Keeping Cold Water Cold

Tips for ranch water projects that sustain blue-ribbon trout fisheries

The drive south from the small town of Twin Bridges, Montana, leads through a broad valley to the agricultural hub of Dillon. To the east, the tall peaks of the Ruby Mountains tower against the azure Montana sky. To the west, the snow-dusted ridgeline of the Pioneer Mountain Range casts an indelible impression during the late light of summer. Between these two mountain ranges lies some of the finest ranchland in the state. Cattle and sheep graze on grasses fed by the waters of the Beaverhead River, the essential lifeblood of this valley.

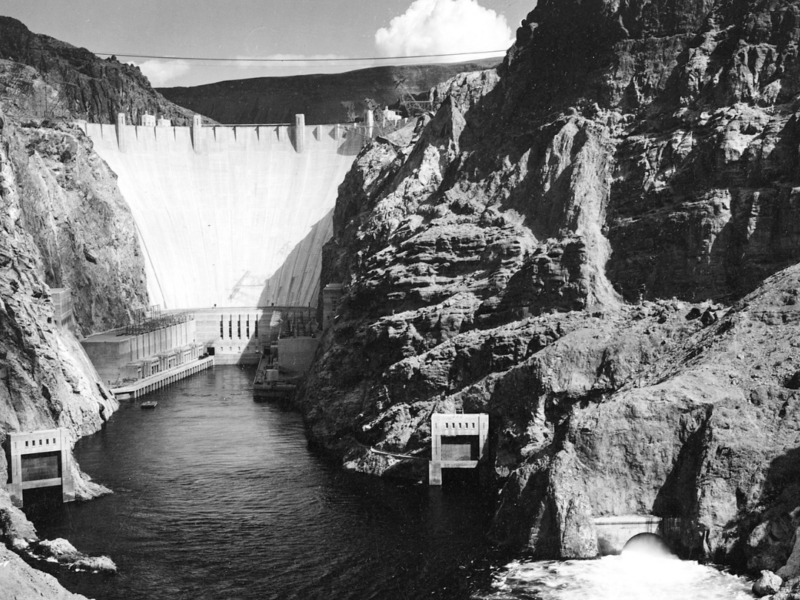

When ranches were established here, landowners drew water from the Beaverhead River to flood irrigate fields for hay and crop production and transform the area into productive farms and ranches. An aerial view of the valley reveals an elaborate web of sloughs and side channels that once meandered alongside the Beaverhead, shifting with the seasons and rerouted frequently by annual flooding events. During the 1900s, irrigation canals were constructed to deliver water to nearby fields. The completion of the Clark Canyon Dam some 20 miles upstream of Dillon in 1964 further regulated the flow of the river.

An unintended consequence of these irrigation systems has become apparent in the ensuing decades. Damming and diverting the river has reduced overall flows and eliminated flooding events, allowing sediment to build up and increasing water temperatures. One of Montana’s blue-ribbon trout fisheries has experienced hard times in recent years as a result. An oft-overlooked component of the problem is how the water that’s diverted for landowner use returns to the river. When agricultural water that warms in the hot summer sun in shallow ditches or surface furrows flows back into the river, it can raise water temperatures. Trout are adapted to the cold, clear water of snowmelt-fed rivers, so river temperatures just a few degrees higher than normal stress the fish and have led to regular angling restrictions during the summer months. But now some landowners are making efforts to right the course of the Beaverhead.

For example, a ranch owner in the valley teamed up with Confluence Consulting Inc., a Bozeman-based team of environmental experts and passionate outdoorspeople, on a project involving the reengineering of a large drainage ditch and an irrigation canal. The goal was to effectively separate surface water and groundwater flows to develop a spring creek fishery on the property. The project developed wetland habitat and a vibrant spring creek that serves as a thermal refuge and important spawning tributary for trout, while isolating the canal and its warmer flows for continued irrigation needs.

“The challenges facing Montana’s trout streams—climate change, loss of habitat, increased angling pressure, to name a few—are all longer-term problems,” said Jim Lovell, president of Confluence Consulting. “Projects like these play a pivotal role in mitigating these challenges and safeguarding Montana’s trout streams.”

Landowners with similar irrigation canals can make modifications to their systems to support healthy river systems and trout habitat. A few changes can have a big impact.

How to tips for landowners

Keep cold water cold: Evaluate the irrigation and drainage plumbing of the property for opportunities to keep cold groundwater from mixing with warm surface water. Relocate existing irrigation infrastructure to isolate groundwater in the proposed channel away from warm, turbid surface irrigation water.

If they exist, refurbish existing drain tiles to improve water quality in the system by using warm, turbid irrigation water to flood irrigate hay, then collect clean groundwater in drain tiles to supply the spring creek.

Place wetland filtration swales strategically to remove sediment and reduce nutrients from irrigation water runoff.

Consider creating deep ponds to reduce water temperatures. By routing the water cleaned in the wetland swales into one or more deep ponds, irrigation water can be cooled before it is discharged back into a trout stream. The pond should be at least 16 feet deep and be constructed to have a deep water outlet. The pond will stratify into temperature zones and will discharge only the coolest water.

Construct a new channel sized appropriately to provide high- quality trout habitat, to convey variable design discharges, meet hydraulic design criteria for trout spawning and transport sediment through the system.

Plant riparian shrubs and trees in strategic locations to provide shade during the summer months to help keep the water cool for as long as possible.

Rich McEldowney, Confluence’s senior wetland and riparian ecologist, admits solutions to help Montana’s fisheries will take time and money, but that with the proper guidance, forethought and the cooperation of many different stakeholders, he sees a bright future for the Beaverhead River and the rest of the state’s blue-ribbon trout streams.

“You need a strategic approach to this sort of problem. We need to be passionate and consistent,” points out McEldowney. “Even if it’s just a ditch, it can become a refuge and benefit fish upstream and down. Over time, landowners doing individual actions can collectively have long-term, significant beneficial impacts on a river.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Tony Malmberg

If fisheries are the primary goal, mimicking nature can be more economically efficient and ecologically sustainable, while retaining a wildness to your landscape. Nature’s migrating herds applied disturbance followed by long periods of rest. This natural behavior builds soil, increases plant density, including willows, and heals rivers. A functional water cycle from the ridgetops to the floodplain catches the raindrop and slows the flow to grow more forage, recharge springs, aquifers, and recharge rivers through the hot season. The same cycle of disturbance and recovery will increase streamside vegetation, narrow the channel, and raise the bed elevation.

Landscapes of cool season plants benefit from irrigation in the cool season. However, cool season plants evolved to shut down when the ambient temperature hits 70 degrees. Irrigation water and instream flows are inversely beneficial, as irrigation water provides greater benefit to the stream during the hot season.

Using livestock to mimic nature can provide these benefits. Not meaning to oversimplify, the riparian area grazing can be boiled down to a few simple points:

1) Graze early where you want willow recriutment, to open grass canopy for willow seedlings.

2) When grazing creek banks in the summer, have a zero tolerance for grazing 2nd year wood. This seems to coincide with a 6 inch grass stubble height.

3) Avoid grazing after frost as the sap in the willows makes them a grazers first choice. Wait until all of the leaves have fallen and livestock won’t bother them as long as they have enough to eat.

If you want to read about my learning process, read my book “Green Grass in the Spring- A Cowboys Guide to Saving the World.