Decades of experience with this conservation challenge has left longtime Private land wildlife manager Rick Danvir with some wisdom, and some scars.

When I signed on with Deseret Ranch back in the early 1980s, we were struggling to make payroll. The cost of raising beef – the growing and feeding of hay, the maintenance of irrigation and grazing infrastructure – was outpacing revenue. Bill Hopkin, the just-hired cattle manager summed it up this way: “We were budgeted to lose a half million dollars and achieved our goal!” Clearly, we needed a new plan, one to keep the ranch physically and financially intact.

Through strategic changes in the management and use of irrigated lands, along with changes in livestock management, the cattle enterprise became profitable. Equally important was the development of a cost-effective plan to manage the big game resources on the ranch, particularly the 1,500+ head of elk that depended on the ranch for year-round forage and habitat.

By managing hunter numbers and harvest quality, we developed a profitable hunting program – leading to better management of wildlife, sportsmen and livestock. Big game forage and habitat needs became part of the strategic planning process. We learned the hard way that if we didn’t plan for the needs of wildlife, they might not be there come hunting season. Worse yet, they might impact an unlucky neighbor.

Private Lands – Public Wildlife issues

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation

The model was developed in the early 20th century in response to rampant overhunting and wanton industrial waste and misuse of wildlife resources, notably the near extermination of the bison, pronghorn, elk and beaver. It is generally agreed that it consists of seven principles, yet, as the Wildlife Society wrote in its 100-year Technical Review of the model in 2012, “Indeed, the Model itself is not a monolith carved in stone.”

- Public Trust Doctrine – An 1842 U.S. Supreme Court opinion, in Martin v. Waddell, established the legal precedent that it was the government’s responsibility to hold wild nature in trust for all citizens.

- Democratic Rule of Law – Wildlife is allocated for use by citizens through laws, and all citizens can participate in developing systems of wildlife conservation and use.

- Opportunity for All – Every citizen has the freedom to hunt and fish, and public access to their wildlife resources is a right of citizenship.

- Prohibition on the Trade in Dead Wildlife – To uphold the first principle in service of the second and third, it was necessary to establish that public ownership of wildlife was for personal use, including to feed one’s family, and not for profit-making, which was leading to the destruction of wildlife species in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Nonfrivolous Use – In North America, we can legally kill certain wildlife for legitimate purposes under strict guidelines for food and fur, in self-defense or for property protection. Laws are in place to restrict casual killing, killing for commercial purposes, wasting of game and mistreating wildlife.

- International Resources – Because wildlife and fish freely migrate across boundaries between states, provinces and countries, they are considered an international resource, which means that their management should also be governed by international treaties and laws.

- Scientific Management – The best science available will be used as the basis for informed decision-making in wildlife management.

Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to help manage wildlife on private lands throughout the West. The management challenges and solutions don’t vary all that much. However, the attitudes, policies and programs governing the management of public wildlife on private lands vary significantly among the Western states. In addition to traditional outfitting and other leases, some states provide guaranteed, landowner-assigned permits in exchange for regulated public access and habitat conservation. Other states reject programs their hunters perceive as privatizing wildlife management and creating inequalities in permit allocations.

The degree to which landowners are enabled to participate in state wildlife management depends on how the “Equal Opportunity for All” tenet of the North American Model of Wildlife Management is interpreted. Different definitions of equal opportunity have led to differing policies. The sporting public’s aversion to landowners charging access fees and monetizing hunting and fishing recreation on their properties seems largely a concern with fairness: that all citizens should have equal opportunity to obtain permits and hunt for an affordable price. Some state wildlife agencies are concerned that if hunting is only available for a fee, then the public in general will not participate and will not grow up experiencing their commonly stewarded wildlife. If they don’t participate, the logic goes, they won’t care about wildlife and wildlife conservation, nor understand the role of hunting in wildlife management, resulting in decreased acceptance of hunting and less funding for wildlife conservation. This concern is not without merit.

However, my concern goes beyond keeping the public interested in the great outdoors. To successfully conserve wildlife into the future, we must simultaneously maintain wildlife-based recreational opportunities for the public while also adopting programs that equitably distribute the cost of stewarding wildlife across a broader public, not just that portion of the public who own wild or working wild landscapes.

Policies regarding private lands-public wildlife management influence a landowner’s ability to manage habitat, depredating wildlife or the sporting public. This should be a concern to anyone who cares about the welfare of Western wildlife, since the ability and willingness of landowners to provide wildlife habitat impacts the abundance and distribution of our wildlife resources throughout the West.

To be clear, the landowners I’m talking about are those who own and manage the privately owned acres of forests, rangelands and wetland habitats not yet developed into housing projects. Many of us own land, but most of us don’t own land suitable for habitation by elk, wolves, sage grouse or prairie chickens. Much as we may cherish these species, they no longer exist in most of our backyards.

Another tenet of the North American Model is that the stewardship of our wildlife resources is the responsibility of all citizens, not just those who own undeveloped working lands. Along with the opportunity for all citizens to enjoy these resources comes the moral and fiscal responsibility to manage them. Unfortunately, those who own and operate working lands bear a greater fiscal and management cost than the rest of us. The reality is, we all need to support working landowners: They can’t do it alone.

Private lands provide essential habitat and water for many wildlife species. In fact, with the severe drought affecting the West, many of the wildlife and feral horses on our public lands depend on water, wells and pipelines developed and maintained by the ranching permittees leasing those lands.

Landowners manage working lands to meet their financial, land health and family or community goals. After all, agricultural operations are businesses, and managing access to and activities on the land is key to effective management. The management, security and solitude of private lands also offers many wildlife species a preferred environment in which to meet their habitat needs. Unfortunately, this explanation provides little comfort to those of us seeking wild places to hunt, fish, enjoy nature, recharge ourselves and fill our freezers – after all, the wildlife belong to all of us, not just those fortunate enough to own a ranch.

So, what’s the solution? Unrestricted access to private lands would make ranching, an already challenging job, even tougher. It would also be tougher for wildlife seeking quiet places to reproduce, raise their young or survive the winter. If done poorly, increasing access reduces habitat quality, wildlife survival and abundance. Too many people also affects the quality of the recreational experience. Long-term sustainable solutions must balance the needs of landowners, recreationists and – most importantly – wildlife.

Private lands provide essential habitat and water for many wildlife species. In fact, with the severe drought affecting the West, many of the wildlife and feral horses on our public lands depend on water, wells and pipelines developed and maintained by the ranching permittees leasing those lands.

Private lands wildlife programs

Many different policies and programs have been developed in the Western states and provinces to help solve this problem. These programs differ significantly, depending on the culture and attitudes within each state regarding the private lands-public wildlife (PL-PW) issue. Some states have proactively developed programs that encourage landowners to profitably manage big game populations in exchange for providing wildlife habitat and/or public hunting opportunities.

Effective PL-PW programs not only improve access to private lands, but also increase wildlife abundance and recreational opportunities on public lands within the region. At Deseret Ranch, using the Utah Cooperative Wildlife Management Unit program (CWMU), we stabilized the elk herd numbers by providing free, guided hunts to 200+ antlerless hunters, and provided a quality experience to 50+ guided bull hunters annually. Through a state drawing, public hunters received all the ranch antlerless permits and nearly 20% of the ranch bull hunts each year. The remaining bull permits were directed to paying hunters. Monitoring data revealed that about 60% of bull elk born on the ranch left (emigrated) as young bulls. These bulls were harvested off-ranch on public land in at least four states (Utah, Wyoming, Idaho and Colorado).

Effective PL-PW programs not only improve access to private lands, but also increase wildlife abundance and recreational opportunities on public lands within the region.

So, most of the bull elk hunters on the ranch were fee-paying hunters. However, of the 250+ elk harvested on the ranch each year, nearly 80% were harvested for free by public hunters. In addition, for every bull harvested on the ranch, two others left the ranch. We maintained a large, healthy elk herd, provided top-notch hunting opportunities (on- and off-ranch), we paid our bills and remained a working ranch. I’d say that’s a win for wildlife, sportsmen and women, and the ranching community.

Fee-hunting programs are not the only effective private lands-public wildlife programs. Years ago, I was part of a conservation-minded partnership that purchased a ranch in the North Dakota badlands. The ranch provided excellent grazing and habitat for both game and nongame wildlife species. Grazing revenue alone, however, wouldn’t cover the land payments. Rather than developing a fee hunting program, we enrolled in the North Dakota Working Lands Program (PLOTS), which provides cost-share and access payments for management practices, habitat improvements and public walk-in access. Again, working lands were conserved, sportsmen and women gained private land hunting opportunities, and the land payments got made!

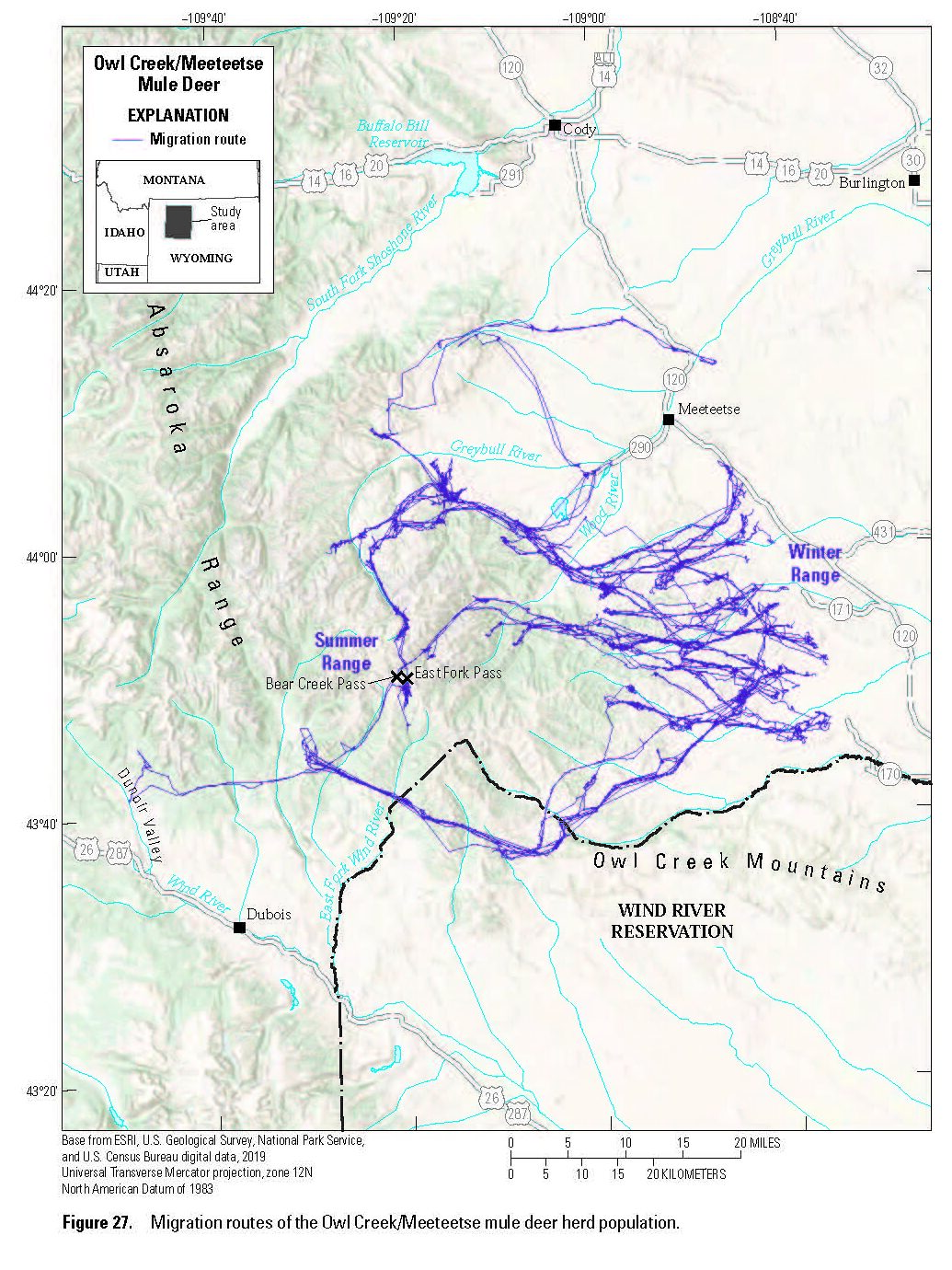

The Owl Creek/Meeteetse Mule Deer migration map at right shows a clear example of big game seasonal movement across boundaries and topographies, from summer range in public land to winter range in mostly private farm and ranchland in the lower country. Courtesy of USGS.

Wildlife don’t read maps

So why the concern about keeping private ranches as working lands? Why not just focus our wildlife management efforts on public lands? Because topography and water distribution affect land ownership, migrations, wildlife diversity and abundance. While most of the Great Plains is privately owned, land ownership in much of the West includes privately owned valleys and foothills, interspersed with publicly owned mountains and basins. These lands are more suitable for agriculture, homes and cities than are the snowy, forested mountains or the hot, dry basins. However, these same lands provide irreplaceable habitat and movement corridors for migratory wildlife.

Fee-hunting programs like the Utah CWMU, Colorado Ranching for Wildlife (RFW), New Mexico EPLUS and California Private Lands Management program (PLM) all provide financial assistance to landowners managing wildlife habitat by issuing landowner-directed permits to designated hunters. This works well for landowners hosting big game in the hunting season. Unfortunately, in mountainous areas where summer and winter ranges are spatially separated, the benefits of fee-hunting programs may not be shared by privately owned lands where big game winter. These lands often host antlerless, herd management hunts but not antlered hunts for migratory big game. So, while big game hunting revenue is helping support the “upstream” landowners, their “downstream” neighbors may winter the herds at their own expense. This “have and have not” scenario can cause problems.

Since big game winter habitat is essential to herd survival, the needs of downstream landowners must also be addressed. Some programs might be expanded to include adjacent, privately owned winter-spring habitat. The Utah mitigation permit program was specifically developed to provide landowner-assigned antlerless permits to downstream landowners to help mitigate forage losses and manage wintering elk. Enrolled landowners gain greater management control of elk hunters, elk distribution and abundance on their land. Landowners can assign their permits to competent, trusted hunters or even hire outfitters to manage the hunt. While not financially based, state-sponsored hunter training and coordination programs are helping to improve hunter ethics and effectiveness. Hopefully, these programs, in combination with walk-in access and extended antlerless seasons, will improve population management and improve landowner tolerance of hunters and big game wintering on private agricultural lands.

In the vast basin and range topography along the Rockies, long big game migrations between summer and winter habitats are common. To thrive, big game need long, barrier-free movement corridors stocked with nutritious groceries (“stopover habitats”) in which to forage along the way. Migration corridors routinely cross multiple, intermixed federal, state and privately owned lands. Migratory big game follow newly greening forage upslope each spring, spending most of their time feeding and regaining body condition in stopover areas.

Perhaps the most complicated and contentious PL-PW issues occur on the intermixed public and private lands surrounding Yellowstone National Park, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. In addition to conflicts over big game forage use and crop depredation are the added issues of disease (brucellosis) and wolves. Programs designed to maintain wildlife habitat, reduce conflict, and provide hunting opportunity in this vast area may need to be addressed at the watershed or herd management-unit scale rather than the ranch scale.

In the vast basin and range topography along the Rockies, long big game migrations between summer and winter habitats are common. To thrive, big game need long, barrier-free movement corridors stocked with nutritious groceries (“stopover habitats”) in which to forage along the way.

Programs do exist to target financial and technical assistance for private land management revenue based on the amount and importance of privately owned acres of big game habitat within a big game management unit. The Utah Limited Entry Landowner Association and Colorado Habitat Partnership (HPP) are both programs designed to be implemented at the management-unit scale. These programs provide a percentage of either hunting permits (UT) or license-sales revenue within the management unit (HPP) to landowner associations or local collaboratives for conflict mitigation and management within the herd unit. Basically, a portion of revenue derived from hunting (based on private acres or total permit sales within the unit), helps mitigate for big game conflict.

While some prefer the “user pays” approach of using hunting revenue to finance wildlife conservation on private lands, this is not the only funding opportunity. Again, using the Yellowstone National Park example, why not pass a portion of the wintering wildlife costs to the millions of tourists visiting the park to view and enjoy wildlife? The elk populations enjoyed in Yellowstone Park during the summer months are dependent on both private as well as publicly owned fall-winter-spring habitats for their survival. Some herds spend as much as 80% of the winter on private land. A few dollars per carload could improve management throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Thinking even more broadly, perhaps a habitat leasing program compensating private landowners providing essential habitat, funded by all Americans at the federal level, might be the most equitable approach of all.

We have to pay somehow

Many sportsmen and women still decry the use of landowner preference permits or any type of programs aimed at rewarding or assisting landowners for managing habitat. However, is it really all that different to direct a portion of big game permits to pay for habitat on private lands than directing permits to pay for habitat through conservation organizations? If allowing landowners to derive some wildlife revenue results in better conservation and management of our wildlife resources, then PL-PW programs and permits benefit not just landowners but also sportsmen and wildlife.

A few dollars per carload could improve management throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Thinking even more broadly, perhaps a habitat leasing program compensating private landowners providing essential habitat, funded by all Americans at the federal level, might be the most equitable approach of all.

If we conclude that the perceived loss of opportunity by sportsmen due to private lands hunting programs are intolerable, we need another program to help landowners cover the cost of providing for the wildlife displaced from our developed residential and urban landscapes. Last I checked, there are several hundred million structures on the landscape in the West. At 10 bucks a roof we might solve myriad wildlife management issues on both private and public working lands, don’t you think?

Rick Danvir is a wildlife biologist, former wildlife manager for Deseret Western Ranches and founder of Basin Wildlife Consulting.