Completing the Conservation Finance Picture in the West with Lesli Allison

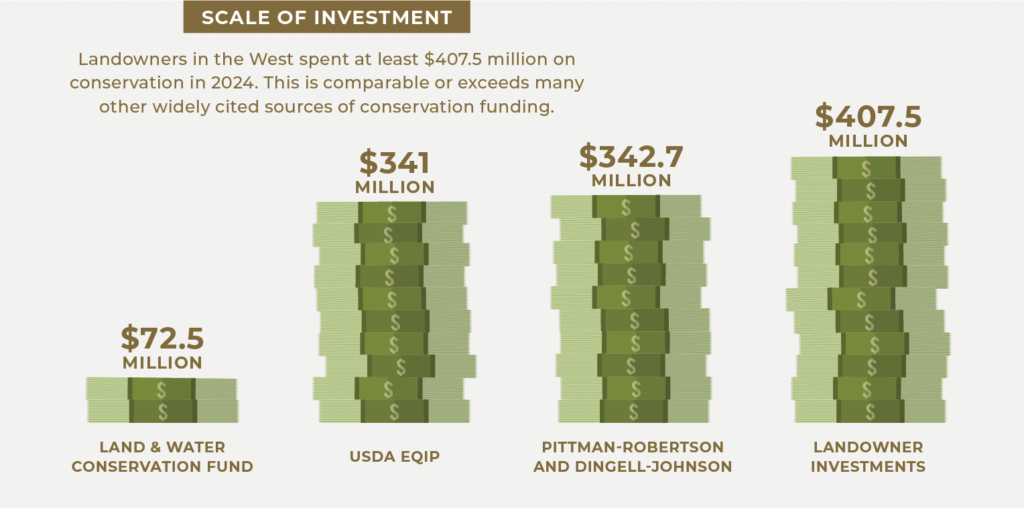

A new report reveals that Western landowners invested at least $407.5 million of their own money in conservation in 2024, outpacing many of the most well-known public funding programs. This new data fills a major gap in how we understand conservation economics.

Today, WLA CEO Lesli Allison and WLA’s communications director Louis Wertz walk through what the data shows, why these investments have gone largely unrecognized, and what it means for the future of conservation in the West.

Full report here: https://westernlandowners.org/landowner-investment/

listen

Links from this episode

Explore the report: The Scale of Landowner Investments in Conservation Across the American West

View the press release: Groundbreaking report reveals scale of private landowner investments in conservation

Learn about Southwick Associates the market research and economics firm

episode transcript

[00:00:00] Louis: Hello and welcome to the On Land Podcast. I’m Louis Wertz, the editor in chief of On Land and Communications Director with Western Landowners Alliance, and I’m delighted to be joined today by a familiar voice on the podcast, Lesli Allison, Western Landowners Alliance’s CEO. She’s here today to talk with me about a new report we just published titled The Scale of Landowner Investments in Conservation across the American West. And that seeks to answer a basic but often overlooked question. How much are landowners already investing out of their own pockets to care for land, water, and wildlife? Lesli, let’s start there. Why is that an important question and to whom?

[00:00:39] Lesli: Well, it’s an important question because private lands are vital. They’re vital to all of us. They produce habitat, clean water, energy, open space, not to mention food, fiber, energy, all the things that we all rely on for our own survival. And private Landowners are doing a lot more than just enjoying these places.

They’re caring for them, and in many cases, they’re restoring and improving them. We have Landowners reintroducing native species, rebuilding soil carbon, uh, recovering after wildfire and pest infestations, adapting to climate change and so much more. And so. How much Landowners are investing in conservation should be an important question for anyone who cares about the future of the West, and its people and its wildlife.

And, and by the way, private lands are nearly 50% of the west and the majority of land in the lower 48 in the United States. So it’s, it’s a very important topic.

[00:01:40] Louis: So what did we find?

[00:01:42] Lesli: Well, I think what’s so striking about the report is that it really makes visible the scale of private landowner investment in conservation across the American West. They’re investing in a massive scale, $407.5 million in 2024 alone. In conservation practices, and that’s over and above anything that they’re doing, uh, in the course of production or, you know, other income generating activities.

So this is out of pocket investments in conservation, and the acreage investment works out to be about $5 and 18 cents per acre. But that investment isn’t just spread willy-nilly across every acre. It’s actually targeted by the people who live. Work in these landscapes every day and, and care deeply about them.

They’re in a very good position to, to make the most cost effective conservation investments. And they’re investing in things like range improvements, right? The range, improving our range lands in our forests, reducing wildland fire risks and improving water resources and riparian habitats.

And it’s important because these investments directly support things like wildlife migration, corridors, water quality, and landscape resilience. Another thing that people may not think about that often is that private lands provide connectivity between public lands. Uh, and this is really important for wildlife migrations of animals large and small.

And, and I think Louis, the findings just really help us reframe conservation funding, conversations by showing that Landowners are not passive beneficiaries of programs. They are lead investors and frontline stewards.

[00:03:30] Louis: Well, nearly $408 million sounds like a big number. But, you know, context is key here. How does it compare to other sources of funding for conservation and, you know, are Landowners even in the ballpark with. Feds or sportsmen or other other folks who consistently invest in conservation?

[00:03:49] Lesli: Well, that’s another really interesting thing that jumps out from the study. landowner investment spending exceeds some of our most notable federal funding programs in these same states. For example, in the same 11 Western states, it exceeds the income, the program funding through the Pitman Robertson and Dingle Johnson programs. Those are excise taxes on, on firearms and phishing tackles, uh, you know, often and, well attributed to an important role in conserving our wildlife across the west and across the country. Um, but the landowner spending actually exceeds, that resource.

Similarly, USDA, US Department of Agriculture has a program called equip. It’s a cost share program, very important, large, funding source and. In 2024, landowner investments in conservation actually exceeded the USDA’s equip obligations that similarly, by quite a bit exceeded the funding investment from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the Stateside Assistance Fund.

And we’ll talk about this, I hope a little later, is that this study doesn’t capture the cumulative landowner investments in conservation.

So it just captures one aspect of landowner contributions and that that investment that we’ve captured here is on par or exceeds some of the most well known. Sources of conservation in the American West.

Louis: I can hear the skeptics out there wondering how we up with figures. we don’t wanna be cynical about the figures, but skepticism is warranted. When you have a new report come out. Can you help people understand the process, how the survey analysis were done, you know, what we went through to try to make sure that this was as rigorous as possible.

Lesli: Absolutely. So we, we started out just with this basic question, how much are Landowners actually investing out of their own pocket in conservation? And we wanted that answer to come. from a reputable, firm. We reached out to Southwick Associates. They do a lot of the studies for state wildlife agencies and others.

and that’s who we were able to contract for the study and relied very much on their expertise, in national polling and economic data research, uh, to understand how to do this.

what we did was we sent, uh, surveys out all over the place. we try to get it out as broadly as possible. And at the end of the day, we had 649 qualified surveys. from Landowners who own 500 acres or more in six Western states, and the survey focused on out-of-pocket conservation spending, beyond normal operating costs. And then what Southwick did, is that they, helped us extrapolate those responses across the west.

The results were statistically weighted to estimate regional investment levels across all 11 Western states.

[00:06:41] Louis: So when I heard we were surveying only Landowners with more than 500 acres, which is an important caveat here, I was a little worried because I know we have a lot of very active members, um, who own less than 500 acres, and that’s a huge group of Landowners just in general, that, uh, might be making conservation investments.

Can you explain a little bit why that decision was made, and do you think that means we’ve undercounted the scope of landowner investment?

I know you are actually a landowner. very invested in conservation of less than 500 acres, just barely so, so it, it even excluded you.

[00:07:16] Lesli: It did exclude me. Dang it. Um, and that, and that was kind of the response of a lot of Landowners. Why didn’t you count us? You know? And of course we would’ve loved to have counted every acre, every quarter of acre. Um, but you know, the reality is it’s really a cost and data management issue. There’s a lot of Landowners out there.

And it was just unmanageable. And so we just had to draw a line somewhere that made sense for us, uh, within our budget, within studies scope. And so we, we drew that line at 500 acres and yes, it leaves out a lot of people. And I think that that, obviously means that the Landowners are investing a lot more than the $400 million that we were able to capture, with the survey that we did.

And, um, we also, you know, looked around to see what other surveys had had come up with, uh, some that had in smaller regional areas that surveyed Landowners with smaller acreages. Um, and, and we found some similarities across these studies, large or small Landowners, different regions. Uh, one of the common themes is that conservation is a core landowner priority.

And in our study, most surveyed Landowners rank conservation as a top management priority. It’s in the top three for Landowners and their investments are driven by stewardship values, long-term land health, and a sense of responsibility to. Future generations. And that’s just something I hear all the time in my work with Landowners.

I’ve been doing this for 30 years and I hear over and over again from Landowners that they are trying to make the world a better place on their piece of land in their community with the resources that they have. They’re trying to make things better. and you know, it’s interesting in terms of, large and small Landowners and how much they’re contributing.

There was a study in Oklahoma that pulled, a sample of all private Landowners regardless of acreage, and the conservation spending was actually higher per acre, the fewer acres someone owned. And, and I think to me that makes sense in an economy of scale kind of way. Um, and also because, I think size can be a limiting factor when you have a, you know, very large operation to manage.

It’s, you know, time and money. it takes a lot to span a huge number of acres. but I think that what matters about that is that Landowners care, no matter whether they have small parcels or large parcels, and this underscores the opportunity for voluntary and partnership based approaches to conservation.

And I think the study just really reveals, and it’s backed by these other studies, that Landowners are some of our most willing and committed conservation partners.

[00:09:59] Louis: Oh, that brings me back to a couple of

clarifying questions I had when we were digging into the data that we got back from Southwick. does that $407.5 million figure include the cost of purchase land? and then what about opportunity costs?

[00:10:12] Lesli: So, um, the 407.5 million does not include the cost to purchase land, and that’s an enormous figure as you can imagine. Not just the purchase price, but then the financing of that and the ownership costs that we also did not include. Uh, things like property taxes, insurance, labor, infrastructure, all that, that actually has to underpin the conservation.

Um, we did ask about opportunity costs in the study. Um, the, and that is the cost of not doing something would be bad for the environment, for example. Um, and, uh, we found that, you know, 59% of respondents did give up income generating opportunities to benefit conservation. And some of the things that they’ll give up, for example, is agricultural expansion or residential commercial development or recreation or access based income.

And while many of those losses Landowners reported were under $50,000, or those opportunity costs, one in five actually exceeded a million dollars. Um, and I wanna just touch briefly too, another thing that the, the study did not ask about. Was property tax. farmers and ranches nationwide contribute

$9 billion in property taxes every single year. And those things support all kinds of services in our local communities. School, buses, roads, you name it. Um, really important part of the picture that often never gets discussed and can be a, a very significant cost annually for the landowner.

[00:11:49] Louis: So another aspect of this that comes to mind for me and that we deal with all the time in, in various ways that through our programming at Western Land Alliance is the cost that wildlife actually, come with when you, when you create more habitat for wildlife. it can bring additional costs and, and usually it does, frankly.

did we measure that in the survey? What, what did we hear from people about, about that aspect of this? And then, you know, what does that point to for, um, how, we might, use this data?

[00:12:23] Lesli: Well first off, I don’t know any landowner who doesn’t appreciate wildlife. I think all of us love wildlife. All of us wanna see the wildlife continue on. Um, and yet, you know, hosting wildlife on your property, if you’ve got a lot of wildlife on your property, that can come with some very significant economic impacts.

And elk is a, is a great example in the west. Elk are great at knocking down fences. They’re pretty good at consuming your haystacks that you might have needed for winter feed. They compete with livestock for forage. They often bring in a trail of noxious weeds with them and predators, in some cases, um, in some parts of the country, they, they come in with Bruce Osis, which can, you know, really put people in a tough position financially.

and in the Southwest water, uh, supplying water to livestock and wildlife, it can be costly. So there’s some very, uh, big costs to having wildlife on your land. As much as we love them, those costs are very real. And, you know, some states, um, and, and there’s some federal programming that offers some compensation for that.

But in the study, Landowners reported $101 million in losses to crops, forage water, and wildlife. They reported another $37.6 million in the costs of repairing those damages, and only 16% of the Landowners surveyed. Actually received any compensation for those things. And those that did receive compensation only received 20% of the total loss on average.

So what this tells us is that Landowners are absorbing the majority of costs associating with supporting public wildlife and these opportunity costs in the wildlife damage bills are rarely counted. Uh, meaning that the landowner, total landowner conservation contributions are actually significantly understated even by our own $407.5 million figure.

[00:14:19] Louis: so we’re, we’re talking about sort of a, a minimum, it sounds like a 407 and a half million dollars, of investment. Out of pocket. And then there’s all of these costs on top of that. And then plus there’s all of the required costs, what we were measuring here was, just voluntary spending.

there’s maybe even a challenge there that underscores like why this has been so difficult to measure and, and maybe, you know, has escaped measurement by universities or public agencies for so long.

Is that how difficult is it to disentangle that for a lot of land? You manage a large ranch for a long time and like, what’s normal operating versus conservation spending? it seems to me like that would be pretty tough to disentangle for a lot of Landowners.

[00:14:59] Lesli: Yeah, that’s a great question, Louis. And it is. It can be very tough to disentangle that. So for example, if you’re managing livestock in a way that is improving soil health and improving your rangeland productivity. You know, theoretically that’s gonna be good for your livestock. It’ll help sustain your production, keep your numbers high in times of drought, things like that.

So you can make the case that that’s just something you’re doing for your own, uh, benefit as a producer. And so it is hard differentiate that from things that you’re doing specifically for, you know, land health, uh, and for wildlife habitat. And so what we’re asking Landowners to try to tease out is.

Let’s say that you do that grazing management, but part of that grazing management might be to, uh, exclude livestock from certain areas for certain parts of the year, like a riparian area or where there’s pollinator habitats or something like that. So that, that is specifically to benefit wildlife or the resource over and above what you’re doing for your own production Right? And if you’re restoring a forest, you might be selling some timber out of that, but from my experience, managing a ranch, the sale of the timber. Wasn’t contributing to our bottom line. We used the sale of any of the commercial timber. We were able to harvest. To pay for the much more expensive restoration of the ecology of that forested ecosystem.

So we were trying to do watershed, forest health restoration most of the time that was thinning, uh, non-marketable timber, doing prescribed fire, all those things that are at our cost. And if we could sell a few trees. A load or two of logs that help pay for all that restoration. Great. And we would consider that, for example, an investment in conservation rather than something that

we’re doing for our own, um, you know, income generating purposes.

[00:16:49] Louis: So big picture. now that we’ve gone through what the data told us in the study, if Landowners are, are investing at minimum $400 million a year just in the 11 Western states, how should we be thinking about conservation if, if we’re, now that we’ve got a fuller picture of who’s actually spending on it.

[00:17:09] Lesli: Well, I think that the central takeaway here is that Landowners are, are pivotal. they are central, not peripheral to conservation in the west and elsewhere. And we need to have, first off. Approaches to Landowners that recognize that we need to be engaging Landowners first and foremost as partners, as primary investors in conservation.

Uh, building out those partnerships, finding ways to, um, leverage and augment those investments and to align public and private interests at every opportunity. Um, it, it’s, you know, a lot of people talk about, uh, these supporting Landowners supporting conservation on private lands as a subsidy. It’s, it’s actually an investment

in the resources that all of us need. many of which are not marketable, they’re not sellable at this point in time. So it’s, it’s our way of partnering and co-investing in ensuring that the things that we all care about and that we all depend on are here both for us and for future generations and future wildlife.

Um, so I think it’s, it’s really just a, a, a rethinking of who Landowners are in the constellation of conservation players in the country in a way that gets us to better outcomes.

[00:18:46] Louis: I think maybe a good way to close is to ask a question that’s, it’s pretty open-ended here, but, what are some of the signals from this study about how we might think about the US economy and the conservation economy together, because I think part of the thing that’s mind opening about this for me is that we haven’t appreciated that private citizens would be making such large voluntary investments in nature. And then it also seems like the sort of thing that we want as much of as we can, but we can’t ask people to spend money they don’t have. So how are we gonna solve those problems?

how do we better align. The, macro economy, the, the economy with conservation outcomes.

[00:19:44] Lesli: Yeah, I think that’s the question of our day actually. I think that’s the, that’s the question. I think the mistake that the conservation movement has made in this country for, for all the way back to inception, really is separating. Uh, this question of conservation from the question of economics.

And you, we had a rancher at one time that said, you, you can’t expect ranchers to operate outside of capitalism, right? We live in a capitalist system, but for some reason nature isn’t in play, right? And we don’t, we don’t take the cost of caring for nature into account in our economic system. When you go to the farmer’s market, you’re gonna buy.

Meat or you’re gonna buy vegetables, you might buy cut flowers, but you’re probably not buying wildlife habitat stewardship, right? You’re not paying for the care that we’re asking people to take. On these landscapes, and you know, a lot of people say, well, isn’t that just the cost of doing business? If you’re, if you’re a landowner, well, to some extent, yes, but it’s enormously expensive to own.

Manage care for conserve, restore these places, and when those costs exceed your ability to pay for them when they’re, when they make it so that it’s not economically viable. To keep that piece of land intact or healthy, then what we get is degradation or or conversion to something else that is less compatible with conservation.

So we have to make it economically viable for people to steward these lands, to keep them intact and to steward them. That means people need to be able to generate a reasonable livelihood, reasonable income. Not only producing products that we can consume immediately, like, like, like food, but caring for nature and all of the products and services that nature provides.

That right now you don’t buy when you go to the, the local grocery store or the hardware store. And that’s where we need to do a better job of integrating stewardship and economics. And, you know, there are ways to do that. We’ve been working on a program, uh, that we call Habitat Leasing, which provides an annual payment for people who are managing, working lands in a way that not only supports the agricultural production, but is also ensuring that there’s good habitat and forage.

For wildlife that also needs to be there. And that way you can integrate the caring for nature with agricultural livelihoods and diversify your land management. And then, then you have a win-win situation. When we go the other direction, and we try to do it strictly through regulation and we impose more and more regulations to try to save the things that we care about, but are unwilling to pay for.

That puts negative economic pressure on lands that are already at risk, right? It drives lands into development, drives them into other kinds of more profitable land uses. It makes it impossible for us to actually care for these places. And so I think that’s what this study underscores is that we all care about conservation.

You can see in the study, 65% of the Landowners say that the cost is what limits their further conservation investment. They’re also very concerned about loss of management control. Regulatory misalignment, like Landowners shouldn’t be punished by more regulation. If they’re doing something to restore, threaten, and endangered species, for example, they should be supported, rewarded, recognized for that, right?

Lost income opportunities if you move your livestock off of an area to protect some kind of a wildlife habitat. How do you make up for that income so that you can continue to stay on that land? Right? And these are the kinds of things. And then we, we just don’t have enough technical assistance that shows up in the report as well.

So these are the areas that we need to focus in on to better support and, leverage these conservation investments from a landowner. Communities clearly has a strong land ethic and wants to do it.

[00:23:46] Lesli: I really hope that this study can be seen for what it is. It’s an insight into people who are managing lands throughout our country who care a lot about the resources in the same way that the public cares about them, and that is an opportunity.

For us to find a better, less divisive path forward. And it doesn’t really matter how much money someone does or does not have. On a piece of land, what we need is for people to be caring for these resources. We need the public’s participation in that. We need it to be done in a way that aligns, rather than divides interests.

Uh, in, in short, working with and not against the people on the land is where we can and must go if we’re going to be successful. Well, hopefully this study will help open up more of those possibilities.

[00:24:40] Louis: Awesome. Well, it’s always a pleasure talking with you, Lesli, and I really appreciate you sharing, um, your insight. it brings a lot of value to the report. and people can find that report at Western Landowners dot org slash landowner hyphen investment.

Um, and we will have all of that information on our website as well. Thank you so much for joining me today, Lesli, and we will, I’m sure be talking again shortly.

[00:25:06] Lesli: Thank you very much Louis.

credits

On Land is a production of Western Landowners Alliance, a West-wide organization of landowners, natural resource managers and partners dedicated to keeping working lands whole and healthy for the benefit of people and wildlife. This episode was hosted and produced by Louis Wertz and edited by me, Zach Altman.