Roots and Rivers: The crucial connection between forests and watersheds

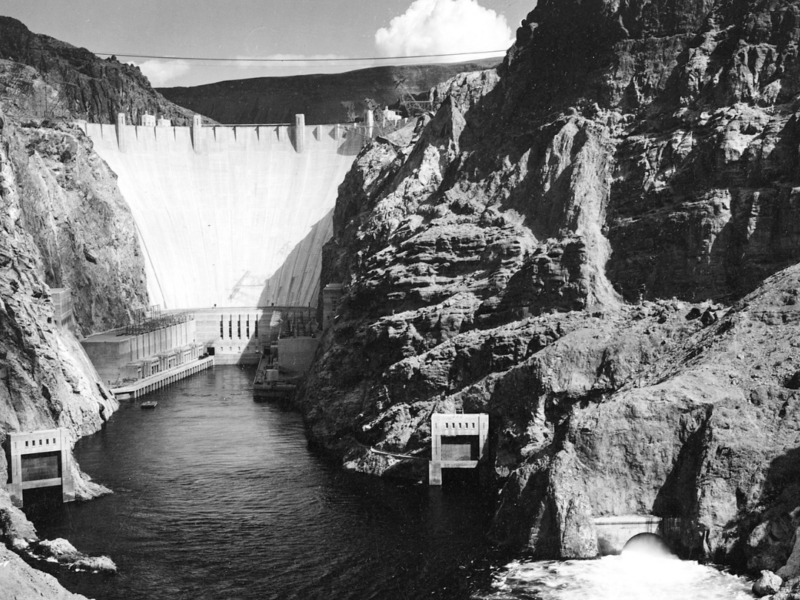

As of July 30th, 89 large active wildfires had burned 2,123,318 acres and counting in the United States. Nearly 5 million acres total have burned already this year. Those millions of acres contain vital wildlife habitat, grazing and farm land, and, crucially, water sources for millions of Americans.

In the third of our Summer Water Webinars, we convened a panel of watershed collaborative members and organizers to learn about how collaboratives leverage their collective voices to accomplish projects that benefit forest and watershed health across the West. Meghan O’Toole Lally with the Ladder Ranch and member of the Headwaters of the Colorado Initiative; Ken Brenner long time community organizer and public official, and member of the Headwaters of the Colorado Initiative; Lily Bruce of the 2-3-2 Partnership and Forest Stewards Guild, and Cindy Super with the Blackfoot Challenge joined WLA on July 26th to discuss how collaborative relationships with diverse stakeholders can create the opportunity and capacity for large scale forest and watershed health initiatives.

The Headwaters of the Colorado Initiative

The webinar began with an examination of the motivation behind forming the Headwaters of the Colorado Initiative (HOC) which aims to create a resilient and functioning forested headwaters within the landscapes of the Little Snake and Yampa Rivers of Wyoming and Colorado through science-based ecosystem planning, coordinated partnerships, focused funding, and collaboration across all lands. The HOC was born of the need to balance production and conservation, improving the health of the landscape while producing food and fiber. The O’Toole family, seeking to improve irrigation water delivery systems, began working with the Fish and Wildlife Service to create fish-friendly diversions that were healthier for the rivers and streams. .

This effort inspired Pat O’Toole to begin organizing the Headwater of the Colorado Initiative to expand the efforts he’d made on the watershed that feeds his family’s Ladder Ranch to the landscape scale. The HOC now covers 1.9 million acres and is focused on improving forest health and increasing water yield. Unhealthy forests, O’Toole Lally said, tend to increase melt and runoff rates, while healthy forests can retain water for longer periods and slow runoff. The HOC is focused on improving forest health through controlled burns, mastication of timber and brush, water impoundments, irrigation structures and efficiency, and stream restoration after a large-scale die-off of lodgepole pines in the region almost twenty years ago and decades of unintentional mismanagement.

O’Toole Lally quoted her father, saying, “You can’t solve a million-acre problem with a hundred-acre solution.”

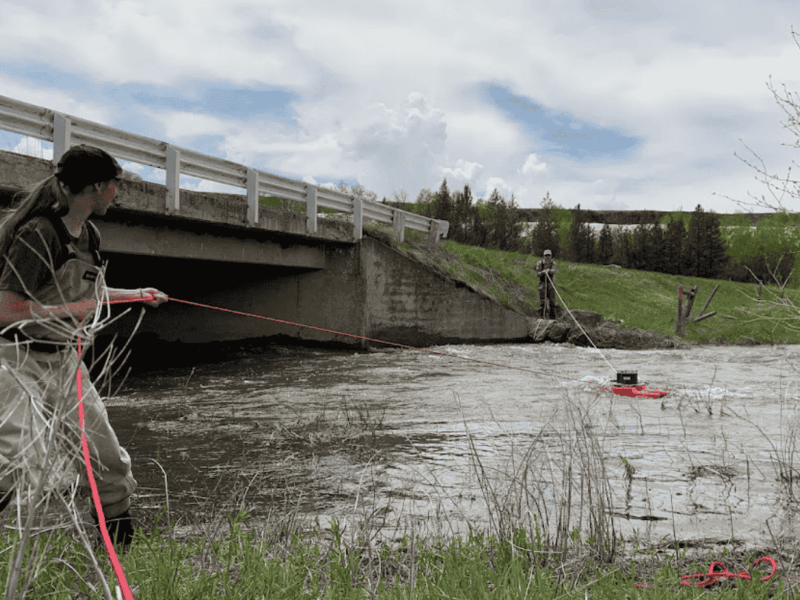

Ken Brenner spoke to the importance of bringing diverse stakeholders to the table, and how to balance agricultural needs with forest health, highlighting the important work that has been done to improve infrastructure on the Little Snake River. Brenner focused on the importance of listening and establishing common goals through a transparent process. With a diversity of partners, applications for funding are more likely to be successful and those partners must include local, state, federal and quasi-governmental agencies (conservation districts), NGOs, private landowners and the public at large and begin with an inventory of current efforts to identify gaps and capacity issues in getting projects done on the ground.

The 2-3-2 Partnership

Lily Bruce of the 2-3-2 Partnership spoke next, reflecting that Brenner’s point about humility really resonated with her experience. The 2-3-2 Partnership, which stands for two watersheds, three rivers, and two states, works in an area of over 5 million acres that provides drinking water to Santa Fe, Albuquerque, the Jicarilla Apache Nation, and many more communities downstream. Prior to the formation of the 2-3-2, the landscape had seen a dramatic increase in severe wildfires and partners in the area recognized a need to reduce the risk of uncharacteristic wildfire, increase fire-adapted communities, and improve water quality and watershed function.

The 2-3-2 is focused on coordinating many smaller, community-based collaborative groups to streamline project planning and access more funding. They are currently implementing the Rio Chama Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP) which prioritizes projects on federal lands. The partners have leveraged the CFLRP to access additional funding for the area. Lily underscored the importance of remembering that “success,” when it comes to natural resource management, does not look like a single project that “fixes” a landscape, but instead the ability to perpetually, proactively and collaboratively manage those resources as the landscape evolves and conditions change. Efforts must also look to the connectivity of landscapes and watersheds, and include all landowners and managers, private and public.

The Blackfoot Challenge

Finally, we heard from Cindy Super of the Blackfoot Challenge. The Blackfoot Challenge works together, across boundaries and landownerships to conserve natural resources and a rural way of life, including working ranches, logging and fire work. It was started by private landowners and covers 1.5 million acres around the Blackfoot River. The area supports recreation, logging, multi-generation ranches, and sheep herding. It also has robust grizzly bear and wolf populations. The Blackfoot Challenge is working to protect these landscapes and the people and wildlife they support through a collaborative project process. With a 30-member board that must agree on new projects by consensus, the Blackfoot Challenge has managed to retain a lot of community support for projects. To smooth collaboration, they rely on the “80:20 rule”, or the understanding that not everyone is going to agree on everything: focusing on the 80% that they do agree on allows them to stay focused on working together.

Super shared that they began their forestry program in 2007 and their prescribed fire program in 2017. It wasn’t exactly easy to convince 30 people that they should begin to intentionally light parts of the landscape on fire, Super relayed. The forestry program seeks to correct earlier land management practices, such as fire suppression and excessive logging, that are having long term deleterious effects on landscape health. They work with private landowners who want to “cut their trees and light their land on fire” to help mitigate those impacts, Super said. They are also part of the fire learning network, and statewide prescribed fire council. The forestry program works hard to understand and incorporate the latest science, and adjusting to new understandings of how forests are healthiest.

Major takeaways

All of the presenters underscored the connection between healthy forests and healthy rivers. Each of the regions served by these collaboratives have overstocked forests that evolved with fire but have not seen fires in a century due to intentional suppression. Increased fuel loads in these areas increases the risk of catastrophic wildfires that contribute to decreased water quality and flooding. Proactively managing these forests and watersheds across management boundaries is the only way to address these issues at the scale necessary. As collaboratives work on projects at the landscape scale, there is a lot we can all learn and share with each other west wide.

The next water webinar in the series, “Reviving through Regreening: Exploring opportunities for reversing desertification” takes place August 30th. Register Now.