Catron and Apache Counties, New Mexico and Arizona

As a rancher with livestock in the Mexican Wolf Reintroduction Area (MWRA), I am constantly bombarded with media narratives and Facebook posts extolling the virtue and necessity of wolves prowling across every piece of open country in North America. Even if after years of ranching with them it remains difficult for me to ascertain their virtue or how necessary they are, I still believe wolves, like bears and lions, are part of the working wild that I call home.

So it was that eleven years ago when we first started to deal with wolves on our ranches north of the Gila Wilderness in New Mexico and Arizona, I listened to the various wolf advocacy organizations and read everything I could find online and in print about how to deter wolves from killing our livestock. Since we operate on a large area (over 280,000 acres in wolf-occupied country) with year round public land permits and no irrigated pastures for calving, our only practical deterrence option appeared to be range riding. We hired range riders and got after it. We didn’t have many wolf packs on our ranches in those days and we usually lost only very few if any calves.

But we didn’t know whether we were preventing wolf attacks or were just “recreational” range riding. That’s the thing about the scientific method of gaining knowledge. To be really scientific you need a control group, and the experiment should be repeatable. Like one of my smart friends once said, “science is good for studying dead things.”

Nowadays, most of the world’s humans are disconnected from the everyday ebb and flow of nature and they are uncomfortable seeing or hearing of death.

Nelson Shirley

Over the years, as the wolf population grew, depredations became more frequent and sometimes we had multiple depredations in a single night. We quickly learned that to be effective deterring wolves we had to be out there all night. But range riders are not machines and need rest, so night patrols meant hiring more range riders, all at huge cost. Still we experienced greater livestock losses each year. During one of the worst bouts of cow/calf killing, Wildlife Services trapped a wolf, and suddenly, like flicking a switch, our depredations stopped cold for nine months in that area. The removal of a problem wolf (lethally, or to captivity) has proven repeatedly to be a sure way to stop or dramatically reduce depredations. (We’ve subsequently also learned that even catching a wolf in a trap that’s intended for coyotes will scare wolves out of an area for an extended period of time. So the use of leghold traps for coyotes has been an important, if controversial, non-lethal method of wolf deterrence.)

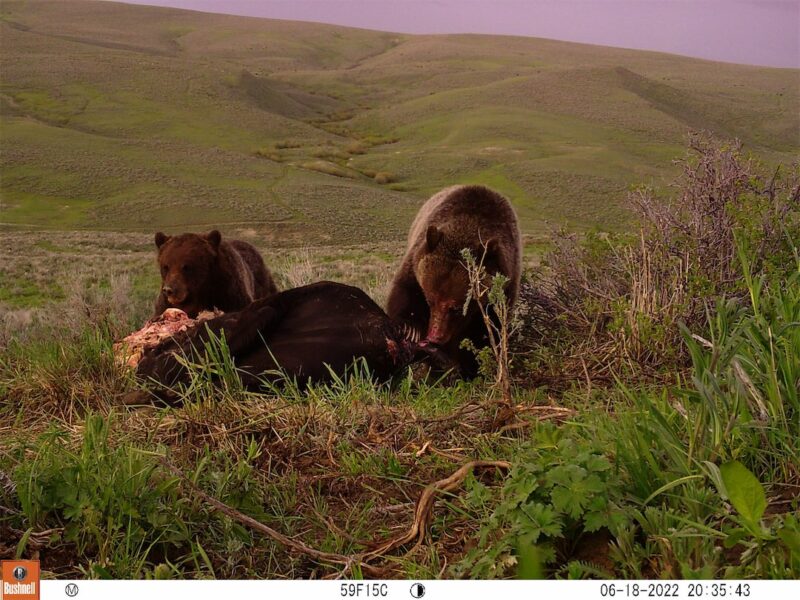

Nowadays, most of the world’s humans are disconnected from the everyday ebb and flow of nature and they are uncomfortable seeing or hearing of death. Modern cosmopolitan society has gone to great lengths to cordon itself from death. But death remains a part of life. This difference, between those that experience death on a regular basis and those that don’t, separates rural and urban people more than any other.

This cultural difference really comes home to roost when it comes to the issue of wolves. Wolves have co-existed with elk, deer and moose for thousands of years, by killing them. Our ranch is also co-existing with wolves as pastoralists the world over have for millennia, and that means we kill wolves (through Wildlife Services, since wolves are protected by the Endangered Species Act here) when they start killing our livestock. Like us, when predators leave their herds alone, pastoralists don’t spend time and energy hunting them. Today we have at least seven wolf packs on our ranches. Our losses to wolves in 2019 were over 120 head out of about 2000 mother cows/calves, 33 of which were confirmed. This annual loss rate of about 5.5-6.0% mirrors the Mexican Wolf Recovery Area loss rate in general.

When ranchers describe the economic reality of wolf depredations a common response is that public lands ranchers are subsidized “welfare bums” due to low grazing lease fees. Livestock grazing is supposedly an insignificant source of revenue from public lands, so it is no big deal to eliminate it, and ranching in the American west is just not that important economically. So, the argument goes, if livestock grazing is in conflict with wolves, just eliminate public grazing, and let ranchers get real jobs.

Whether you like beef or not, western ranch operations preserve open space and provide some of the best habitat in the western US. Without working ranches, the unintended consequences would often be subdivision and ranchette developments.

Nelson Shirley

Let us take these arguments one by one. Is ranching as a use of public lands subsidized? To determine, a comparison with private grazing leases is required. The average cost for a private lease in the southwest is about $12 per annual unit month, or AUM, a standardized grazing unit calculated for each allotment, compared to $1.69 per AUM for a federal lease. However, ranchers leasing private land do not have to buy the lease upfront as they do for public land leases (which adds significant amortized capital cost), the cost of fencing and water development on private land are paid by the lessor, and the public does not have any access to the leased private land. For a 300-head year round cow/calf operation, for instance, these differences result in comparable costs of about $42,000/year. This does not take into account that private leases are also usually on more productive country.

The cost to Federal agencies to manage grazing on public lands is also frequently called out as a reason to curtail or eliminate public lands grazing use. In 2018 the USFS, for example, “lost” $48 million managing grazing on national forests ($57 million spent less $9 million paid for permits), which sounds like a big subsidy. But note that in the same year, USFS “lost” over $232 million managing recreation, wilderness, fish, and wildlife ($402 million spent less user receipts of about $170 million dollars), which could lead to the uncharitable view that all the hunters, anglers, kayakers, OHVers and backpackers traipsing across our public lands are the real “welfare bums.” If we evaluate the investments our public lands agencies make in these resources solely by the resource’s ability to generate revenue for agencies, guess what the only permitted activities on those lands would be: mining and fossil fuel extraction.

To the question of whether or not public lands are important to ranching and livestock production in the west, USDA statistics show that the eleven western states raised 6.1 million of the total national herd of 30 million head in 2016 (the last year complete data is available). That year, total authorized livestock on BLM and USFS rangelands totaled 2.4 million head. In other words 40% of the beef cattle in the 11 western states spend part or all of the year on public lands. In practice, this means that without the public lands, most private ranches would not be viable operations. In 2018, cow/calf production made up 2.9% of Montana’s GDP and 2% of New Mexico’s. For comparison, outdoor recreation’s share of Montana’s GDP was 2.2%, the largest contribution of that sector to the economy of any state. Further, crops that make up the biggest share of agricultural production in other states include oranges at just about .1% of Florida’s GDP, wheat in Kansas at just 1% of state GDP, and corn at 4.4% of Iowa’s GDP. How many large carnivores, let alone other species, do wheat and corn fields typically accommodate?

Meanwhile, despite an overall reduction of nearly 50% in livestock numbers on western public rangelands since the mid 1950’s, biodiversity continues to decline. The culprit in most places is not grazing, (or even logging or mining) but the damage and fragmentation of habitat caused by increasing public access for recreation and, more critically, the associated development of vacation homes and subdivisions in the critical wildlife habitat of valley bottoms and along rivers and lakesides. Any place that has water and is attractive to humans is important to wildlife.

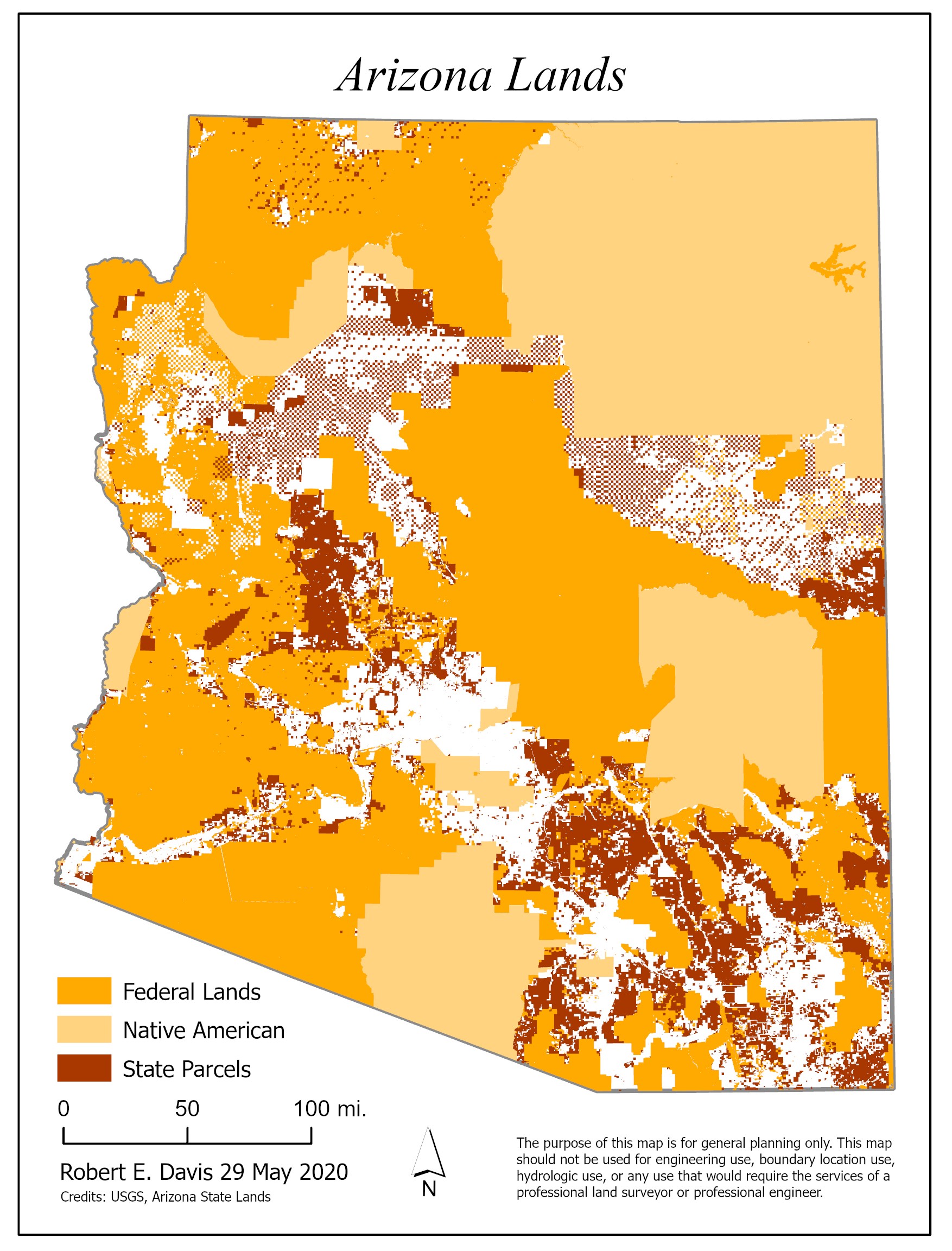

This threat to open space is hardly theoretical. In Arizona, only 17% of the state land mass is in private ownership: the rest is tribal, federal or state land. This private land includes Arizona’s few precious open valley bottoms along our even fewer year-round rivers: landscapes that were refugia for wildlife for millennia. Of that 17%, fully half has already been subdivided and developed. Whether you like beef or not, western ranch operations preserve open space and provide some of the best habitat in the western US. Without working ranches, the unintended consequences would often be subdivision and ranchette developments.

Ranchers who actually care for livestock generally don’t like wolves for a good reason. Anyone who has real hands on experience with wolves knows that wolves typically kill large prey by consumption—that is, they begin eating their prey alive. The process is neither quick nor pretty. Ranchers have the same human, emotional response as anyone would to the pain and suffering their livestock and working animals experience, due to wolves inability to deliver lethal bites to large prey. It’s not the fault of wolves, but it is the basis for a very human, and humane, distaste for wolves in agricultural communities. Today, the vast majority of Americans will never experience firsthand the depredations of wolves: and conservation ranchers who don’t raise livestock or can afford the losses have little to lose by the presence of wolves.

As ranchers in the working wild, we still believe wolves have a place here. Wolves are neither saints nor sinners: they won’t make rivers run again and they probably won’t eat you, but they definitely will increase the cost of operating a ranch, and that cost has up to now been borne primarily by the rancher. If you’re considering wolf reintroduction, demand to know the true costs, and who will be asked to bear them. Or you might find that a move you thought was pro-biodiversity has led instead only to more pavement and power lines.

Nelson Shirley is the president of Spur Lake Cattle Company, a combination of six ranches in Catron and Apache counties of New Mexico and Arizona.