary conservation measures and agricultural production and into triage to protect basic human health, including drinking water and sanitation in the West’s largest cities.

The Colorado River Basin is quickly moving beyond the realm of voluntary conservation measures and agricultural production and into triage to protect basic human health, including drinking water and sanitation in the West’s largest cities.

Once the water is gone, it’s gone. Catastrophic damage to wildlife, ecosystems, and rural communities becomes inevitable, and the harm only starts there. To prevent impacts, including another Dust Bowl event, invasive species, and wildfires, these changes must be undertaken proactively. WLA knows that projects like wet meadow restoration, forest management, and riparian flood plain restoration increase water storage, slow runoff, and improve drought resilience. Upgrading century-old irrigation systems saves water, reduces labor, supports crop viability, and improves stream flows. By prioritizing investments in soil health, crop transitions, and risk-reducing tools, private lands that support much of the West’s wildlife and ecosystem services will stay viable under hotter, drier conditions.

All of these practices protect rural livelihoods and maintain open spaces, but the cost of these practices is high, and too great to be borne by private landowners alone. The entire southwest, including cities and rural agricultural communities, depend on the Colorado River. Healthy watersheds and functional farms and ranches reduce wildfire risks, improve water quality, support biodiversity, and stabilize regional economies. If the headwaters and working lands fail, downstream communities will feel the pain.

As a basin, we must work collaboratively now, or the cost will be exponentially higher in the future. Major infrastructure must be modified now to allow access to all stored water. Congress and federal agencies must expand and sustain watershed, irrigation, and drought-resilience funding. Programs must be streamlined and include long-term commitments. Investing in landowners is investing in the resilience of the entire Colorado River Basin.

Landowners are ready to be part of the solution—but they cannot do it alone.