We asked landowners about water

New research highlights agricultural water users’ preferences for addressing water shortages in the Colorado River Basin

Forty million people in the West rely on water from the Colorado River Basin for their everyday needs. Only about 500,000 of those people live in the household of a farmer or rancher.

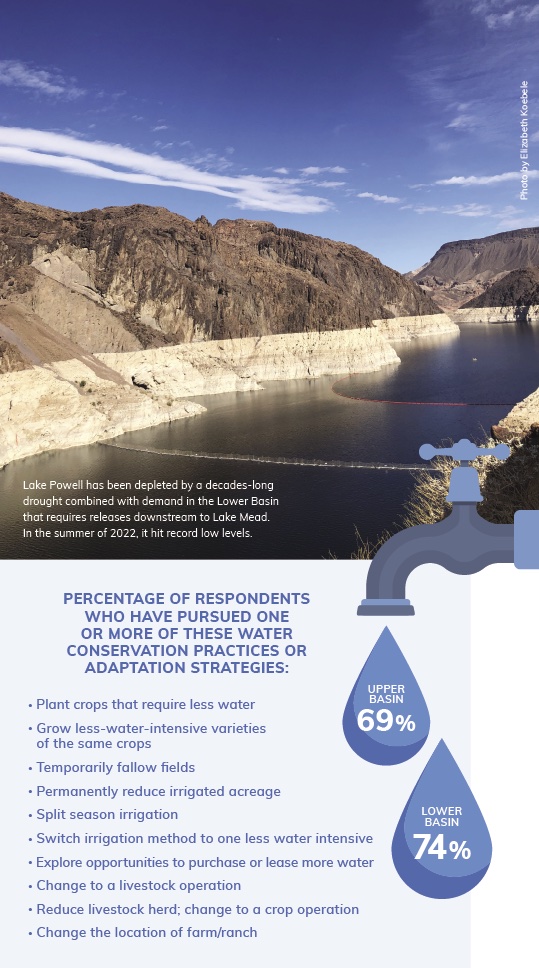

Declining flows in the Colorado River Basin over the last century have increased pressure on water users throughout the Basin and created significant challenges for meeting multiple competing demands. Prolonged drought, increased demand and climate change have led to diminishing water levels in key reservoirs like Lake Mead and Lake Powell, threatening water supply for millions. There is no longer enough water for all of those who depend on it. And yet, it remains true that approximately 80% of the water in the basin is used in agriculture. So, understandably, policy makers, reporters and the public are looking at agriculture for solutions to the West’s water crisis.

Western Landowners Alliance wanted to know: What kinds of questions should they be asking? What kind of answers are they likely to get? What are agricultural water users already thinking, and doing, to be part of solutions? So, we teamed up with the University of Wyoming to ask. We asked more than 6,000 agricultural water users in the Colorado River Basin what they thought about the current situation, their use of and interest in conservation practices, and their preferences for strategies to address water shortages going forward. More than 1,000 of them responded.

The data they provided illuminates at least the first few steps on a path to better communication, more trust, more participation and, ultimately, a more vibrant water future in the West. As Drew Bennett, professor of private land stewardship at the University of Wyoming, put it, “Our hope is that this study can contribute to proactive engagement with the agricultural sector and help chart a path forward for managing chronic water shortages in the Basin.”

What water users are already doing to save

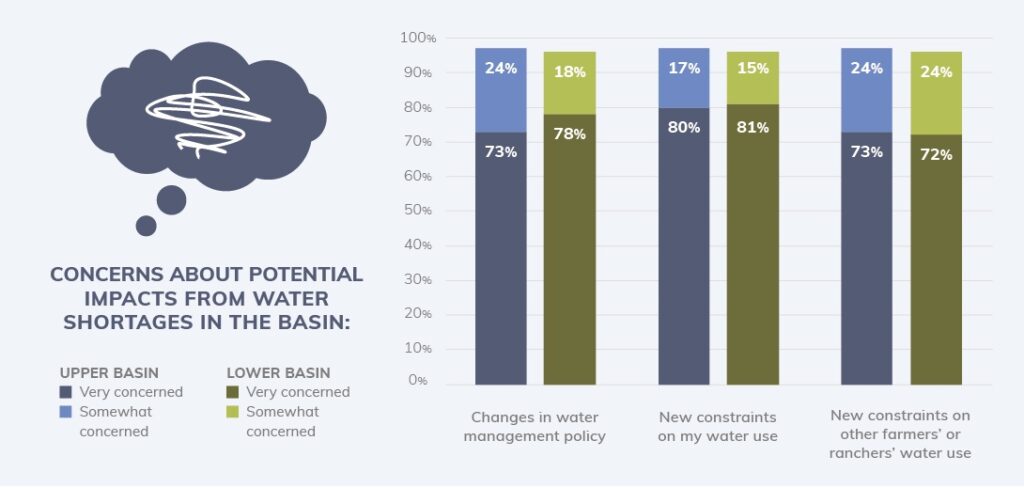

Agricultural water users are primarily concerned with potential water policy changes and water use constraints—particularly for themselves and other farmers and ranchers. In some parts of the Basin, such as along the Central Arizona Project, farmers have already experienced significant cuts to their water deliveries. In other parts, producers are bracing for changes in water management that may accompany the projected increases in drought and streamflow variability.

This concern has led to action. Agricultural water users are already responding to water shortages. Roughly 70% of respondents said they have already adopted one or more water conservation practices or adaptation strategies. And importantly, many would consider adopting additional practices, suggesting hope for voluntary water conservation efforts. We see a willingness among producers to experiment with new approaches to water management on their properties and act as partners in managing water under shortage conditions.

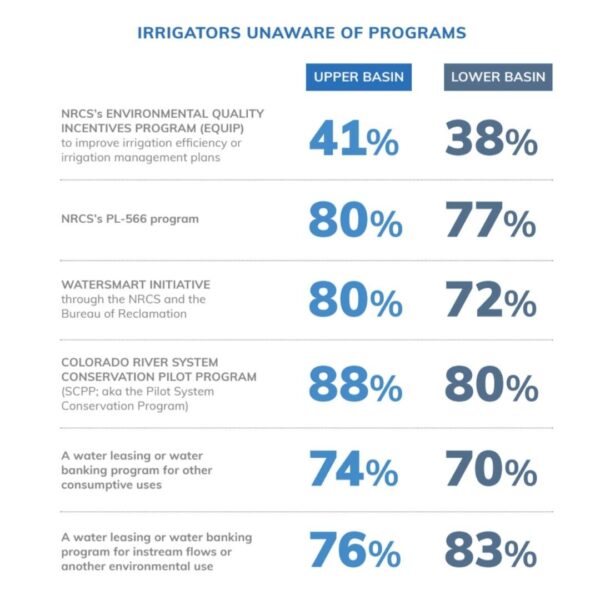

Despite this, very few respondents were aware of formal programs to support water conservation. This lack of knowledge is particularly alarming given the increase in federal funding available for water conservation and the critical role that Western landowners play in managing water resources within their communities.

Providing solutions in the wrong places

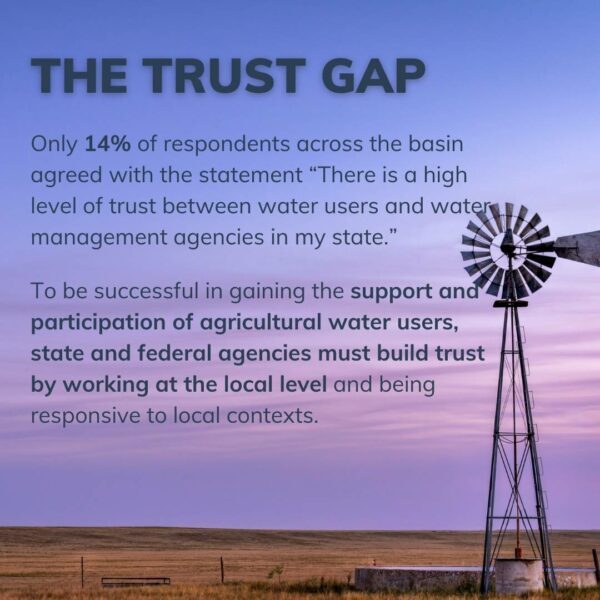

Our study highlights an overwhelming preference for local approaches to managing water shortages and a trust gap with nonlocal agencies. Seventy-four percent of respondents would prefer partnering with a local agency on any water sharing program, for instance. So, while recent federal legislation provides unprecedented resources to address water shortages, increasing funding availability alone is unlikely to sufficiently address the array of challenges across a basin spanning parts of seven states and almost 150,000 square miles, particularly given agricultural water users’ perceptions of federal programs and proposed demand management strategies.

Agricultural water users perceive a disconnect between policies at the state and federal level and management at the local level. For example, only 14% of respondents across the Basin agreed with the statement “There is a high level of trust between water users and water management agencies in my state,” and fewer than 13% agreed with the statement, “My state’s planning process is adequate for dealing with water supply issues.” We reason that this trust gap creates a barrier to gaining buy-in for new water management strategies, even if they are supported by significant funding from state and federal agencies. To be successful in gaining the support and participation of agricultural water users, state and federal agencies must build trust by working at the local level and being responsive to local contexts.

Also of note, most survey respondents were unlikely to adopt water conservation practices as part of formal demand management or system conservation programs to address water shortages and were generally opposed to water transfers as a solution to shortages. Only temporary transfers from agricultural water users to other agricultural water users had less than 50% opposition.

Many users are reluctant to take actions or participate in programs that may threaten their water rights. In order for new conservation programs to succeed, this barrier will need to be addressed, particularly with “use it or lose it” being a foundation of western water law. Respondents also expressed concern about inadequate financial compensation and potential negative cascading effects these types of programs might have on agricultural communities, mirroring the issues encountered in regions extensively affected by “buy-and-dry”.

What comes next

In the arid landscapes of the American West, water is a precious resource that sustains both livelihoods and ecosystems. The Colorado River Basin’s fertile lands and water resources feed millions of people in the U.S. and around the world, and generate an estimated $8 billion in direct agricultural income in addition to other indirect and induced economic activity. Within the Colorado River Basin, the agricultural sector is the largest water user, underscoring the pivotal role farmers and ranchers play in both the repercussions of water scarcity and its solutions. Their leadership and engagement will be key to developing effective policy solutions to today’s water crisis.

The existing policy processes, whether focused on urgent conservation or longer-term basin-wide water management strategies, offer a chance to actively involve agricultural water users. This involvement can support the adaptation of operations to lessen the effects of water scarcity and sustain agricultural livelihoods.

Understanding the perspectives and preferences of agricultural water users, as documented in this report, can help guide the development of solutions that work for producers and other users in the Basin.

Hallie Mahowald is chief programs officer for the Western Landowners Alliance and a co-author of the report. Contact her at hallie@westernlandowners.org.