Wyoming’s Sublette County

Unimaginable Change

Domestic sheep flocks have grazed these private pastures in the southern end of the Wind River Mountains for more than 100 years. It was about 15 years after wolves were released several hundred miles to the north in Yellowstone National Park that they became problematic in our area.

Things were different then: wolves were still under the strict federal protections of the Endangered Species Act, and they were both highly visible and highly visited by Yellowstone tourists. Those wolves had no reason to fear humankind and didn’t suffer negative consequences from their human encounters. It was only a matter of time before nine members of a national-park based wolf pack dispersed from their natal pack as two-year-olds and journeyed south. Killing cattle here and there as they traveled along a river corridor, the wolves eventually strolled down a county road on their way to our sheep flock.

Fortunately, we’d been warned shortly before dark that there were wolves in the neighborhood and had night-penned the flock next to the house. The wolves hit the pen after dark, and when the sheep broke down the gate to escape, we were there to help them, chasing the wolves out of our yard and around our corrals with a pickup truck. Two of the wolves were killed by federal officials the next morning because of their repeated livestock depredations and bold behavior, but others continued their forays elsewhere.

We spend a lot of time, effort, and money trying to protect our animals…. The result is that our ranch decision-making is primarily about managing for wolves – not livestock or pasture health – in an area where wolves may be killed at any time.

Cat Urbigkit

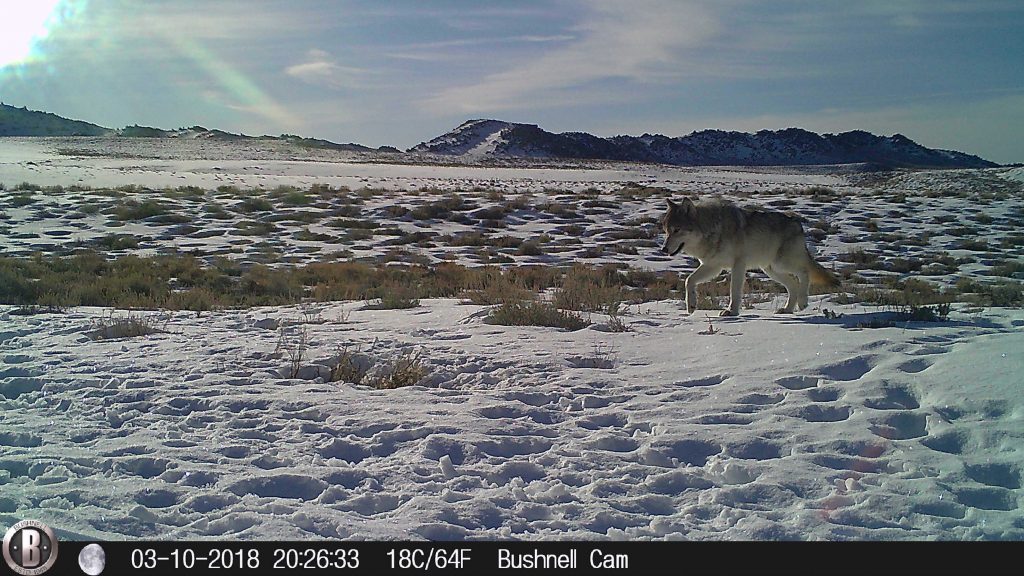

Contemporary wolf behavior in Wyoming bears little resemblance to that of those early, fully protected wolves. When the Wyoming Game & Fish Department (WG&F) took over management of the recovered wolf population in 2017, it instituted a regulated wolf hunting season in northwest Wyoming’s trophy game area, while wolves in the remainder of the state were classified as predators in that they may be taken at any time, for any reason, without restriction. We run sheep and cattle about 10 miles outside the trophy zone, but wolves within that zone serve as our seed population. Since wolves are classified as predators in our area, they receive a lot of hunting pressure and the wolves that survive here are intelligent, elusive, and nocturnal.

WG&F is responsible for both the management of wolves within the trophy zone, and in compensating producers for livestock depredations by wolves in that area. In contrast, there is no agency responsible for managing wolves in the predator zone, and there is no compensation for losses. Thus, county-level predator boards work with USDA Wildlife Services to control problem wolves in the predator zone. We’ve learned that it takes these highly skilled animal-damage-control specialists to find and eliminate wolves that repeatedly prey on livestock. Hunters, ranchers, and the general public may kill wolves, but unless the problem animal is targeted for elimination, livestock losses will continue.

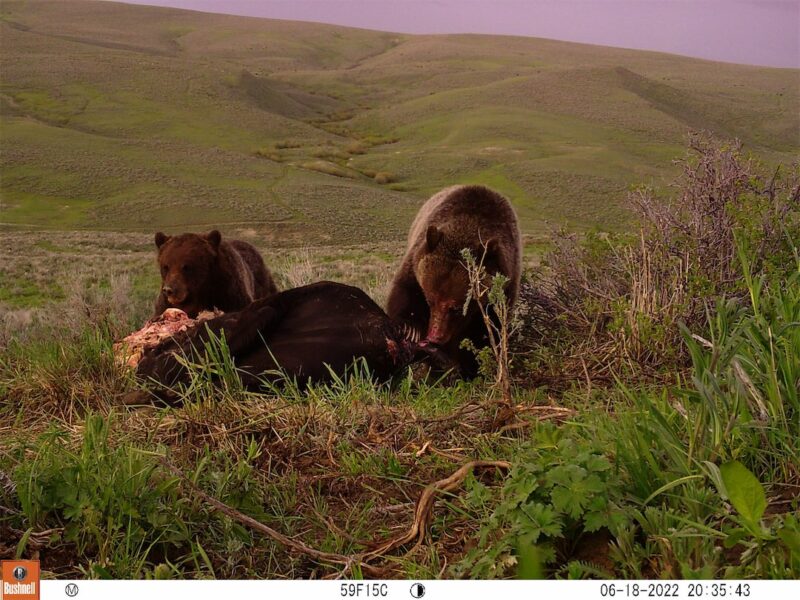

We spend a lot of time, effort, and money trying to protect our animals. The list of non-lethal techniques we use on the ranch now tallies 17 – everything from running livestock guardian dogs with both cattle and sheep, to night penning the sheep, and changing livestock herd compositions and pasture rotations based on wolf activity rather than range condition. We have implemented an intensive program to monitor wolves on the ranch, including installing game cameras, conducting routine track surveys, and working with Wildlife Services in trapping and radio-collaring wolves. This allows us to know more about individual animals that are using the ranch at any given time. Neighboring ranchers are doing the same, increasing our knowledge of wolves on our range. The result is that our ranch decision-making is primarily about managing for wolves – not livestock or pasture health – in an area where wolves may be killed at any time.

The basic dynamics of the predator-prey relationship dictate that at some point, all non-lethal methods will fail, and that’s when we turn to lethal control. Our lethal wolf control efforts are always conducted to stop immediate, repeated depredation events, and are never an attempt to eliminate the wolf population.

A few years ago, for example, our beloved livestock guardian dogs fought a resident wolf pack for the rangeland around our ranch headquarters, with numerous dogs injured or lost to the wolves in a conflict that raged for months. It was sickening, and heartbreaking, and continued until that particular wolf pack was eliminated through lethal control. As was expected with a robust wolf population, it was only a matter of time before other wolves moved in to take that pack’s place, and although there are occasional skirmishes, these other packs haven’t developed the problematic behavior of attempting to eliminate our guardian dog pack.

When a wolf pack attacks our sheep flock, it’s an absolute emergency scenario. I pray for cell service at that spot, because I’ll need to place three immediate calls: the first “all-hands-on-deck” call to my family for immediate help at that location; the second to the nearest wildlife official to confirm the kills; and another call for animal damage control assistance. At the same time, I’m counting dead animals, finding walking wounded, putting down wounded animals that can’t get up, preserving the evidence from scavengers, getting nervous sheep gathered and inventoried, locating and checking the conditions of each guardian dog, jotting down the locations of other wounded animals that will need to be retrieved and hauled to safety, and providing immediate veterinary care – all while racking my brain trying to figure out the safest location we can move the flock to before dark, knowing that the wolves will return.

Even after the immediate emergency is over, the aftermath poses other difficulties. When a wolf pack hits a sheep flock, every component of that flock goes into a heightened state of anxiety, including individual sheep, the guardian dogs, and we human herders. It’s difficult to manage unsettled animals, with those difficulties including sheep that don’t want to go into (or stay) in areas where the flock has been attacked, guardian dogs that get testy and on the fight, and sheep that will flee from the same working herding dogs they’ve known all their lives. We humans are sleep-deprived and alternate through grief, anger, and numbness.

The economic impact of the direct death loss is usually minor compared to other costs such as the wounded and missing animals, stress-related loss of condition, decreased productivity, and increased labor. The emotional toll is even higher, and all these costs are incurred as we are actively trying to stop the current conflict.

We’ve learned that while a lot of people have idealized views of what it’s like to live with wolves, that rarely aligns with reality. And we know that what works for us may not work for our neighbors – just as every family is different, every ranch is different. There will never be a perfect system of protecting livestock that is both economically feasible and capable of being handled in all field conditions. We are always trying to minimize conflicts, but where wolf populations occur in robust numbers, the livestock industry diminishes in some way. Along with the emotional and financial toll, our family has effectively ceded a portion of our historic grazing range to wolves. Others have been forced by the rising costs of managing with wolves to give up their federal land allotments.

One may wonder why we spend so much effort managing for wolves, suspecting a desire for coexistence motivates us. But that would be incorrect. We haven’t given wolves space on the landscape – the wolves have taken it. We play the hand we are dealt, while knowing that our ranch’s survival is dependent upon the health of the shared landscape in which we live.

Cat Urbigkit is a shepherdess, former newspaper reporter, and author of fiction and non-fiction books for children and adults, including Return of the Grizzly.