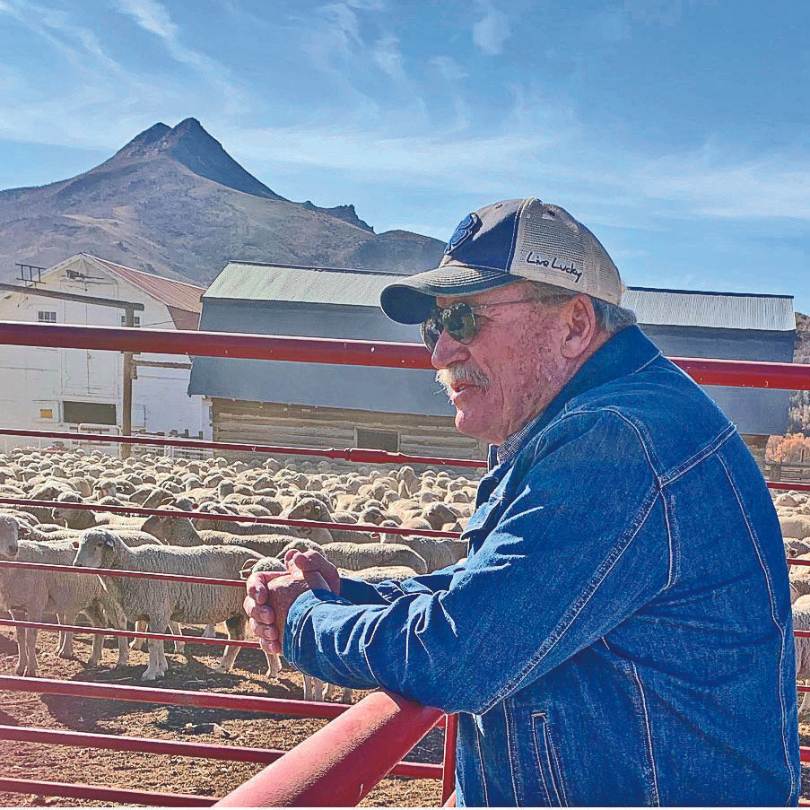

Pat O’Toole, Remembered

Pat O’Toole was a leading voice in the West for both agriculture and conservation. With Pat’s passing in February of this year, we reached out to George N. Wallace, a friend of Pat’s for over 50 years, for a remembrance.

I met Pat O’Toole in the early 1970s while visiting my alma mater, Colorado State University (CSU). He was a lean distance runner from Florida, majoring in philosophy. In between homework in Logic and the Scientific Method, Ethics and Epistemology, he found time to court the rancher’s daughter, Sharon Salisbury, who would become his wife, mother of his children, ranch partner and lifelong companion. That romance set the direction for an unexpected and remarkable life.

At CSU, Pat was engaged in discussions about the great ideas coursing through the history of Western Philosophy, wondering which ones we might draw on to help us navigate the times. And he worked on the CSU student newspaper, writing regularly about all the contemporary issues that characterized that turbulent period. In retrospect, I think that this classic liberal arts education served Pat well as he went on to become a successful rancher, father, grandfather, legislator and champion for ranchers and farmers who steward land and water in the arid West.

Pat O’Toole became a successful rancher, father, grandfather, legislator and champion for ranchers and farmers who steward land and water in the arid West.

Those years helped fuel the broad thinking, passion, commitment and leadership that we all benefited from and will sorely miss as a result of Pat’s passing. Issues of social justice, free markets versus the collective good, resource sustainability, ecological health and biodiversity, and what led to proper governance for all this, were always rolling around in his unstoppable mind. There, they were blended and tempered by the practical challenges of land, livestock, drought, hard winters, fickle markets, labor shortages, working with state and federal land managers across different administrations, generational transfers of responsibility and much more. He acquired a hybrid vigor from it all.

Of course, it was Sharon, the Ladder Ranch and its people, livestock, land and water management challenges that planted Pat’s feet firmly on the ground and along the stream bank—but he could always see the world from 30,000 feet.

This uncommon mix of practical knowledge and broad thinking fueled Pat’s passion, commitment and leadership. It could be seen in a variety of places. I remember it from the cookhouse table, where Pat and Sharon would take breakfast with the hands and guests while giving an overview of the things that needed to be done that day: first in “Spanglish” to the hands and herders, and then again to any English-only visitors present. It showed up in the Wyoming Statehouse; in hearing rooms in Washington, DC; in the board meetings of the Family Farm Alliance and in all of the wide range of other venues where Pat was regularly on the agenda.

Pat saw that agriculture would require more support from the majority. Instead of acting defensively against bad policy and regulation, the agriculture community needed to recognize the legitimate interests of those who loved open space, wildlife, clean water and healthy food, as well as those who just wanted to hike, hunt, fish, ride and get away from it all.

Pat earned his spurs the hard way, coming as he had to the West as an outsider. There were some tests. He and Sharon lived for a good time in a cabin without water or electricity and spent time in remote sheep camps in the summer. Pat had to learn the lay of a large ranch landscape that stretched across the Colorado-Wyoming line and from high-elevation forests down to the Red Desert and Powder Wash country. He had to learn a complex matrix of deeded land, leases and public land grazing allotments.

Through it all, he earned the trust of the family (it helps if you provide grandkids) and developed a deep sense of place and affection for the ranch. It became his base and his hard-earned competence won him respect from peers. Even before he became a successful rancher, he was involved with issues affecting a larger West as well as the 2% of the U.S. population that produce our food and fiber. But, with a philosopher’s concern for the greater good, he also cared about the other 98% more than many, and so he gravitated toward public and volunteer service to form lines of communication across what we sometimes refer to as the rural-urban or the red-blue divide.

Pat saw that agriculture would require more support from the majority. Instead of acting defensively against bad policy and regulation, it needed to recognize the legitimate needs of those who loved open space, wildlife, clean water and healthy food, as well as those who just wanted to hike, hunt, fish, ride and get away from it all. Such people could be the ones willing to support the policies and programs that saw value in working landscapes. Like the Western Landowners Alliance has done, he thought it more important to feature farmers and livestock producers who envisioned and worked for a sustainable future and to reveal what they were providing.

The O’Toole’s cattle graze in an early spring seasonal wetland on the Ladder Ranch, while happy ducks feed in the foreground. Photo by Pat O’Toole.

The Salisbury/O’Toole’s have always welcomed new ideas and people from all walks of life and around the world to the ranch. It is always busy there. Most visitors are sort of naturally absorbed into the pleasant chaos of many moving parts. Kids, dogs, herders, cowboys, cooks, interns and livestock are all doing something, headed somewhere. You have to step over boots with spurs still on them, piles of ranch documents, hats, coats, books and magazines and more books, which were still holding their ground alongside the cable news playing in the living room. As if a large ranch and family wasn’t enough to dwell on, Pat’s reading included a range of topics and historical periods. He worried and cared about the wider world. His life demonstrated that enlightened leaders impart such caring as a prerequisite.

It is hard to remember Pat without including Sharon. She is a poet, partner, rancher, matron, writer, mother and grandmother of children who will carry on a vibrant and positive legacy. She is involved in many of the same things Pat was. They were always a team, and it was hard to detect who was the owner of a given project or idea. But isn’t that the way it should be?

Having my own chores to do, I followed Pat and his busy life indirectly over many years. We visited each other’s places and talked periodically on the phone. Talk turned first to family, the weather, the ranch and our farm, but soon we got around to the broader ag land and water issues and policy formation that we were both involved in. Like Plato and Socrates must have enjoyed their walks in the garden, I enjoyed our conversations. Pat’s caring, commitment and effort to model stewardship and lead on issues reinforced my own more local efforts. Western agriculture needs leaders who think broadly, who care about the world and who are not so reactive to opposing views that they won’t look for shared values. Pat’s example encourages those of us who, despite the odds, continue to work on ways to minimize the loss of ag land and water along Colorado’s Front Range, and to communicate more carefully with people not involved in agriculture.

Pat was not done. With the kids doing more to run the ranch, he had some energy left to help form a coalition to address issues affecting the headwaters of the Colorado River across state lines and public and private ownership. He was fired up to contribute to the negotiations over the management of the Colorado that are now underway. We could have used Pat’s perspective and leadership on these and other issues.

Fortunately, family members and other colleagues have already publicly committed to continuing Pat’s work. We will need the best the West can offer to fill his shoes.