Species Conservation Banking and Habitat Exchanges

Conservation Finance Series—Part Three of Eight

How does species conservation banking work?

The Federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), as well as some other federal and state regulations, prevents the destruction and harassment of protected species. This protection extends also to the habitat these species use throughout their life, such as habitat for nesting, rearing young, foraging, and migrating. A landowner who seeks to modify a parcel that contains protected species habitat will often be required to obtain a permit from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and other regulatory agencies. In contrast to wetland and stream mitigation, where the impact is typically limited to the exact footprint of the ground disturbance, impacts to protected species can potentially extend well beyond the location of the actual project. For example, a mining project can generate noise and dust that pushes wildlife miles away from the site. Certain species, like the Greater Sage-grouse and mule deer – though neither are listed species – are particularly sensitive to this type of land disturbance.

Federal agencies recognize that it is not always possible to avoid impacts to species and their habitat; however, impacts are required to be offset such that the overall quality and quantity of species populations is maintained. In most of the country, with the notable exception of California, offsets have been mainly provided in-kind by project proponents through the purchase of conservation easements on properties with a matching habitat. However, similar to wetland and stream banking, more and more project proponents are now opting to purchase species conservation credits because it allows them to get project approvals faster, releases them from liability of ensuring that the conservation is successful, and is often more cost efficient.

As further described below, species conservation credits can be created on private or public lands by conserving species habitat and obtaining regulatory approval to create credits. Those credits can be used by project proponents within a pre-approved region called a service area to offset the impacts of their proposed project. There are more than 130 species banks that have been approved by the USFWS across the U.S. These banks provide credits for more than 70 listed species and have protected over 160,000 acres of habitat.

In addition to species banking in the U.S., a number of foreign countries including England, Germany, France, Columbia, Peru, Brazil and South Africa, have developed or are currently developing biodiversity offset systems – as they are known abroad.

How can a landowner create conservation credits?

Creating species conservation credits is often much easier than creating wetland or stream mitigation credits. Landowners will go through an entitlement process with the USFWS or other regulatory agency that will result in a conservation banking agreement (CBA). Depending on the state, the full process – including environmental studies and negotiations with the agencies – may take as few as 6 months. However, landowners should expect the entire process to take at least 2 to 3 years.

The CBA spells out the obligations of the landowners, how credits are actually created, and can be purchased by credit users. In most cases, creating species conservation credits does not require a large restoration effort. Instead the landowner is expected to implement a management plan that will preserve and enhance the habitat for the target species. Very often, landowners find these management plans to be compatible with their existing use of their property, particularly ranching, hunting and recreation. In some cases, grazing can even be required on the property as part of the long-term management plan. Properties used to create the species conservation credits must be protected in perpetuity by a conservation easement. In addition, the landowner is obligated to set aside some of the credit sale proceeds and establish an endowment, to provide funding for the long-term management of the property.

What are the benefits to the landowner?

A species conservation bank may greatly benefit the landowner, if the bank is successful. In most cases, creating a bank does not require a major disturbance to the continued use of the property. Credit sales can provide a sizable additional income for the landowner that is not tied to commodity prices and therefore provides diversification benefits. The value of species credits can vary from a few thousand dollars to over $200,000, depending on the type of species and the credit market. If the landowner decides to sell the conservation bank, the additional income from the future credit sales will be reflected in the value of the land. The endowment funded through credit sales provides annual income to be used for maintenance of the property and it’s facilities, such as fencing, troughs, and roads, decreasing maintenance costs for generations of future landowners. Finally, the conservation easement placed on the land guarantees that the land will not be developed and in many situations will guarantee that the property will remain in agricultural production in perpetuity.

What are the potential downsides and risks to the landowner?

The downsides for a landowner in developing a species bank are the same as those associated with any agricultural or conservation easement. The land used to generate credits must be protected by an easement that will limit future development opportunities and could impact the sale of the property, should the landowner choose to sell it. Although the management plan for the species bank is usually compatible with agricultural use, it may still conflict with some practices and/or constrain the timing of these practices. For example, the management plan could mandate that the property be grazed or rested in certain time periods.

The risk of species bank failure due to a change in weather patterns or a design flaw is low because species banking does not typically require an intensive land restoration effort. If the target species for the bank were delisted, (i.e. no longer protected by federal or state law) the market for that type of credits would be eliminated. However, the risk of delisting is also considered low because it rarely occurs. Furthermore, delisting entails lengthy agency review processes, as opposed to occurring quickly without any warning.

Finally, there are investment risks if a landowner also invests capital into the development of the species conservation bank. The conservation bank may not be approved by the federal or state agencies, which could result in a loss of the capital invested in the studies and entitlement process. The cost of preparing these documents can range from $200,000 to over $1,000,000. The market may also not materialize as expected leading to slower sales and lower revenues. A landowner interested in investing in a species conservation bank should conduct a market analysis prior to committing to the project.

What about habitat exchanges?

A habitat credit exchange is a new type of compensatory mitigation mechanism that can create new, and potentially significant revenue streams for private landowners. The additional revenue can fund improvements to habitat, the property, as well as to the agricultural operation. Habitat credit exchanges are similar to species banks in that they are designed to provide streamlined habitat mitigation and are largely compatible with agricultural and ranching operations. However, habitat credit exchanges differ in that they provide an overarching framework for multiple landowners to enroll and create species credit projects across a designated region. Additionally, habitat credit exchanges have been developed for non-listed candidate species, whereas species banks are for state or federally protected species only.

As of today there are at least 6 exchanges open for business or under development. The first known transaction occurred in November 2017 through the Nevada Conservation Credit System, an exchange developed to achieve net conservation gain from Greater Sage-grouse mitigation. The transaction encompassed 30-year credits generated from 9,750 acres of working lands to offset permitted impacts from the expansion of the Bald Mountain Mine. As of today, approximately a dozen landowners are in the process of enrolling in the Nevada Conservation Credit System, and several impact projects are currently in the process of fulfilling their mitigation obligation using the exchange.

Habitat credit exchanges often use sophisticated habitat metrics and performance requirements to assess the quantity and quality of habitat for which credits are awarded. The exchanges are intended to provide streamlined enrollment, administration and transactions so that landowners can provide habitat cost-effectively and development and energy project proponents can fulfill mitigation requirements efficiently.

Although habitat credit exchanges can provide new revenue streams for ranchers and farmers, they may also be required to take on significant financial liability tied to maintaining the quality of the habitat. Understanding market dynamics and crediting potential can require significant technical capabilities and experience, so landowners should consult with restoration, finance and legal professionals with the right expertise prior to enrolling their land in an exchange.

How do I know if my land could qualify for a species bank?

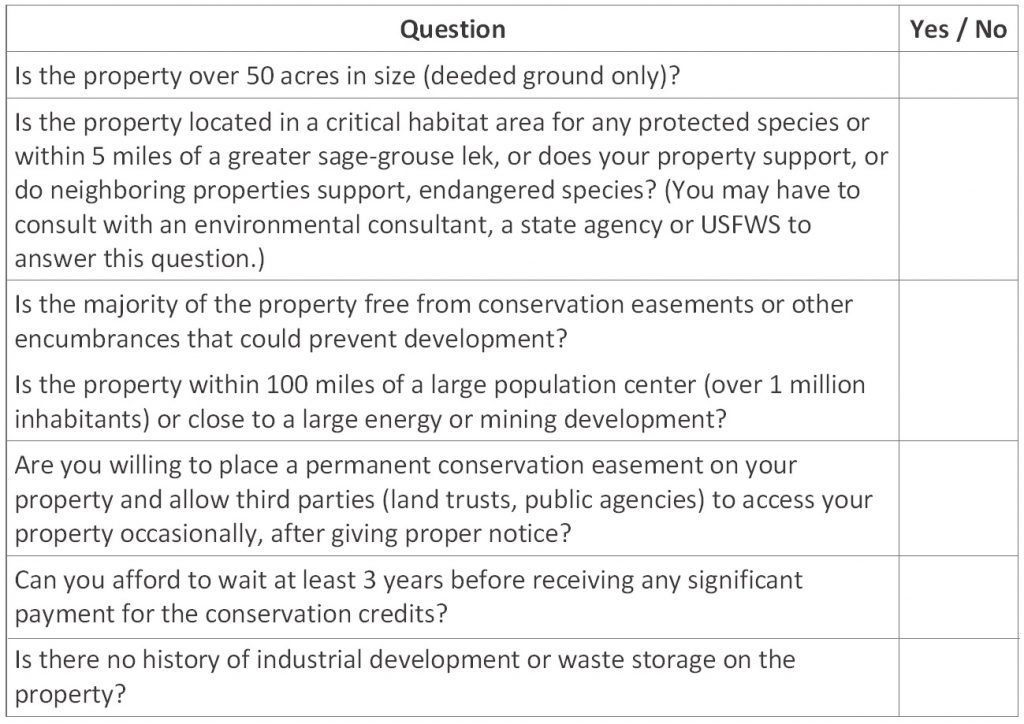

If you are interested in determining whether or not your land could qualify for a species conservation bank, complete the checklist below. If you respond “yes” to all questions, you may be a strong candidate for a conservation bank. If so, we would be happy to answer any questions you have.

Please note that some properties may be eligible for a dual wetland and species bank. If you are interested in learning more about wetland mitigation banking, please see the second blog in this series: Wetland and Stream Mitigation Banking.

WRA, Inc. offers professional consulting services in plant, wildlife, and wetland ecology, water resources engineering, regulatory compliance, mitigation banking, conservation finance, environmental planning, GIS, and landscape architecture. WRA is a national leader in the wetland and species banking industry and recently developed the largest bank in the country. WRA’s conservation finance team is pioneering new monetization approaches across carbon, water, species and ecotourism markets.