Birds Got no Beef with Burger

By Kelsey Molloy, The Nature Conservancy

I’m not a coffee drinker so getting up in the pre-dawn is painful for me. I hit snooze a couple times when the alarm goes off at 4 am, check the weather on my phone and reluctantly get up. I drive 90 miles or more to get where I’m going. Once I’m there, however, I don’t need a stimulant to keep me awake. Opening the pickup door and stepping out onto native grass, the sun begins to rise amidst the sound of the dawn chorus. I listen to the melodic tinkling of a Baird’s sparrow (my favorite song, and also set as my morning phone alarm); the downward whirl of the Sprague’s pipit (my ring tone); the buzz of the Brewer’s sparrows, the joyful couplets of the McCown’s longspur. The chestnut-collared longspurs are chasing each other in play, or fight.

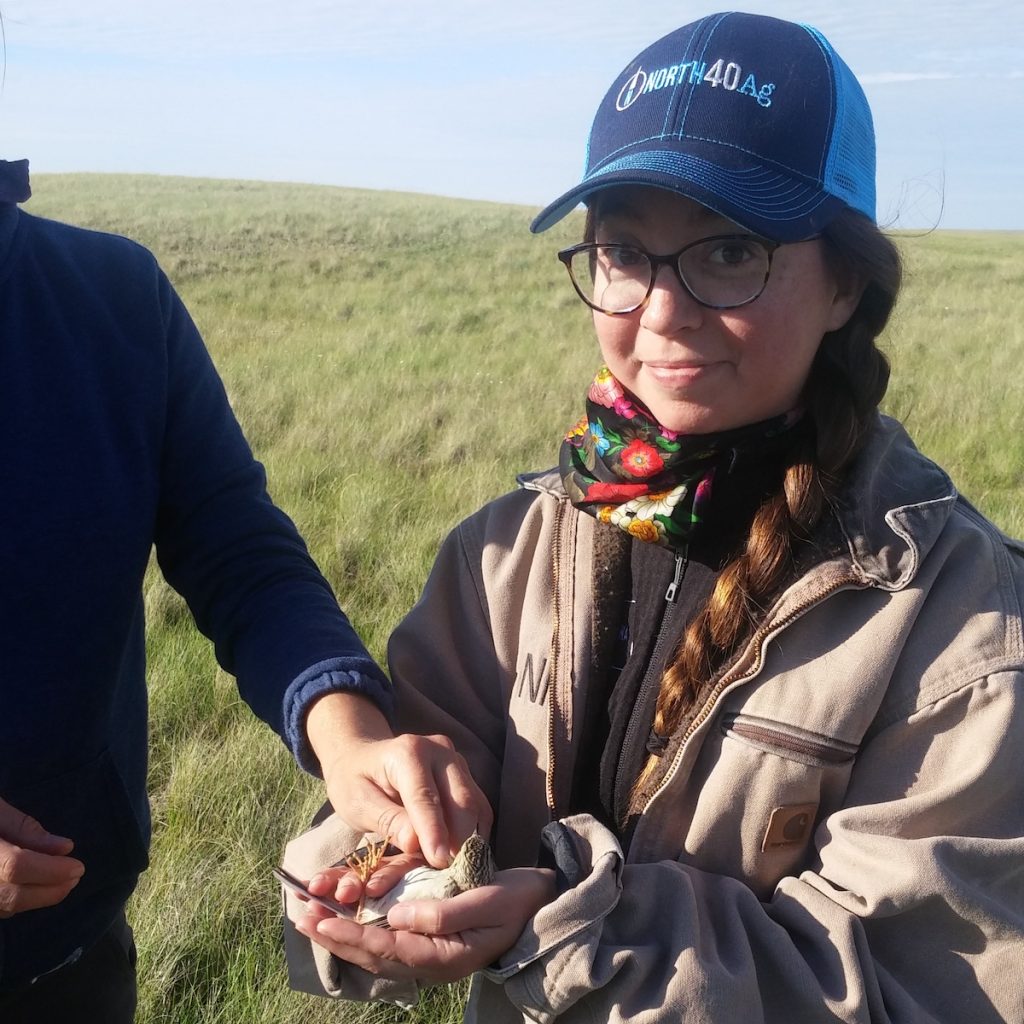

As part of my job as a rangeland ecologist with The Nature Conservancy, I’m on a private ranch (with permission of course) to conduct grassland bird surveys in north-central Montana. For this task, good ears are my most important tool. Most of these birds are small and nondescript (LBBs, Little Brown Birds, in birding jargon) so their songs are used to identify them. But sometimes I’ll see flashy, larger birds like the short-eared owl, a long-billed curlew, or marbled godwit. And, of course, there are always other interesting things to see on the prairie: a fox, a cool mushroom, parasitized plants, fossils, wildflowers. And over all of this is Montana’s dramatic sky, which ranges from golden morning light and striking pink sunrises, to dramatic thunderheads, to bluebird skies with whisps of white clouds.

Adapted to a disappearing prairie home

The grassland birds I monitor are highly adapted to the ever changing conditions found in grassland ecosystems. Over the centuries these birds have made their summer homes from Nebraska all the way up to the Canadian prairies. Each of these birds has a niche to fill. The McCown’s longspurs prefer areas of bare ground and short grass, while others, like the Baird’s sparrows or bobolinks, need moister prairie, and thicker grass. As rain and drought, grasshoppers, fire, and herds of bison once moved across the grasslands, these birds moved to find their ideal habitat each year. Today they still fly south in the fall, some just as far as southern Colorado, Texas and Mexico. Others like the bobolink and Swainson’s hawk fly all the way to Argentina for the winter. Having spent most of the last 10 winters in Montana or Manitoba, I can’t say I blame them!

There was a lot of news coverage in 2019 on threats to bird populations. An article in Science about the loss of close to 3 billion birds in the US highlighted the decline of grassland birds. Overall, there was a 53% decline in grassland birds since 1970, the highest rate of any group of birds.

Some individual species have had it worse than others. During that time Breeding Bird Survey data (from the US Geological Survey) show that Sprague’s pipits have declined by 71% and McCown’s longspur population declined by 87%. Some of these species, like Sprague’s pipit and McCown’s longspur have already ended up on Canada’s version of the Endangered Species list – the Species at Risk Act.

What these birds need most of all are intact grasslands. Even though where I live in Phillips County on Montana’s Hi-line I can see grass in every direction, there are few places on the continent with this much native grassland left. The majority of our grasslands have been plowed up, or developed. Less than 0.1 percent of tallgrass prairies still exist. With grassland habitat loss and fragmentation, many of our native birds are declining across their historic ranges.

Grazing is a land use for the birds

However, these birds do well with cattle grazing. They are adapted to grasslands with grazing disturbance. Research has shown that grazing is just a small component of what influences whether they are in an area or not (soils, moisture, and vegetation being the primary drivers). Since one of northeast Montana’s primary land uses is ranching, these little birds have a chance of persisting.

I’m trying, along with many wonderful partners, to keep these birds from needing protection under the Endangered Species Act. One of the keys to a bright future for grassland birds will be ensuring that sustainable ranching economies and communities persist on the landscape. We’re using tools, such as conservation easements, Candidate Conservation Agreements with Assurances, grassbanking, and on-the-ground grazing projects to help native grasslands, and both the avifaunal and human communities that rely on them, to survive and thrive.

It’s been a surprising path for me to travel from New England to the prairies. Learning about the native grasslands of the Northern Great Plains—first in Saskatchewan and then in Montana—has changed my life. Moving here and learning this ecosystem has forever altered the way I experience the world. Most importantly, it gave me a focused passion. Throughout the process, I’ve met so many people who are forward-thinking, collaborative, and striving toward a shared future for our rural communities and the ecosystems that support them, including all of those LBBs.

About the author

Kelsey Molloy is a rangeland ecologist for The Nature Conservancy in Malta, Montana. She has a degree in Wildlife Biology from the University of Rhode Island. She moved west from the Ocean State in 2011 to attend the University of Manitoba for her graduate work, which brought her to do research in Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan looking at cattle stocking rates and grassland. She has a border collie pup named Buck. She spends all winter reading and waiting for the joy of spring to return. You can follow her wildflower wanderings on Instagram @Kelsey_of_Malta.