To keep both agriculture and healthy rivers out West, we’ll need to get creative.

Cold Mountain Ranch lies majestically at the base of Mount Sopris just outside Carbondale, Colorado, in the heart of the Southern Rocky Mountains. While the mountains of Colorado generally conjure images of roaring streams, bright ponderosa forests and lush riparian meadows, Bill Fales remembers the year the Crystal River went dry. It was 2018, and it was the worst year for both the river and the people of this landscape.

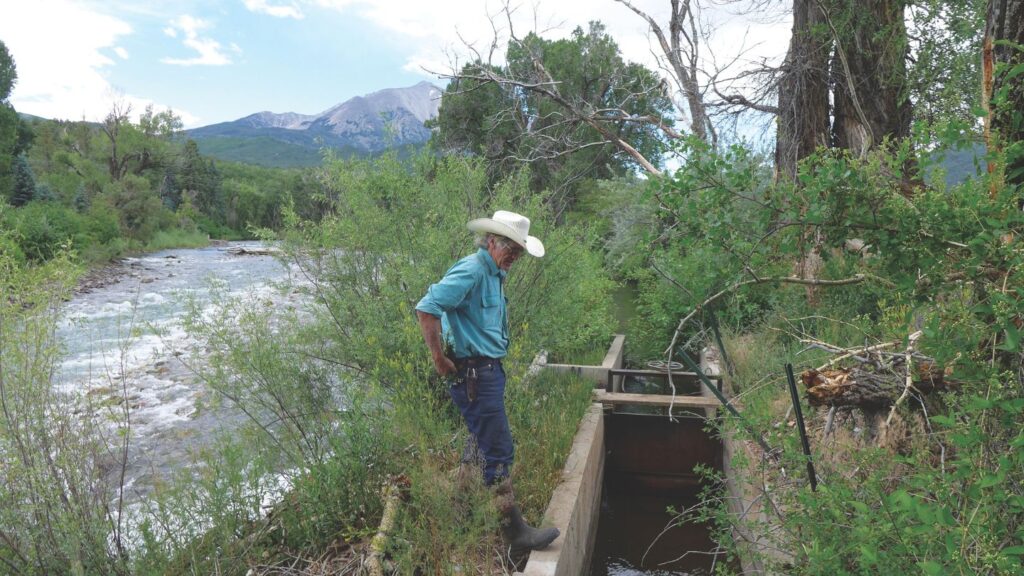

“The residents were unhappy, the irrigators were unhappy, and the fish were really unhappy,” said Fales at a February 2nd webinar hosted by the Western Landowners Alliance. Bill and his wife, Marj Perry, are the owners of Cold Mountain Ranch, a cow-calf operation that irrigates several hundred acres for pasture and hay, which Fales and Perry have placed under agricultural conservation easement, while utilizing grazing permits on nearby public lands. In a typical year, Fales flood irrigates from early May through early October, moving water via ditches around his property in a three-week cycle. Fales gets two cuttings of hay and spring and fall pasture from their land and the agricultural water rights that the easement has forever tied to the property. The property has been in Marj Perry’s family since 1924.

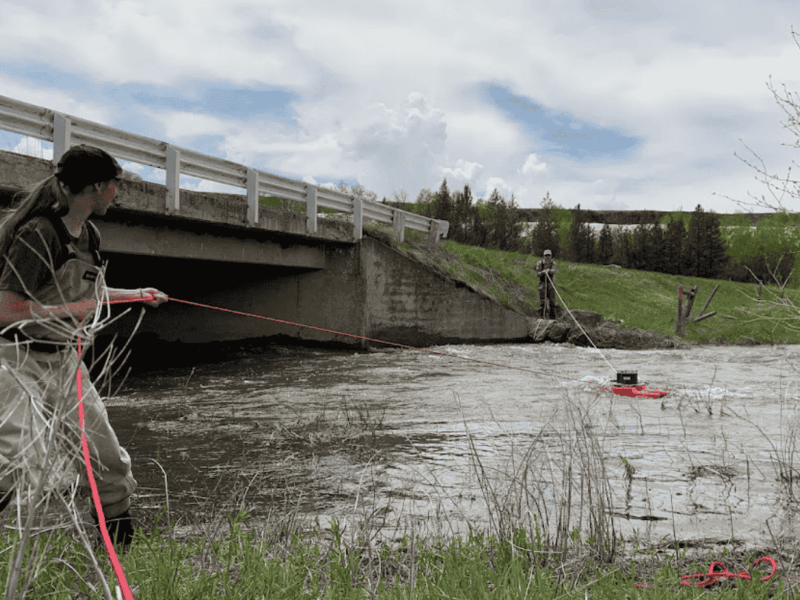

Fales described the “sweep” that was initiated by the first “call” on the Crystal River in history. “When that call was placed on the river in 2018, boy it was like kicking a hornet’s nest. Boy did everyone get excited.” A call on the river is exercised by a senior water right holder, requiring junior water right holders to allow water to pass to the senior right holder. The division engineer then sweeps the river to verify the conditions on the ground and determine how to enforce the doctrine of prior appropriation – the legal tenet that establishes seniority on a body of water in the West. The drought of 2018 forced the community into dialogue, and after many meetings, scientific studies, creative thinking and key legal support via a little-known safe harbor bill passed in the state legislature five years prior, a solution to keep the river from running dry again emerged.

When that call was placed on the river in 2018, boy it was like kicking a hornet’s nest. Boy did everyone get excited.

Bill Fales, Cold Mountain Ranch

In 2013, the Colorado Legislature passed Senate Bill 13-19, allowing water users to temporarily reduce their water use without jeopardizing their legal rights. Without that protection, a water user who voluntarily chose to donate a portion of their agricultural water right for the benefit of the environment could be considered to be abandoning that right, a rule often referred to as “use it or lose it.”

Using the safe harbor provision approved by the State of Colorado, Fales and Perry entered into an agreement with the Colorado Water Trust to voluntarily, and for compensation, to reduce diversions from the Helms Ditch when the Crystal River needs it most. Instead of reducing their total annual water use, as with most agriculture conservation programs, Fales can shift the timing of his diversions to align with the Crystal River’s needs, allowing him to continue producing at least some forage for his animals. Furthermore, the water that remains in the Crystal River is protected from abandonment because it is enrolled in an approved conservation program, in this case with the Colorado Water Trust.

Fales and Perry eventually signed a revised agreement that allowed them to make the decision about whether to close the Helms Ditch headgate once they had their first cutting of hay and based on the moisture received that summer and conditions heading into the fall.

But this temporary, voluntary, and compensated water diversion agreement took some negotiation, according to Fales. A first draft of the diversion agreement required the ranch to shut down the Helms Ditch in late summer without knowing in advance if it would be a good year or a bad year. After some back and forth, Fales and Perry eventually signed a revised agreement that allowed them to make the decision about whether to close the Helms Ditch headgate once they had their first cutting of hay and based on the moisture received that summer and conditions heading into the fall. “The Water Trust was great to work with and they were really responsive to our concerns,” said Fales.

So far, the agreement has only been instituted one time, in 2022. In 2020, there was enough water in the Crystal River to meet the needs of the river, agricultural irrigators, and the community. In 2021, drought conditions across the West were so bad that the ranch decided to keep the water to grow hay to maintain their cow herd as hay prices skyrocketed.

In 2022, however, with the river running low, conditions were right for the agreement to kick in. “Our bank accounts were lower than normal and stockyards were fuller than normal,” said Fales, “So we shut the headgate off and turned the water back through the spillway to the river.”

Based on the terms of the six-year agreement with the Colorado Water Trust, the ranch can be paid for each cubic foot per second (cfs) up to 6 cfs for a total of 20 days per year, for up to five of the six years. The 100 potential days in the agreement therefore has the maximum potential to provide $150,000 in compensation to the ranch. Cold Mountain Ranch was also paid a $5,000 signing bonus for entering the updated agreement as an acknowledgment of their time and effort.

Fales and Perry hoped that more irrigators would get involved to build the collective impact to the river and to their wallets. “We were hoping that once we showed that signing the back of a check is a lot more fun than signing the front of the check, more people would get involved,” said Fales. But so far, few other ranchers in the area have negotiated similar agreements. Fales admits that because the ranch had already tied their water to the land through their conservation easement, in addition to state law SB 13-19, they had more confidence than most that they were not putting their water or operation at risk.

For the Crystal River, water from Cold Mountain Ranch and the Helms ditch is just a start. The Crystal River Management Plan, from 2016, cites a need for 25 cfs during severe drought to meet goals for maintaining the ecosystem. Since the agreement between the Colorado Water Trust and Cold Mountain Ranch contributes a maximum of 6 cfs for just 20 days of the year, additional participation is needed to reach this goal and build the river’s resilience in the face of climate change.

We were hoping that once we showed that signing the back of a check is a lot more fun than signing the front of the check, more people would get involved.

Bill Fales, Cold Mountain Ranch

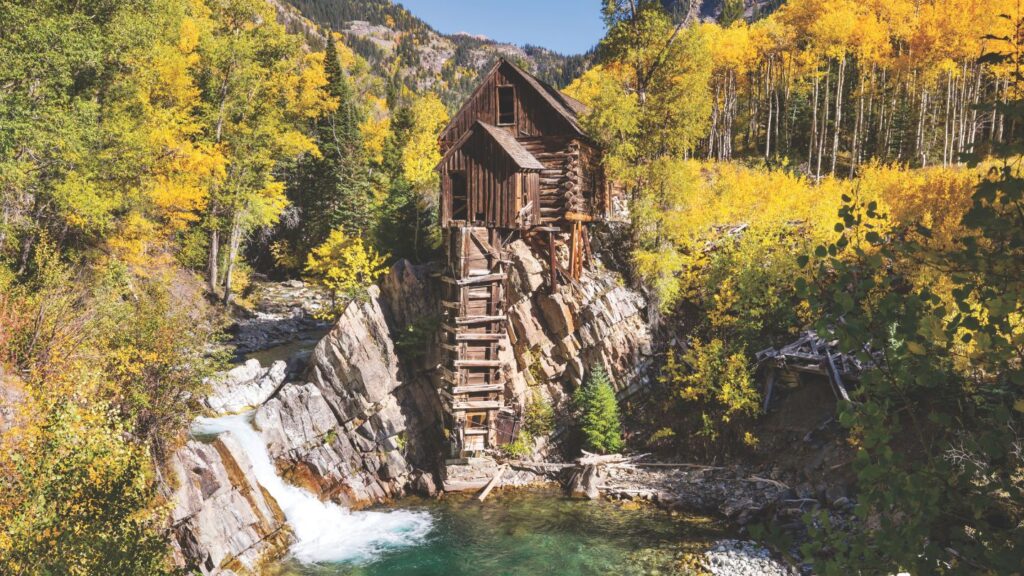

Fales and Perry’s contribution to the Crystal River is significant, though. The Crystal River has its headwaters in the Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness, but as the river descends through the wide pastures above the Town of Carbondale, more than 30 agricultural diversions, representing around 300 cubic feet per second (cfs) of water rights, pull water from the Crystal and its tributaries to irrigate around 4,800 acres of land. In drought years, which are becoming more frequent, sections of the Crystal River run dry. These “impaired”sections occur after major ditches divert water from the river and before their return flows rejoin the Crystal downstream. This change to the river’s hydrology can impact water temperature, habitat quality and habitat availability, diminishing the ecosystem.

The stretch of river that runs through Cold Mountain Ranch is one of the most impaired reaches in the system. “If the water stays in the river for as little as a mile or two, it can make a big difference,” said Heather Tattersall Lewin, director of science and policy at the Roaring Fork Conservancy. “As little as 6 cfs can make a difference in temperature, resiliency, the existence of a cool pool versus a shallow riffle, or the ability for a fish to move from pool to pool or not.”