Irrigation efficiency is something all producers should strive for, right? Or wrong?

Agriculture uses a lot of water. And with water getting scarcer in many parts of the West, it seems logical that agricultural producers should try to seek efficiency in their use of water. One apparently low-hanging fruit is the shift from flood irrigation to sprinklers, a potentially valuable change for producers in states looking to conserve water. But the science is leery of saying that irrigation efficiency actually conserves water, and a new study in Rio Blanco County, Colorado suggests chasing efficiency could be inefficient.

Studying flood irrigation along the White River

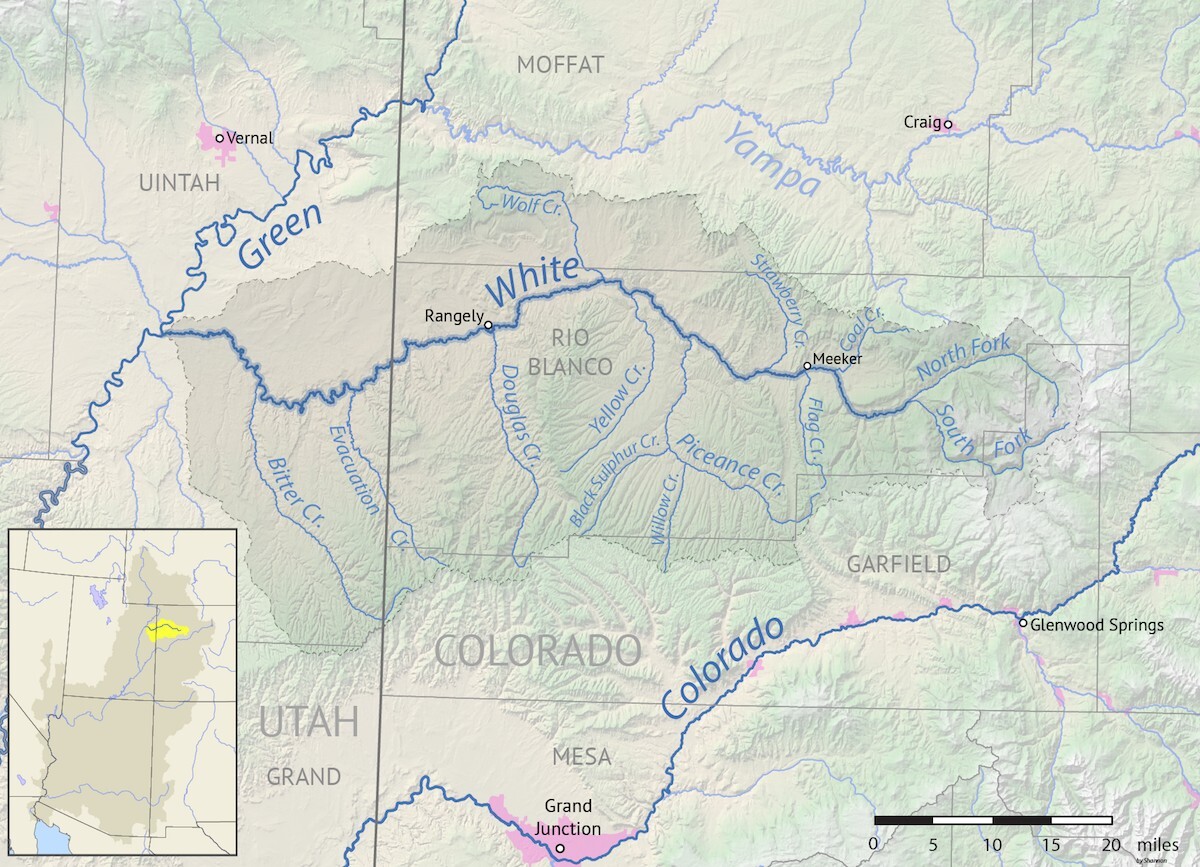

A key-shaped 3,223 square mile parcel of western Colorado just north of Grand Junction, Rio Blanco County is home to huge herds of elk and mule deer, ranching families, world-class trout fishing and the White River. The 195-mile long river is a tributary of the Green River, which in turn flows into the Colorado River. Rio Blanco County also is home to a significant amount of flood-irrigated fields, a truly ancient form of watering plants and animals.

Digging trenches in a field of crops and letting water flow through them is one of the oldest forms of irrigation. Called either “flood” or “furrow” irrigation, this style of watering crops is remarkably popular across the world because it is both cheap and low-tech. In 2000, 29.4 million acres of land was irrigated by flood irrigation. While there has been a push for more efficient spray irrigation in the dry American West, it turns out flood irrigation serves an interesting conservation purpose in this part of Colorado.

The second year of an ambitious three-year study of the White River’s underground life came to a close at the end of June. Designed by Colorado State University Professor Ryan Bailey and supported by the White River and Douglas Creek Conservation Districts, White River Integrated Water Initiative, Colorado Water Conservation Board and Colorado River District, the project created a hydrological model of the White River’s life above and below ground. Replicating the study could eventually help other regions in the state create their own models and will inform and direct future scenarios and management decisions for the White.

“There are a lot of stories in Rio Blanco that the river ran dry in the winter, and while we have not been able to find anyone to verify that, that is a widely held belief in the area that without irrigated agriculture, it would be partly or nearly dry in the river,” said Liz Chandler, watershed coordinator for the White River Integrated Water Initiative, a community-based organization dedicated to promoting the health of the watershed.

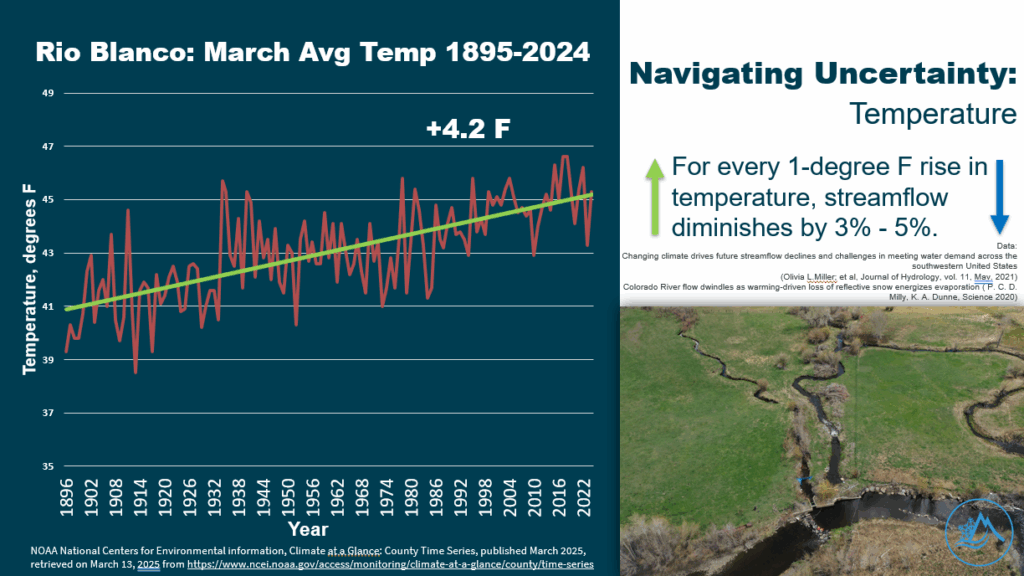

This study comes at a critical time for the White River. Since 2000, the average river flow has declined by 20 percent. Part of this is due to climate change and rising temperatures in Rio Blanco County. Since 1895, the average temperature in March has risen by 4.2 degrees Fahrenheit, which correlates with studies showing that for every one-degree Fahrenheit rise in temperature, streamflow diminishes by 3-5%.

“The question is: what is the efficient use of water?” said Chandler.

Sprinkler irrigation and lining canals with impermeable plastic coverings are known to make water use more efficient. That efficiency in turn leads to more water use, a double-edged sword where precise application of water leads to more efficient evapotranspiration for crops and includes sprinklers’ ability to pull water from lower water levels in irrigation canals. These lead to more water being used by crops and less water being returned to the groundwater table below the earth. According to the study’s modeling, flood irrigation water can be used five or six times in Rio Blanco County before it leaves entirely, something that would not occur if sprinklers and their more efficient evapotranspiration capacity were the irrigation style of choice.

Where the Action Is

In a 35 mile stretch of river below and above the town of Meeker, there are 30 ditches that divert water from the White River. The study determined 80% of the water diverted into those ditches makes its way back into the White River over a period of several months. Furrow irrigation, it turns out, plays a significant role in keeping the White River flowing throughout the year.

“Lot of people think when you’re flood irrigating you’re wasting a whole bunch of water and it evaporates, essentially it goes underground and returns to the river underground in a few days or months later,” said Forrest Nelson, owner and proprietor of the White River Ranch in Rio Blanco County. Nelson and his family run cattle and sheep on their property and use the White River to irrigate their hay fields.

Two ditches run on the plateau called the Mesa above Nelson’s property and two ditches provide water for agriculture and as it turns out, wildlife, riparian areas and the White River itself. The Highland Ditch and Miller Creek Ditch run for miles on the Mesa, Nelson said, and those ditches are where a significant portion of the return flows to the White River appear again after their trip through the ground.

“On our place it pops out at the bottom of that basin, comes out along the edge, four or five parts where it runs year-round, and looks like a freshwater spring,” Nelson said. “One of those big ditches was off a few years ago, and the springs ran way less water.”

Nelson’s cattle get water from those return flow springs which stay warm enough during the winter to not freeze over. Nelson’s sheep also use return flow springs during the winter, but neither sheep nor cattle would be drinking that water if flood irrigation was stopped, according to Professor Bailey.

“If they either stopped irrigating or didn’t divert as much, that water would go downstream in the spring and summer, and wouldn’t be sustaining groundwater flows,” Bailey said. “Groundwater moves more slowly underground, takes a few months to make its way through the river, irrigating in the spring and summer comes back in fall and winter.”

Indirect Benefits

Another reason flood irrigation works so well on this section of the White River is the “ecosystem services” provided by the removed and returned irrigation water. According to the National Wildlife Federation, an ecosystem service is “any positive benefit that wildlife or ecosystems provide to people. The benefits can be direct or indirect—small or large.”

The study’s data and modeling shows without flood irrigation, there would be a large drop in the water table and wetlands would no longer be replenished by the return flows. Those wetlands are shelters for an incredible wealth of animals, plants and livestock, according to local landowner and Colorado Parks and Wildlife game warden Bailey Franklin.

A third-generation cattle rancher, for the past 24 years Franklin has been working for CPW, a position that has given him a different perspective on the importance of ecosystem services which in turn provide economic services to rural communities as well.

“As a landowner I think it’s good to know that our flood irrigation practices are not efficient by any means but give a lot of indirect benefits to the community,” Franklin said.

The perceived lack of “efficiency” provides a significant boon to wildlife species, particularly for two of the biggest herds of mule deer and elk in Colorado. Those herds have a large impact on the area, Franklin notes, because “our community relies on big game hunting economically.”

“Moving our cattle, managing our habitat, our people are thinking about our habitat and want our wildlife to flourish, without those herds a lot of these ranches would go away,” Franklin said.

Liz Chandler concurred.

“[Agricultural irrigation] is important because it supports wildlife which supports outfitters for hunting season, if you took away the wetlands it would make a big difference to the area,” Chandler said.

The value of this kind of study could be easily translated to other communities who are interested in the value of irrigation for their local watershed, according to Melissa Wills, the Colorado River District’s community funding partnership program manager.

“This model brings so much more of a tool for other communities to follow suit with,” Wills said.

Forrest Nelson believes this kind of study is of direct benefit to landowners like him.

“This study proves the fact we can continue flood irrigating and be a benefit to the community rather than a hindrance … It proves to me that we’re doing a good job and we should be able to continue it and that’s the purpose of the study; to make others realize that it is a benefit to the river system,” he said.