Heated Negotiations and the Future of Western Water

Things were heated at the Colorado River Water Users Association (CRWUA) Annual Conference this year, the largest meeting of water managers in the Colorado River Basin. This year’s meeting was especially important and tense because the guidelines that govern the operation of the Bureau of Reclamation’s (BoR) facilities on the Colorado River expire at the end of 2026. The basin is facing a large water shortage, potentially up to 4 million-acre-feet, and the new guidelines will determine how that shortage is distributed in dry years. While the BoR has encouraged the basin states to come to a unanimous agreement, the Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) and Lower Basin (Arizona, California and Nevada) are at an impasse.

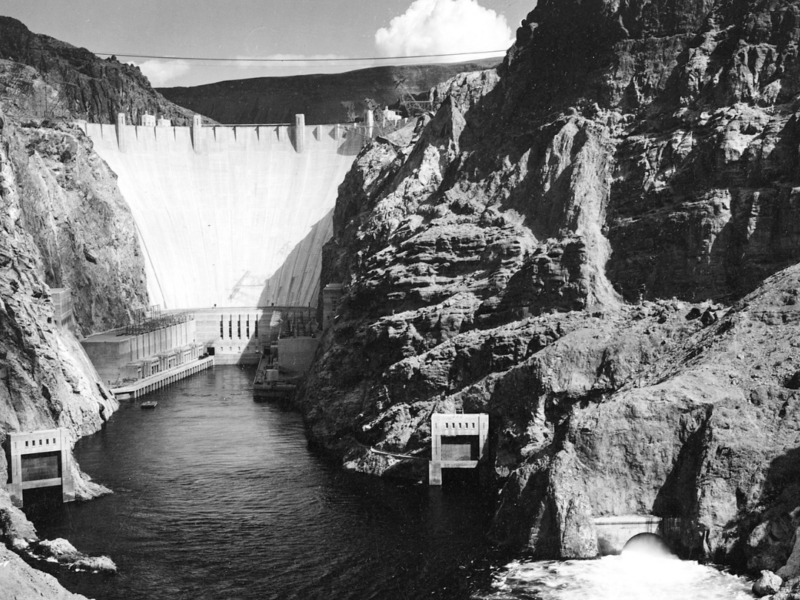

Both the Upper and Lower Basins have proposed their own alternatives for how the system might operate in times of shortage, but it seems unlikely the Bureau of Reclamation will fully adopt either proposal. Instead, the BoR presented their alternatives at the annual CRWUA conference, which included a hybrid of the two proposals. They also modeled other proposed alternatives and will continue to refine all of the options as they develop the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) that will guide governance on the Colorado River after 2026. Many questions remain unanswered, from who will take cuts and how facilities are operated to how water accounting is performed. Even what facilities are included in the guidance is up for debate. Will dam releases be determined based on the full system contents including the Colorado River Storage Project dams in the Upper Basin, or only the contents of Lakes Powell and Mead?

Often, these processes feel remote and opaque to producers on the ground, but the outcome of these negotiations will have significant impacts on the entire Colorado River Basin in the coming years. Each alternative presents a different vision for how water cuts will be distributed throughout the basin, but the consistent baseline for all of these negotiations is preparation for additional water use reductions. Parties are trying to find a way to equitably share those reductions.

“It’s becoming clearer than ever that producers and the agriculture industry across the basin states will be forced to bear the brunt of these shortages. The uncertainties of future hydrological conditions mean it’s critical that groups like Western Landowners Alliance continue to advocate for the policies and opportunities informed by those most impacted by the outcomes of these negotiations,” explained Traci Bruckner, WLA’s Chief Policy Officer.

Despite the ongoing negotiations and the looming threat of litigation, it is possible to preemptively adapt to drying watershed conditions while we await final operating guidelines and what shortage distribution may look like if the future continues to dry. Producers on the ground are already taking significant steps to build drought resiliency into their operations, including things such as process based restoration and alternative forage crop experimentation. As we all learn more about what methods work in what areas, we all continue to learn from each other and adapt to create a more resilient river basin. Every sub-watershed is different, and adaptation will look different in every area.

“As we head into 2025,” says Morgan Wagoner, WLA’s Western Water Program Director, “we will continue to share information on water in the West and provide resources to support landowners on the ground. We’ll also be working directly with producers to understand what works and what doesn’t, and share that information with landowners and water managers. WLA will continue to work with partners throughout the basin to advocate for water management policies that work for landowners and producers on the ground, and inform landowners of ongoing negotiations and water management developments throughout the basin.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Reyes Garcia

It’s so encouraging to know that Traci and Morgan are so deeply involved, given their deep knowledge of so many of the difficult issues that need to be definitively resolved.