Habitat restoration on private land happens more often than many think, and is more critical to biodiversity conservation than most recognize. 80% of threatened and endangered species depend on private land for some or all of their habitat. Ongoing stewardship and conservation by landowners are critical for their success.

Just a few days after Jim White, aquatic biologist for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and his colleague spotted the smoke of what would become the 416 fire, they were riding ATVs through a smokey haze up a remote drainage. They drove as far as they could, then trekked with large packs and electrofishing equipment into the creeks where the cutthroat were. Fire burned around them, and they had only a few short hours to catch as many fish as they could.

By the time they arrived back at their truck with bagged fish—exactly 54 of them—in hand, the journey had really only just begun. The already tenuous existence of the species had just become more so.

Eventually, White and his colleagues would turn to Tim Haarmann, the ranch manager of the 52,000-acre Banded Peak Ranches in southern Colorado for help buoying the species.

But we’ve stepped into this story midstream.

Before the bags of fish and before Banded Peak, before the fire, we weren’t certain this strain of native cutthroat existed at all.

Headwaters threats

Cutthroat trout were widespread before Western settlement, but with the expansion of mining, logging and ranching came the depletion of native fish stocks, and the introduction of non-native fish for both food supplies and recreational angling. Development, logging and grazing altered the cool, clear, and fragile stream habitats that they rely on, and mining contaminated the water. By the late 20th century, the distribution of native cutthroat had shrunk to a tiny fraction—roughly 9 percent—of their historic range.

“So there’s a long backstory as to why cutthroat trout are so rare these days, but essentially, it’s the introduction of non-native trout species and habitat destruction,” White says.

Many fish biologists suspected in some cases, and knew in others, that most basins in the southern San Juan Mountains were, at one time, home to cutthroat trout with genetic markers unique to those specific basins. They’d confirmed this for some strains, but as the science around genetic testing advanced, they began to suspect that there were more unique variations than they thought.

Whether or not those species still existed on the landscape? That was a mystery.

Rediscovery

In 2012, researchers began digging deeper. They were digging, literally, through preserved specimens at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

“The cool thing is it all sort of lines up. If you think of the San Juan River Basin, what separates cutthroat trout from getting here is warm water in the Colorado River. They were isolated with that warmer water after the glaciation periods 10,000 years ago; Colorado River warms up, they can’t really swim through warm water, so they’re stuck in the San Juan River Basin and over time they start to become genetically unique and look a little different. They do all the natural evolution stuff that the fish do,” White said.

Over the years that followed, biologists continued to identify potential strains and gather tissue for genetic testing. Wildfires—specifically the West Fork Fire—threatened two of the suspected populations, highlighting their vulnerability.

And then in 2018, two things happened almost simultaneously. First, scientists became confident enough to announce publicly that the San Juan cutthroat was indeed a unique strain of cutthroat, based on its genetic connection with a preserved trout specimen that had been collected from the San Juan River near Pagosa Springs in 1874. And second, White watched smoke rise from the drainage where they had suspected, and could now confirm, two of six existing populations remained. That stream of smoke quickly became a plume, and before the day was over, Jim and his colleagues were working with fire responders to hatch a rescue plan.

Refuge

After the rescue mission’s success, and with the fish at the hatchery, White needed to find places on the landscape to expand the population so that the species wouldn’t be so vulnerable to future fire—to real extinction. But how do you bring back a population of fish? Where do you put them? White needed a place to breed brood stock, and additional streams to raise fish in, so he could create resilience by expanding the locations of existing populations.

While there were some options on public waters, they proved challenging. Most were already inhabited by non-native competitors, and there was always the concern about “bucket biology” on stretches accessible to the public.

But at Banded Peak, White knew the San Juan cutthroat would have refuge, and a safe place to gain a foothold.

Banded Peak Ranches wasn’t a new partner for White. It had been working with Colorado Parks and Wildlife for nearly 35 years, and the ranch had already expressed an interest in helping with the recovery of the native cutthroat. Another two of the six known populations existed on, and were aboriginal to, Banded Peak. White knew he could count on the ranch, and Haarmann, as a partner.

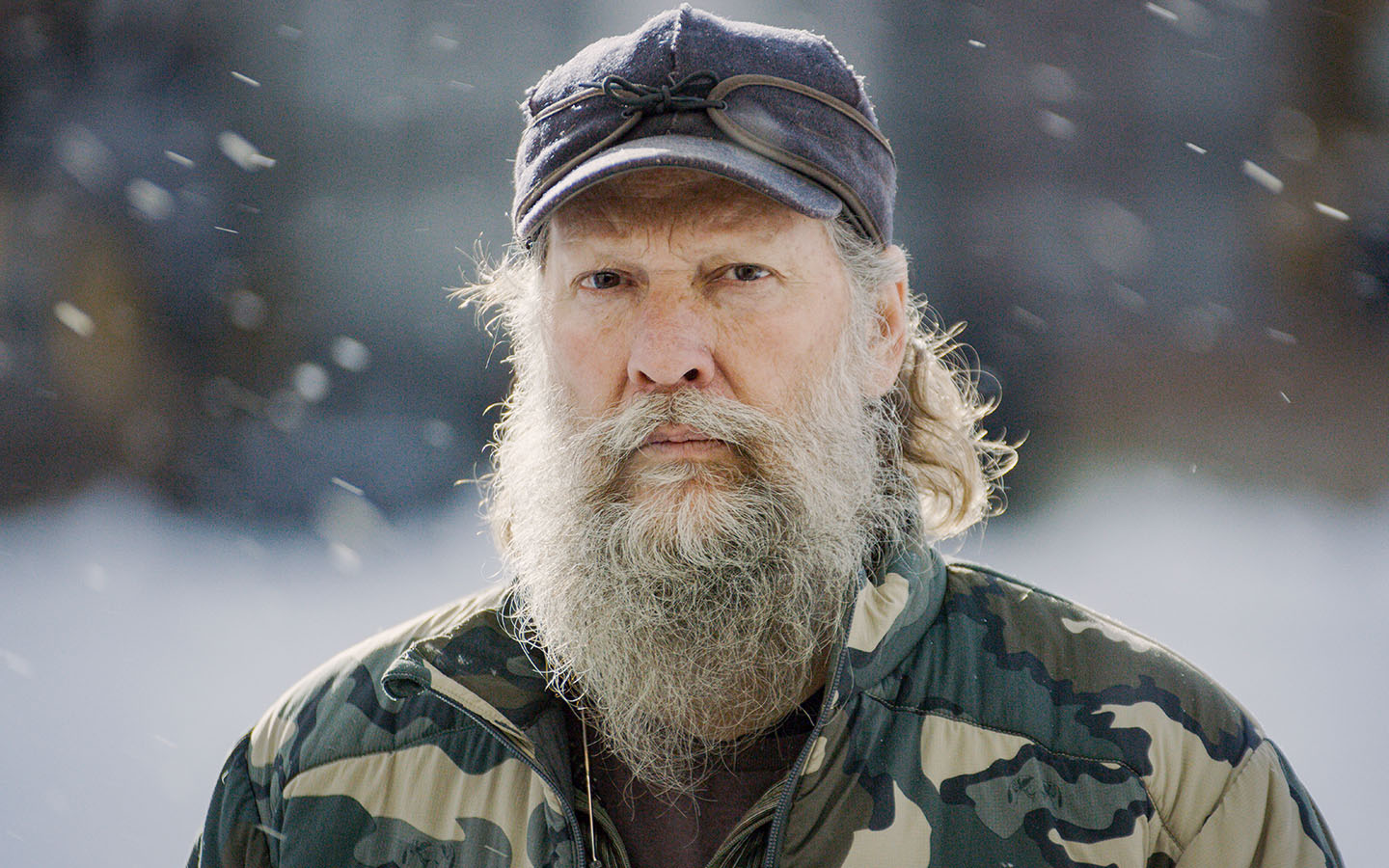

Haarmann is a Ph.D. ecologist. He did his doctoral work at the University of New Mexico, with a focus on ecosystem ecology. After a stint in public land management, and then managing another large ranch, Haarmann was enticed by Banded Peak, the conservation ranch he’s managed for the last seven years.

“As a biologist, I was pretty excited to learn about the recent discoveries with the cutthroat trout, and that the ranch happens to be home to a couple streams with a San Juan strain of the cutthroat,” Haarmann said.

In October of 2020, White drove a population of San Juan cutthroat to Banded Peak Ranch to relocate them in a brood pond that Haarmann had established to help promote the recovery both on and off the ranch.

“The idea is that these fish will grow up and then someday, we’ll come back when they’re adults and be able to take spawn from those fish and propagate new streams with the San Juan cutthroat trout,” White said.

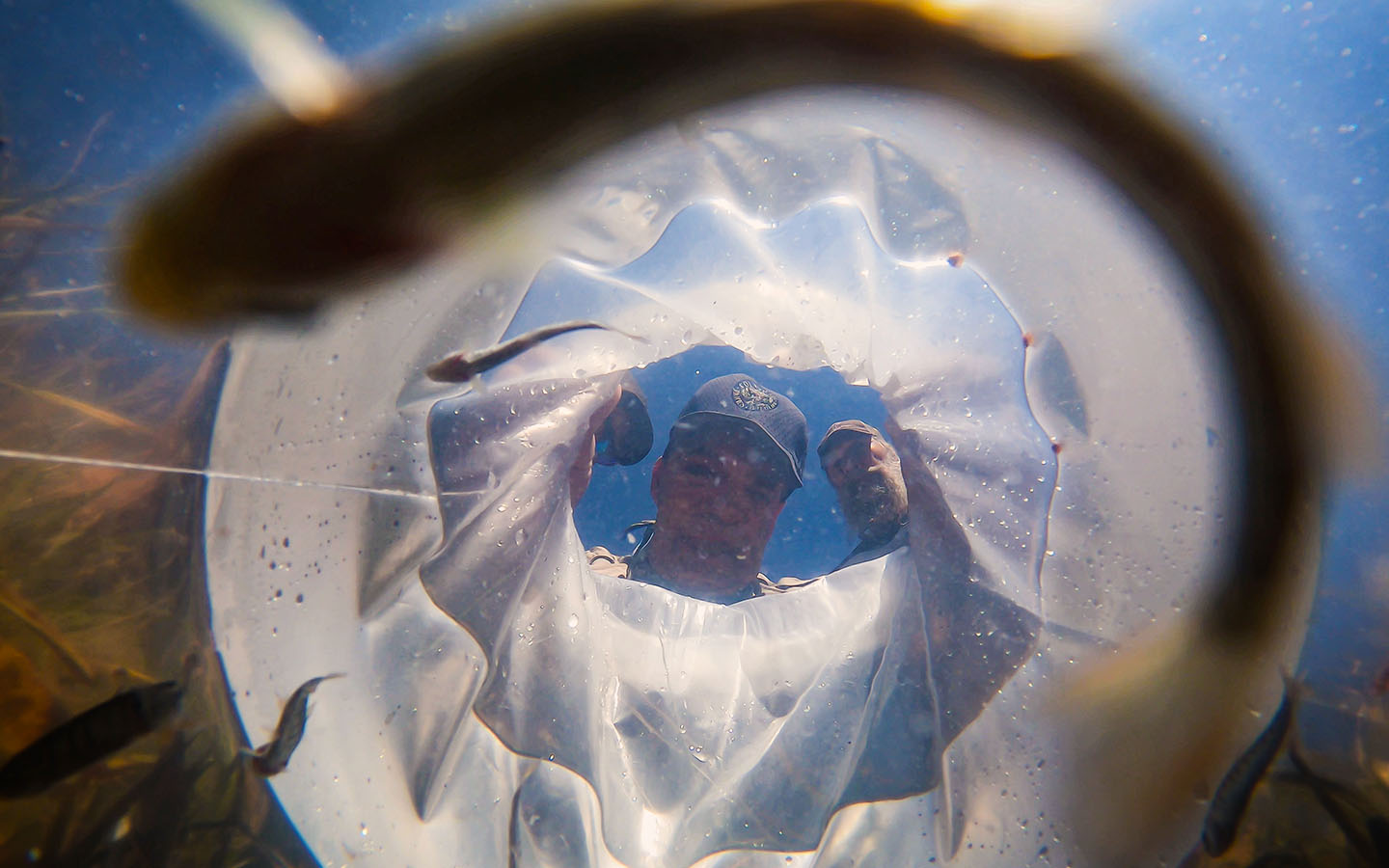

The surface of the small pond mirrored the aspen and cottonwoods that stood starkly in glowing contrast to the sky made hazy by wildfires farther West. Haarmann and White stood together on the shore of the pond, preparing to release the fry—young trout—that swam circles around the bag in White’s hand. He bent down and placed the bag in the shallows to rest, bringing the temperature of the water in the bag into equilibrium with temperature of the pond.

“We absolutely believe it’s critical to invest in biodiversity,” Haarmann said. “We think that anytime you have an opportunity to take a unique organism and preserve it and protect it, it’s worth the resources. Given the amount of biodiversity that we’re losing globally, I think any effort that we can take to preserve species is well worth it.”

Later that day, White hiked up a small creek on the ranch with the fish in a bag in his backpack. He stopped at a relatively mellow stretch of water and poured the fish in to try their lot.

“There’s this emotional side of it where you feel like you’re making a difference. You’re expanding this population of rare cutthroat trout. There’s also a very practical part of this, which is that by increasing these populations, you reduce the threat of them becoming a listed species. Sometimes we see folks that are very against conservation projects not sort of realizing, well, if we expand this fish population, it actually is good for your business as well because we’re not moving towards a tighter regulatory environment,” White says.

For Haarmann, the San Juan cutthroat restoration is an unfinished story, and it’s one without a guaranteed ending. While he’s optimistic about the reintroduction, there are a lot of factors outside his, or anyone’s, control.

“I think everyone was really excited about these different strains of Colorado cutthroat trout, and I think we were all very pleased to realize that there were a couple streams on private land that we were able to work with and help recover this species. I think there’s a place at the table for everyone with these collaborative projects, and this is a really perfect example of all these different agencies working together for the recovery of a species,” he says.

“We absolutely believe it’s critical to invest in biodiversity.”

Tim Haarmann

Swimming upstream

Gwen Kolb works for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program—often simply referred to as the Partners Program—a voluntary program for private landowners looking to do restoration and conservation work on their lands. While she’s held her current role as the state coordinator for New Mexico since 2016, she’s worked with the Partners Program all over the United States since 2001.

For Kolb, species don’t stand much chance without involvement from private landowners.

“These folks know this land. They know it better than we do,” Kolb says. “I can’t restore no Walmart parking lot. If these people start selling their land because of the challenges of regulations, I can’t do my job no more. We’ve got to keep these people on their land. Got to.”

Kolb works closely with Ecological Services, the arm of Fish and Wildlife tasked with, in her words, “maintaining the little bit of stuff we’ve got left.”

While all federal agencies are tasked with enforcing the Endangered Species Act, Kolb’s role is different. Her job is to build trust, and to find solutions that work for landowners, and for the plants and critters that rely on their lands. That isn’t always easy.

“What I find and what I see with landowners is that they’re afraid because if they have an endangered species on their property, they’re concerned people will come in and try to stop them from doing what they’re doing, trying to make a living. That’s a very common fear,” Kolb says, “and I don’t blame them.”

“I can’t restore no Walmart parking lot. If these people start selling their land because of the challenges of regulations, I can’t do my job.”

Gwen Kolb

Agreeing on purpose

Stacy Davies, who has managed the Roaring Springs Ranch in eastern Oregon for over twenty years, has grappled with the implications of providing habitat for endangered species, and he’s worked closely with federal partners, including those from the Partners Program, to bring species back from potential listings.

“Wildlife are really important to us,” Davies said. “And the habitat that supports wildlife is really important to us. We want to be good stewards and allow native populations of both plants and animals to thrive, but we need economic activity on the ranch, and primarily that’s livestock grazing.”

Davies laments—and certainly he isn’t alone—that historically the Endangered Species Act has been a tool for nonlandowners to force landowners into management practices, and that there’s been a lot of money and time spent on litigation, fighting and paperwork.

When the redband trout was petitioned for listing as endangered in 1997, Davies didn’t duck away from the conversation. Instead, he secured a seat at the table through what are broadly referred to as Assurance Agreements [see “Regulatory assurances” for details].

“Some landowners think they can hide species on their property and some make an effort to do it, but in our case, there was no doubt that the species was there [on the ranch], that it had a much larger range at one time, and that it was in peril.”

The ranch became proactive, working alongside resource managers to develop a Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA), which would then roll into Safe Harbor agreements if the species was listed. In 1997 the CCAA was filed for redband trout with the goal of restoring fish to 80% of their historic habitat while maintaining the economic viability of the ranch. The USFWS, Ecological Services, Malheur Wildlife Refuge, Bureau of Land Management, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, and Roaring Springs Ranch all signed the agreement.

“By agreeing upon purpose, both the economic health as well as the environmental health, we all could work together for both, and we had to keep both in mind as we made decisions,” Davies said. “We feel that those agreements allow for wise and efficient use of resources, and we don’t see litigation or heavy-handed regulation as effective ways to manage land.”

For Davies, who has participated in numerous collaborative efforts, the legally binding aspect of the CCAA is part of its appeal. Although perhaps counterintuitive, the agreement actually facilitated more flexibility and on-the-ground adaptation for Davies and the federal land managers he worked with. Further, it brought additional resources to bare on the ranch: through the agreement, he had access to biologists, ecologists, and other specialists who could help him achieve the restoration goals he had for the ranch. “There was benefit to the species, and there was benefit to land management, and for me personally, it was just an opportunity to learn a lot.”

Davies says if the agreement hadn’t been in place, the work still would have been happening, but there wouldn’t have been communication. And, without that, the USFWS could have made a decision about listing the redband trout in a vacuum, and the resulting regulations associated with the ESA would have come down on the ranch. “There’s no doubt that without the CCAA and the efforts put forth within it, that it would have been listed,” he said.

Partnership required

USFWS estimates that 80% of threatened and endangered species depend on private land for all or some of their habitat. Scientists increasingly find that endangered species’ odds of survival are linked not just to the existence of their habitat, but to its active stewardship.

“There’s a reason these critters are here on this earth. And so, when they start disappearing. I’m thinking: how long before me? A lot of these things, we don’t know how they fit into these systems,” Kolb said.

It could feel unimportant – a strain of fish, or one kind of bird. But for White, Kolb, Davies, Haarmann and a multitude of other landowners and managers, we go the way those species do, and what’s good for those species, done through collaboration and flexible, informed management, is good for the long-term viability of working lands, and for the rest of us.

“You know, this land used to be all one continuous track. Native people didn’t have these separations. Critters don’t pay any attention to these lines. They keep on moving. They know where they’re supposed to go. It’s genetic memory that makes them migrate through these areas. Just so happens, some folks made it public. Some folks made it private,” Kolb continued. “But everybody plays a role in this because with everybody working together, public and private is a continuation. That is landscape scale. And that’s what we all should be striving for.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Pingback: The Fish & The Flame – On Land