Conservation Easements

Conservation Finance Series—Part Four of Eight

By Jane Rice and Ben Guillon, WRA, Inc., in collaboration with Erik Glenn, Executive Director of Colorado Cattlemen’s Agricultural Land Trust.

How do conservation easements work?

A conservation easement is a voluntary commitment by a landowner to limit development on his/her property and protect resources like wildlife habitat, open spaces, agriculture, historic landmarks and scenic vistas. The easement is tailored to the unique conservation values of the property and can be designed to encourage the continuation of farming and ranching activities or recreational uses like hunting and fishing. The legal agreement is made between the landowner and a qualified organization that will act as the easement holder. This organization is typically a land trust, which the landowner may select. Conservation easements are permanent and remain in place regardless of changes in land ownership.

How can a landowner put a conservation easement on their property?

A landowner who is interested in putting a conservation easement on his/her property should contact his/her local or regional land trust to request information about the easement application process and associated costs. The land trust will evaluate whether or not the property meets their organization’s selection criteria based on the application submitted by the landowner and a site visit. If the property is selected for an easement, the terms of the agreement will be negotiated between the land trust and the landowner and in some instances third party funders. The landowner is advised to consult legal counsel when negotiating a conservation easement. Before the conservation easement can be conveyed, the following due diligence reports must be completed: title, conservation easement appraisal, mineral remoteness assessment and baseline inventory report. In most cases, the landowner is responsible for hiring and paying professionals to complete these reports. Finally, the closing of the conservation easement is managed by a title company and is recorded in county records.

What is the difference between a donated and purchased conservation easement?

In most cases, a landowner donates the full-appraised value of the conservation easement to the land trust (i.e., a donated conservation easement) and in return receives tax benefits, as described below. If funding is available and the property is a high priority for conservation, the land trust will sometimes pay for a portion or all of the foregone development rights (i.e. a purchased conservation easement). When the land trust pays for a portion of the development rights this is referred to as a “bargain sale.” Overall, purchased conservation easements are less common than donated conservation easements.

What are the benefits to the landowner?

Conservation easements play a critical role in preserving agriculture and ranching in rural communities and avoiding conversion of these lands to development. Donated easements may be treated as a charitable gift, in which case the landowner receives a federal tax deduction. Easements also often result in the reduction of estate taxes. These tax benefits can relieve financial pressures and make it easier for families to maintain working lands amid development pressures. Some landowners who receive tax benefits associated with conservation easements are better positioned to save for retirement, education or healthcare. Sixteen[1] states also offer conservation easement tax credits that can be used by the landowner to offset their tax bill. In some cases, these tax credits can be sold to other taxpayers who can benefit from a tax deduction if the landowner would prefer cash to tax deductions. Finally, as mentioned above, in some cases the easement is purchased by the land trust with grant funding, in which case the landowner receives a cash payment.

What does it cost to complete a conservation easement?

Costs vary by state and region and are based on the property and complexity of the easement, but typically range between $70,000 and $150,000. The landowner is responsible for paying these costs. There may be opportunities to work with a land trust to apply for grants to reduce or pay for the transaction costs of the conservation easement.

How long does it take to convey a conservation easement?

The conveyance of a conservation easement typically takes between 9 and 18 months, but can take up to 3 to 5 years in the case of purchased easements if there is a need to raise funds.

What are the requirements for maintaining a conservation easement on the property?

Specific management requirements are not always a part of a conservation easement. If specific management requirements are a part of the easement transaction they will be spelled out either in the conservation easement or an associated management plan. Management requirements vary from land trust to land trust and are often an element of grant funding. All easements will require that the landowner allow for periodic monitoring of the property by the land trust. These site visits are coordinated with the landowner in advance and the landowner typically accompanies that land trust staff on site. The land trust has the right to enforce restrictions on the use of the land in accordance with the easement terms.

What are the potential downsides and risks to the landowner?

When a conservation easement is put on a property, the property loses development rights and the land is devalued accordingly. Typically, a conservation easement will reduce the value of the property by 35% to 65% depending on the location and type of property and the deed restrictions. A landowner may still sell the property; however, the financial opportunity of a potential future sale is reduced. As further described below, once a conservation easement is in place, the property may no longer be eligible for a wetland or species bank, or other land monetization opportunity. Given these constraints and risks, a conservation easement is most appropriate for a landowner who wishes to maintain the agricultural heritage and conservation values of the land, as opposed to converting the land to another use or selling the land for conversion. Furthermore, a conservation easement is suitable for a landowner who does not want to invest in a potentially more complicated and costly land monetization option, like a wetland mitigation bank. That said, negotiating the conservation easement deed can also be complex and time consuming. Finally, an additional risk is that the regulatory authorities (such as IRS for federal tax deductions) may not approve of the conservation easement as a charitable donation. This may be the case, for example, if the landowner is already obligated to give an easement on his/her property as part of a transaction or of a permitting process. In this case, the landowner would earn no tax benefits from the easement and the land would remain encumbered in perpetuity. It should also be noted that the easement cannot be reversed once it is conveyed.

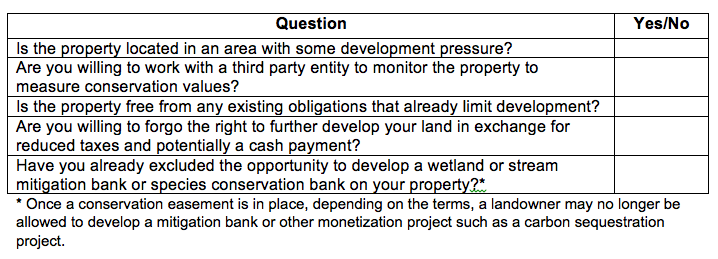

How do I decide whether to a put a conservation easement on my property?

Ultimately, a conservation easement will need to be approved by the land trust based on their priorities and selection criteria. However, there are several screening questions that a landowner can answer to decide whether or not to apply for a conservation easement. If you answer “yes” to all of these questions, you may be a strong candidate for a conservation easement and should reach out to your local or regional land trust for more information.

[1] http://www.conservationeasementadvisors.com/overview/state.php

WRA, Inc. offers professional consulting services in plant, wildlife, and wetland ecology, water resources engineering, regulatory compliance, mitigation banking, conservation finance, environmental planning, GIS, and landscape architecture. WRA is a national leader in the wetland and species banking industry and recently developed the largest bank in the country. WRA’s conservation finance team is pioneering new monetization approaches across carbon, water, species and ecotourism markets.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Publishing this content does not constitute an endorsement by the Western Landowners Alliance or any employee thereof either of the specific content itself or of other opinions or affiliations that the author(s) may have.*

Photo: William C. Gladish