Breathing Life Into Bronze

What matters to Montana’s master wildlife sculptor.

Kelly Bennett and Carolyn Quan, in conversation with Tim Shinabarger

Right: Sculptor Tim Shinabarger takes a break on a backcountry pack trip.

Kelly Bennett and Carolyn Quan (KBCQ): Why don’t we start with your background, growing up in Montana?

Tim Shinabarger (TS): I was born in Great Falls so from an early age, was exposed to Charlie Russell. My parents would take me to the museum and up to the cabin as a little kid, so I was always in love with Western art. We lived all over central Montana so the landscapes and nature and wildlife were always very present in my life.

KBCQ: How did you find your way to sculpture?

TS: When I was about 10, I started doing taxidermy. My first piece was a terrible little sharp-tailed grouse. I read a book about Robert Rockwell, who was a museum taxidermist at the American Museum of Natural History, and that led to reading other books about leading taxidermists who were also members of the Boone and Crocket Club. By the time I was in high school, I had a thriving business going in my parents’ basement and did taxidermy all through college. The only time I worked for anybody else was in college when I worked for my dad for a few years in construction and for the BLM and Forest Service. I also worked as a guide down in Gardiner [Montana] for about six years. Other than that, I’ve never held a job.

The taxidermy naturally led me into painting and sculpting. I used to paint just as much as I sculpted up until about 1999. By the end of the ‘90s, my sculpture was really taking off and I was spending a lot of time at the foundry so it was too much to paint, too. For about 25 years, I’ve just focused on sculpture, but now I’m actually transitioning to back doing some more painting.

KBCQ: You have a deep connection with wild landscapes and wildlife – how did it come to be?

TS: When I was about 13, my dad took me on a full-blown pack trip into the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness. It was my first elk hunt in the wilderness and we went out for 10 days with horses and mules. It lit the fire in me. I’ve been hooked on those kinds of trips ever since. They have taken me all over the West, clear up to Alaska, sometimes on horses, sometimes with just a backpack. My art has always been inspired by actual experiences out in the wild and I have done a lot of drawings, photography, videos and painting from life out on these trips. We try to get out into the landscape every fall.

KBCQ: You’ve mentioned other artists who have influenced your career over the years. How has that mentorship affected your journey as a professional artist?

TS: Way back in those early days in Billings, I was fortunate to meet artists who knew the greats like Clyde Aspevig and Hollis Williford so I had really great mentorship right from the beginning. I got to paint with Clyde in my early 20s and spent a lot of time with Hollis, who really put me on the right track. He taught me how drawing is the foundation for all art and was the strongest influence on me. I was incredibly fortunate to be at the right place, at the right time, learning from people like Jim Reynolds and Bob Kuhn and many other top artists. I never went to art school – I have a degree in business – and the art classes I took were very modern, non-objective stuff and I didn’t think I got much out of it. These mentors really helped me become the artist I am.

KBCQ: Would you elaborate on the concept that drawing is the basis for all great art? How does drawing relate to sculpting?

TS: Hollis taught me that the thought process between drawing and sculpting is the same: you are trying to capture the form and light. With drawing, you think in black and white and line. It is about accents, highlights and middle tones. Well, that transfers directly to sculpture. You’re getting the form, but you’re also thinking about the play of light. You may gouge the clay a little deeper to create a darker area, like the recess behind a horse’s shoulder. You may smooth an area that you want to shine and highlight, like the area up on a horse’s rump. You are thinking about how texture absorbs light while smoothness reflects it. It is a kind of calligraphy you constantly work in – how to take clay and give it the illusion of the play of light on the piece to bring life to the sculpture. You are thinking the same thoughts with pencil or with painting. What can I do to create that illusion? The hardness of rock, the softness of fur, the textural feeling of foliage. Hollis taught me that way of thinking and you see a lot of this same thought process in Clyde’s work. When you’re painting, you’re thinking about color; when you sculpt, you’re thinking about patinas and the foundry process. There are different specialties you have to learn, but the thought process is the same.

In my art, I have to think about the softness of muscle, compared to the hardness of bone. When you draw, you record all of this and it transitions right into sculpting or painting. If you are a good draftsman, you’re probably going to be a good sculptor or painter. People often think you’re either good at one or the other, but Hollis taught me that if you’re good at one you should be good at the other, too.

KBCQ: How do you choose what you are going to sculpt and how you compose it?

TS: Generally, it’s something I’ve seen. I’ll go on a pack trip and see an elk do something interesting, but then I have to make it art. You may see a really neat gesture, but have to create a sculpture that looks good from 360 degrees, so I’m thinking about design and negative space. I’m always gathering references of skeletons and bones, anything that helps inform understanding of the subject. I’ll take you through a piece I recently did:

I’ve always wanted to spend time in the Wrangell-St. Elias, our country’s largest national park. It’s really well known for Dall Sheep. I booked a hunt but asked to come up 10 days early to paint and they dropped us off in the middle of nowhere. I spent 21 days out in the field in country that is just beyond comprehension, beyond spectacular. I was struck by the massive, vertical headwalls and rugged landscape. And also, by the animals that live there. I got to know the family that owned the lodge there and they happened to be very into art. The matriarch thought it would be nice to have a large sculpture in their garden and as we thought about it, the Dall Sheep stood out as an iconic species in that landscape. Because the country is so vertical, I wanted to do something up high on a rock that felt very vertical. The whole idea was to capture this iconic species in a way that speaks to the environment where it lives. I just installed it this spring.

Sometimes the idea is collaborative with a client, but most of the time it’s something I’ve seen. Bison bellowing when they are rutting in Yellowstone Park, a warthog flagging and running with its tail up, a bull elk bugling, a grizzly striding – these are just incredible things to see and translate to sculpture.

KBCQ: What draws people to your art?

TS: People have said they felt like my pieces feel like a real animal, in a real place, at a real time. I think that’s something I’m very conscious of. I want to make the animal soft and supple and life-like, yet capture the play of light. I’m not worried about doing the detail of hair and overdo things; rather I want to capture that feeling. Bronze is a hard, sterile medium and the hardest part is breathing life into a sculpture. I think that is what resonates.

KBCQ: Having grown up in Montana and seeing a lot of change over the years, what does stewardship mean for you and how has it changed over the years? Does it affect your art?

TS: I believe there is a lot of science to prove that active management can be so important to these landscapes. One thing I can point to easily is in places where we have fought fire so much and the forests have gotten so old. We have dealt with the pine beetle infestation in these forests and now, the downfall is horrible. It’s almost impossible to get through some of them with horses. Even wilderness needs some management. I think we have messed that up a bit. As an artist, it makes it harder to get to these places. We have more fires and the Forest Service has put so many resources into firefighting that the trails are not well maintained. I was the Wilderness Ranger for two years out in the Gardiner district and there are trails that are almost grassed over now because people aren’t using them because there isn’t money to keep them maintained. It’s unfortunate. On the Thoroughfare, you basically can’t get off the trail and the downfall is over your head. These are trees that probably should have burned naturally sometime in the last 100 years. It also all changes where the animals are.

I’ve seen lots of people move into Montana. I see more ranches that are conservation- and stewardship-minded. When I was younger, there was a lot of logging and mining and building roads everywhere. Now ranchers seem more thoughtful. New people and changing values require a lot of education. In Bozeman, it just kills me – my foundry was in Bozeman so I’ve spent the last 25 years driving there. There was not a speck of knapweed on that highway when I was young. Now, it is just crawling up the hillsides and the people don’t talk about it at all, even though it’s such a cancer growing and invading the area. They don’t know they need to talk about it. They talk about things like protecting wolves or trails, all while this invasive weed is taking over the whole county… and affects wildlife and ranching! It’s even in the forests now. Landowners are the only ones talking about these kinds of things and I feel like there is a lot money going in the wrong places that could have real impact.

KBCQ: How can art help facilitate that dialogue and address that educational challenge?

TS: I tend to work in the positive. I want to show wildlife in an inspirational way. I’ll donate pieces to auctions, like for Boone and Crockett. I want to connect with people and show them the inspirational side of wildlands and ranch lands. When it comes to who collects my work, I think the ranchers tend to have a better sense of the importance of managing these landscapes. I wish I could help people understand that we can’t just “leave them alone.”

It’s important not to sit around and wring your hands and complain that everything has gone to pot. You can get a lot done when you focus on opportunities to effect change and actually do things that have impact. These groups that litigate and talk about everything that’s wrong often never actually do anything. I love that I see more groups coming together, welcoming different kinds of people and focusing on the good.

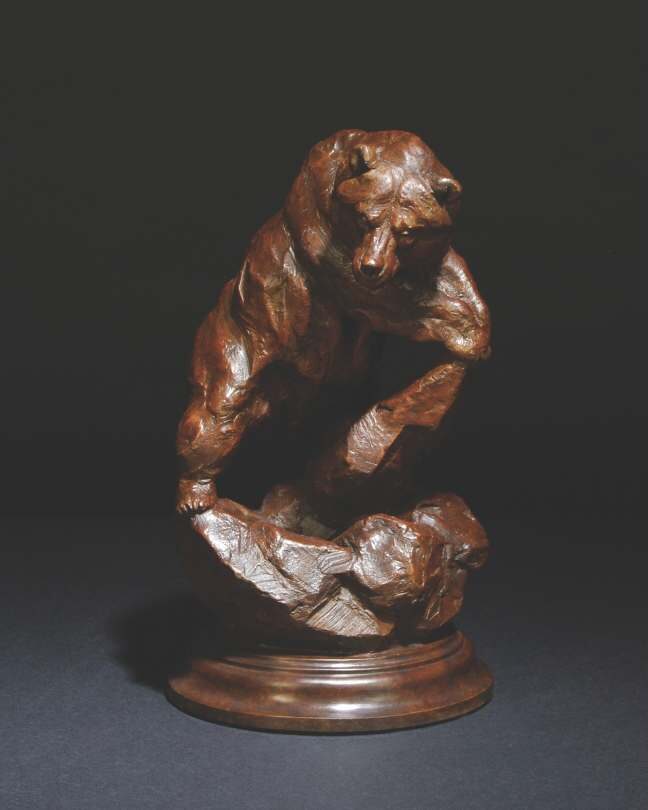

Right: THOR

Tim Shinabarger