I don’t remember the name of the rider who called us that early morning in mid-July, 1982. We had a lot of turnover at the grazing association in the early 80’s. I remember that his wife put cheddar cheese on the apple pie last time we went up and I considered that sacrilege. My teenage brain was still fuzzy at 5 AM and I was weighing the options of an unplanned trip to the upper ranch versus moving irrigation pipe and spending the rest of the day in the hayfield.

I began to realize that choice might not be part of the equation. Dad started calling his partners, poured the rest of the coffee into a thermos and pointed at the door: “boots, riding not irrigating, and a jacket. We’re going up river.”

Two hours later we were saddled up and riding out across a pasture to somewhere near coyote knoll. The skies were bright blue and the air was crisp, maybe 40 degrees. A typical summer morning in the Big Hole. To call us, the rider had to drive 10 miles to a neighbor’s place, because a lightning strike from an early afternoon thunderstorm the day before had taken out the telephone. The line ran along a ridge, and we typically lost it at least once a summer. There were scorch marks on the wall of the house in the kitchen surrounding the old bakelite wall phone. To his credit, after discovering the demise of his means of communication he waited for the storm to pass and rode out to check the stock. That’s when he came upon 14 cows and calves killed by a lightning strike. Standing close together in an irrigated pasture, they had been killed by conductivity and their own gregarious nature.

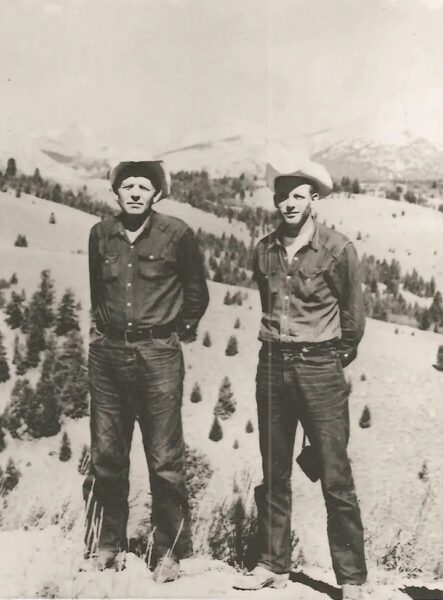

Death by lightning in these high mountain pastures is not unknown, but these numbers were impressive, so I guess that is why we rode out. That and curiosity, confirmation, mourning — who knows. Our party included me, my father, our rider, and Don, a grazing association partner and a World War 2 Army Air Corp veteran made of sinew and seasoned with whiskey and tobacco.

Everyone in our group was a more experienced rider than me, so when their horses started acting up they were much better at handling it than I was. It was too early for there to be much smell of decay, but ruminants keep generating gaseous byproducts of digestion for a while after death so we reasoned that might be the problem. The horses kept dancing for the next quarter mile as we approached coyote knoll, and as we crested the rise and looked down the other side we saw the cattle laid out in a 50-foot circle about 100 yards away. One of them didn’t look right as we came over the hill. The color was wrong. It was a little too small. Then it sat up and looked at us. The moment it sat up, we knew. Don uttered, “Well I’ll be God damned,” my dad with his classic “sonofa…” That was my first grizzly.

The bear was too full to move much so we sat on our spooked horses and watched him for a few minutes until our patience with our mounts wore thin, and we rode to the next pasture to check the rest of the herd.

Lived experience on the land

These were men who had spent their entire lives on the land managing livestock. They made a good share of their living based on observation: animal health, range conditions, plant communities, predators. They had seen a lot of bears over the years and those were predominately black bears, no matter the color phase. This was new. They had seen grizzlies in Yellowstone in the 60’s but more importantly they knew how to recognize a fundamentally different creature. Ranchers are landscape-specific expert naturalists.

So now, here we are 40 years later sitting in the cab of the pickup about a mile from coyote knoll. My wife, Jami Murdoch, is telling me about why this set of images from a game camera is special as she slips an SD card into her laptop. Since we first met at Montana State University 30-some years ago, I have learned to follow Jami’s instincts for finding good subjects. As the first few frames start to pop up I can see we have more of the usual: cows and elk, but about the fifth video stands out. It’s just dawn and a large bear wanders by the camera trap. It pauses and pivots almost daintily with one back paw raised to sniff the rub pole, then turns and slowly meanders away. There is no doubt in my mind about the species of this bear; characteristic shoulder hump, small ears, dished face and silver-tipped hair over its shoulders and back.

We have known grizzlies are on this land for at least 40 years. We have seldom had trouble. Usually we find tracks. In 2003 we had some heifers scratched up but that bear shifted to elk calves. A 2-year old grizzly cub was rummaging at a ranch garbage dump in 2015 so we cleaned up the dump and started using a county transfer site 12 miles away. We are suspicious that that same bear is the one that gets into our remote water trough weekly and steals the ball for the float valve. Our neighbors have seen grizzlies and worked around them for decades. Our current rider even has names for specific bears.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) only confirmed their first grizzly in the Big Hole in 2016. Prior to that date they did not exist, officially.

That “officially” is what rankles Jami. In 2009 we started documenting the wildlife on our main ranch to provide an inventory of sorts. Agriculture is often blamed when it comes to calling for regulations to protect threatened and endangered animals and we wanted to show what we provided for wildlife in terms of habitat, migratory food stops, and respite. We have been wildly successful on our own property, but over years working with conservation groups and agencies we were exposed to eyerolls of doubt, and conversations thick with condescension when we, and others who live on the landscape, talk about species that aren’t officially there. We’ve seen a lot of species that “shouldn’t be there.” Fortunately, with more data on our side, our local knowledge is gradually becoming more accepted by the “experts.”

Agency biologists often spend 30 or less days in the field each year. They’ve earned their expert status through six or so years of higher education, but that’s not the only, or even the best way to acquire expertise. Yet, too often, people, like my father, his grazing association partners, our range rider, and Jami, who are on the ground daily, observing and occasionally interacting with these animals, have their experiences discounted.

Documenting recovery

That’s why the photos that Jami is showing me on the laptop in the truck are so important. We have decided to not wait for government or university studies that could take a decade or longer to prove what we already have seen with our own eyes. Jami has partnered with MTFWP to camera trap and set up DNA traps to sample bears with the expressed goal of identifying whether these bears are most closely related to the Northern Continental Divide population or the Yellowstone population.

The Big Hole Valley sits between these two designated grizzly recovery areas, so even if the great bear is delisted that won’t apply outside of those initial zones. We are hopeful that landowner-led documentation can lead to a greater level of understanding and thoughtful management. With photos and DNA samples, we may yet prove genetic dispersal between the two groups. This would be momentous, not only for the species long-term genetic diversity, but also to further support a change in listing status.

The Endangered Species Act is a tool that has been used as a legal barricade to ranching and other land management practices in many places, often without thought to the unintended consequences to the broader community. That community includes flora, fauna, and humans. Poorly-considered ESA roll outs in the last 40 years have led to just 5% species recovery, despite enormous financial investment by taxpayers and losses on working lands. Reducing costs, protecting habitat and sustaining vibrant rural communities will take more science partnerships like ours between ranchers and agencies.