Failing to Deliver

Painfully drawn-out claims process adds another scar after New Mexico’s largest-ever fire

Hell. That’s how Max Garcia, a farmer and rancher from Rociada, New Mexico, describes not only the wildfire that swept across his land in 2022 but the three years since—more than 1,000 days that he describes as a fight to get the federal government to live up to its promises to compensate him for his losses.

The Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire, as it would become known, started on April 6, 2022. It was finally extinguished 137 days later.

During that time, the blaze—which started as a prescribed burn by the U.S. Forest Service that blew past containment lines on the gusts of exceedingly high spring winds—scorched more than 341,000 acres and burned down the homes, trees and dreams of thousands of residents.

“It’s a sadness,” Garcia said. “A disaster. Hell.” The federal government accepted blame before the wildfire was extinguished. An 80-page report issued in June 2022 chronicled the missteps that led to the ill-fated decision to proceed with the burn, despite the warnings of local residents, many of whom have family history on the land that dates back more than a century.

“On the day that our cabin burned, the wind was 85 mph,” said Danette Lucero, homeowner, landowner and Sapello Canyon fire chief at the time of the blaze. “Now tell me, who in their right mind is going to light a fire on that day?”

Resilient Rancher: Max Garcia, a farmer and rancher from Rociada, New Mexico, describes the devastating wildfire that swept across his land in 2022 as “hell,” along with the ongoing three-year battle for federal compensation.

The delays have forced families to live in cars or campers without running water, kept farmers from replanting crops or rebuilding infrastructure.

The focus of many residents’ ire is the agency that provided disaster aid while the land was still ablaze, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). A wing of that agency—the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Claims Office—oversees distributing nearly $4 billion ordered by Congress through the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire Assistance Act to fully compensate those who suffered losses.

A separate ruling added noneconomic damages—including physical and mental health bills—to what victims could claim. A section of FEMA’s website details what its representatives say is a work in progress and a partial success story. Roughly 35,000 people live in the affected area. As of April 10, 2025, the Claims Office has paid over $2.18 billion to more than 15,000 individuals and businesses – an average of $140,000 per claim, said Dianne Segura, FEMA external affairs officer.

For those not in the 15,000, the long wait is a new burn. The delays have forced families to live in cars or campers, without running water, kept farmers from replanting crops or rebuilding infrastructure, and delayed work that would have addressed flooding that continues to damage the region. On top of frustration over delays are disputes with FEMA about the actual value of their property and what they say are endless requests for sometimes difficult-to-come-by paperwork to prove their damages.

“They gave us a partial payment, but we can’t buy partial stuff,” said Floyd Trujillo, a homeowner in Gascon. “I tried to get a loan for a well and my credit didn’t pass because my property wasn’t worth it after the fire. I can’t even borrow the money to make a well.”

“They gave us a partial payment, but we can’t buy partial stuff.”

Floyd Trujillo, homeowner in Gascon

The delays have caught the attention of another government agency. The Department of Homeland Security conducted an audit to determine if the FEMA Claims Office had established a “systematic process to ensure that all payments are made in accordance with the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire Assistance Act.” The audit found it did not.

Joseph Cuffari, inspector general for Homeland Security, issued a memo Feb. 24, 2025, to FEMA acting administrator Cameron Hamilton in which he said the Claims Office “did not always determine compensation amounts within the 180-day timeframe” required by the legislation.

The inspector general also found the Claims Office “did not meet mandatory Congressional reporting requirements,” which left FEMA at risk of “expending appropriated funds without paying all valid claims.” That is a nightmare scenario some residents can’t bear. “I try to just leave it in God’s hands because it’s really very hard,” said Anita Rivera, a total loss claimant from Rociada. “Every day we wake up and it’s still there. We walk outside, it’s still there. The memory will always be there.”

So will the Claims Office—until the very last claim is paid, Segura said. FEMA officials admit to missing the 180-day deadline in some cases but say they are committed to meeting their obligations under the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire Assistance Act.

“We understand that the process can be challenging, and we recognize that for many, the losses remain deeply personal and continue to impact their daily lives,” Segura said. “While no amount of money can undo the damage, the Claims Office remains committed to ensuring every eligible claimant receives the maximum compensation allowable by law.”

Arnold Trujillo contributed to reporting and photography for this story from New Mexico.

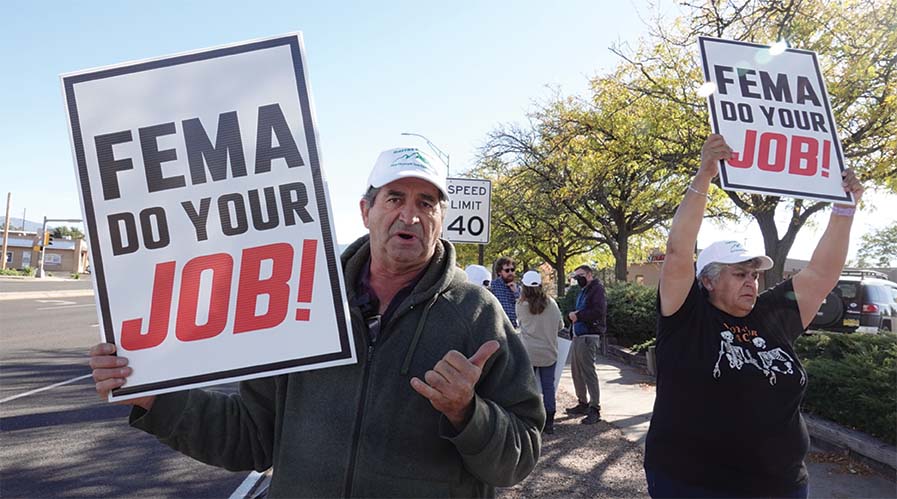

Featured image, top: Luis and Laura Silva, landowners who lost everything in the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fire, speak to a reporter outside of FEMA’s Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Claims Office in Las Vegas, New Mexico during a demonstration in March 2025. FEMA officials admit to missing the 180-day deadline for claim processing in some cases but say they are committed to meeting their obligations under the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire Assistance Act.