Closure of USGS Water Science Centers Could Harm Western Producers

The closure of 25 United States Geological Survey Water Science Centers will have outsize impacts on rural western communities that rely on accurate information about water, flooding and drought conditions.

Earlier this month, the Trump administration moved to shutter USGS facilities as part of their cost-cutting maneuvers. The decision to close 25 water science centers appears to have been made based solely on the termination dates of their building leases. Six of the 25 centers are located in Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, Washington and Wyoming, and are responsible for water information in eight western states.

According to a USGS employee who spoke to On Land with the condition of anonymity, these closures will have big impacts on the quality of water information and the accuracy of emergency preparedness.

“There’s a lot of intricacy and complexity with what we do,” the USGS official said, and closures like these make the job more difficult.

The USGS works with landowners, non-governmental organizations and other partners to monitor, assess, research and provide information to water users about streamflow, groundwater, water quality and water use and availability across the United States. The USGS is the largest provider of in situ water information in the world, including streamflow and salinity monitoring. It has spent the last several years updating the technology to supply real-time data and seasonal predictions of water availability across the United States.

These data streams are particularly important for western water users who rely on accurate water information to make fundamental decisions about their land.

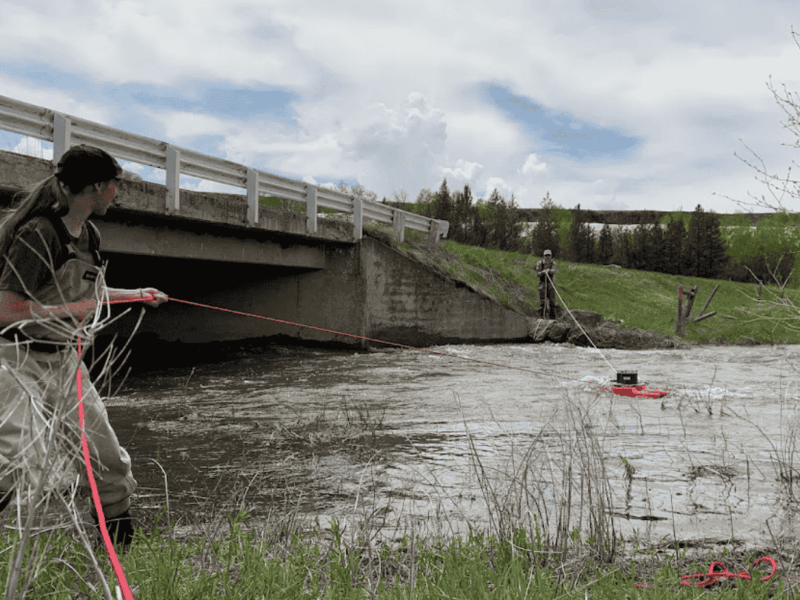

The closure of field offices like the one in Moab, Utah, will particularly complicate stream gage maintenance, which On Land has covered previously. Instead of responding quickly to a sudden change brought about by a flood or other rapidly-moving event, technicians will now have to drive the three and a half hours from Salt Lake City to get to Moab before heading out into the remote areas where stream gages take their measurements. That change will harm flood preparedness in the city of Moab.

“The gages upstream of town are a really big deal during the monsoon season. They can give warnings and valuable time if a big slug of water comes down that could threaten the town,” the USGS official said. The gage measurements can provide up to 30 minutes of warning for local emergency services and residents, a particularly salient piece of information considering the town has flooded multiple times in the past few years. The USGS recently installed a new gage on the North Fork of Mill Creek to help predict those floods, and if it or another key gage goes down, that could spell trouble. With longer travel times to reach those more remote measuring stations, it could take days to get the instrument back up and running. And in that time, another flood could strike Moab and producers without adequate warning.

“In addition to providing critical warnings for weather related emergencies like flooding and drought, stream gage data is vital for agricultural water users to administer irrigation water,” said Morgan Wagoner, Western Water program director for Western Landowners Alliance.

These concerns are very real for folks like Pedro Marques, the executive director of the Big Hole Watershed Committee. The Big Hole River is the most gaged stream in Montana, and supports agricultural producers, ranchers and a booming recreation industry reliant on accurate data to determine best uses for the water in the system. The Big Hole Watershed Committee, established in 1995, is a poster child for collective community action to share the burden of sometimes difficult conservation decisions.

“One of the great successes of the Big Hole’s collaborative conservation was to make sure we have accurate real time stream gage monitoring. How can you manage water if you don’t know how much you have?” Marques said.

“One of the great successes of the Big Hole’s collaborative conservation was to make sure we have accurate real time stream gage monitoring. How can you manage water if you don’t know how much you have?” -Pedro Marques

The model of collective sacrifice to make the Big Hole’s water work for all stakeholders requires precise data on the amount of water in the river and temperature of the water. If a stream gage or monitoring device goes down, it could have ripple effects all across the Big Hole valley. There are not enough bodies to measure every single headgate in the Big Hole, and well-maintained infrastructure makes the system work predictably. Predictability is what producers need to make their life working on the land sustainable, and good data offers that predictability, Marques said. That in turn lets the BHWC make collective, optimal decisions about water use while bringing stakeholders together.

While there has not yet been any sign that the Big Hole gage network is in danger of losing funding, Marques said if the system were to go down, it could lead to a domino effect of negative impacts across the valley.

“If we get down to this model of everybody for themselves, you’re going to end up with senior right holders at the mouth of tributaries with all the power and all the rights,” Marques said. “Even medium size producers will get calls on their water any time we get into a drought situation. That creates a level of unpredictability… And that would make it very difficult for operators to keep working and living on this landscape.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Amanda Konkowski

Thomas,

Do you have a listing of the 25 facilities? I would like to see what facilities may be affected within the Washakie County Conservation District area of the Bighorn Basin in Wyoming. wccd@rtconnect.net

Thomas Plank

Hey Amanda,

Just sent you an email with that information. Let me know if you have any other questions!

Thomas