Water Rights for Restoration

Conservation Finance Series—Part Seven of Eight

By Jane Rice and Ben Guillon, WRA, Inc., with guest contributor Bill Wombacher of Ryley Carlock & Applewhite.

If you own water rights and are interested in selling or leasing them to restore stream flows and habitat, this article will help you navigate potential opportunities. The article includes an overview of water rights, an explanation of how water rights may be used for instream benefits and considerations for water rights transactions. While much of the information is broadly applicable to landowners in western states, the majority of the examples provided in this article are from our home state of Colorado.

What is a water right?

A water right is essentially a legal entitlement to use water from a body of water and is often tied to real estate ownership. There are two fundamental systems governing water rights law in the United States, one in the East and one in the West. In the eastern U.S., water rights are governed by the riparian doctrine, which basically states that landowners living near a water body have a reasonable right to use that water. A “reasonable right” implies that one landowner’s use of the water does not interfere with other landowners’ ability to use the water. In the western U.S., where water resources are more scarce and there is often a need to divert water away from the source for agriculture, mining and other commercial and residential uses, the prior appropriation doctrine underpins most states’ water law. The prior appropriation doctrine indicates that whoever started using the water first, is first in right to the water. Water rights owners with an older right are considered “senior water rights owners” relative to “junior water rights owners.” In arid or drought stricken locations, not everyone who is entitled to water will actually obtain water. The water regulator may issue calls for water that force junior water rights owners to stop diverting water so that it is available for senior water rights owners.

While states generally follow the applicable regional doctrine, individual states have added their own rules to create unique water law systems. For example, California’s system blends the riparian and prior appropriation approaches. In contrast, Colorado maintains perhaps the purest interpretation of a prior appropriations system. In order to better understand water law in your state, you can usually find public information about water law administration on your state’s Division of Water Resources or State Engineer’s webpage.

How can water rights be used for stream restoration?

In some states landowners can voluntarily sell, lease or donate their water right to improve river or stream flows and enhance habitat. Using water rights for instream benefit is particularly valuable in arid regions or amid drought conditions. However, it is important to structure this type of transaction properly so that the instream use is recognized as a beneficial use under the applicable water law. If not, the water right could be considered vacated and could be lost.

Colorado is one such state that allows for water rights to be used for stream restoration. The Colorado Water Trust is a private organization that works with water rights owners, on a voluntary basis, to restore flows to streams and rivers through water rights sale, lease or alternative transfer methods (ATMs). These agreements typically require approval by the water court and the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB), which is the sole entity that can hold water rights for the purpose of instream flows in the state. Additionally, legislation was recently passed in Colorado that allows large reservoir operators to enter into agreements with the CWCB to structure reservoir releases in a way that benefits the environment, in terms of seasonal timing or flow rates.

Other states are also exploring innovative ways to apply water rights law in a way that benefits the environment and compensates water rights owners for those benefits. Water rights owners who are interested in using their water rights for stream restoration should become well-acquainted with their state’s water laws and consult with a water rights attorney to ensure that they will not be subject to any water law penalties, as described below.

How can a landowner sell or lease his/her water rights?

When a landowner sells (or donates) their water rights for instream flows this is considered a permanent transfer of the water right. The transfer will likely require approval by a state entity (such as the State’s Engineer’s Office) or a water court. A donation of a water right is likely to be tax deductible. A landowner can also lease his/her water right for a specific season over a fixed number of years. A lease is a more flexible mechanism for the landowner than a sale or donation since it is temporary in nature.

Note: The “transfer” of a water right can also refer to a change in the designated use of a water right, as opposed to the sale or lease of a water right.

What can a landowner expect to be paid for water rights?

Water right payments are highly variable and depend on several key factors:

- In the West, the more “senior” the water right, the more money the water rights owner can expect to receive. As described above, seniority refers to how old the water right is relative to other water rights users for the same water body. A more senior water right is more likely to yield the allocated amount and thereby provide a more reliable water supply.

- If the physical yield of the water right is inconsistent, either due to drought or upstream withdrawals, this will reduce the value of the water right.

- A water right will attract a higher price if it is located near municipalities and water districts that are in short supply of water, as dictated by common supply and demand principles. For example, a senior water right near the Front Range of Colorado (where water is in high demand and development is booming) a water right owner could reasonably be paid $10,000 per acre-foot of water.

Some of the most flexible and expensive water rights in the state of Colorado are sold by the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District from the Colorado-Big Thompson (CBT) Project, a federal water diversion project that provides water to the Front Range. The average price of CBT units have neared $30,000 in recent years and parties often look to CBT units to set the price of other water rights. (One unit generates 0.74 acre-feet of water.) For irrigation and municipal water leases in this area, a water rights owner is likely to be paid about $200 per acre-foot per year.

What costs should a landowner expect to incur from selling/leasing a water right?

Water rights transaction costs are also highly variable and depend on the complexity of the situation. In many instances, the only cost would be to retain a water rights attorney to perform due diligence by evaluating the water right and identifying any potential risks or opportunities, which may cost the landowner around $2,000. However, if there is a need to change the water right’s use (as would likely be the case if a water right owner is reducing irrigation in order to increase instream flows) this can be a more complicated and costly process. In a highly contentious situation, costs could easily exceed $100,000 in legal and engineering fees. For this reason, water rights owners should consult with a water rights attorney early on in the process to gauge difficulty, cost and risk associated with the particular situation. An experienced water rights attorney could also likely provide information on recent water transactions in a particular area to give a sense of potential price.

What risks should a landowner be aware of associated with selling/leasing a water right?

As mentioned above, changing a water right use (from irrigation to instream flows, for example) can require the approval of the state water court. Presenting the water right to a water court and requesting a change in use can open up the water right to scrutiny, which could potentially result in a reduced or eliminated water right. For example, the water court may analyze the historical beneficial use of the water and find that it is less than the amount stated in the water rights decree, which could result in a lower allocation for the water rights user going forward. This is referred to as the “use it or lose it” principle. Given this risk, it is again important to evaluate the water right with a water attorney and assess historical beneficial use information before presenting the request to the water court or State Engineer’s office.

If a landowner wants to put his/her water right to beneficial instream use, will he/she have to terminate all irrigation and agricultural activities on the property?

No, using a water right for beneficial instream use does not require a “buy and dry” scenario where the water right is permanently sold and the land can no longer be used for irrigated agriculture. A landowner can use an ATM as described in the Colorado Water Trust example provided below. ATM approaches can be tailored to a landowner’s needs such that the water right is dedicated for instream use for one portion of the year, while the landowner can still use the water for irrigation in other seasons. These arrangements are made for certain years over a multi-year period.

Water Rights Transaction Program Examples

The Colorado Water Trust (CWT)

The CWT uses Colorado’s complex water laws to the advantage of the environment and society, through the restoration of river and stream flows. One example of an innovative CWT project is the McKinley Ditch project, which was the first of its kind split-season water use agreement. In 2014, CWT purchased a portion of the McKinley Ditch to help restore late summer flows to the Little Cimarron River, located in western Colorado. The goals of the project were two-fold: reconnect riparian habitat and keep agricultural fields irrigated. The CWT filed for a change of water right in the Colorado Water Court in order to use the ditch water for instream flows during certain times of the year. Instead of what some call a “buy and dry” agreement, CWT used a split-season approach where the water right was only used for instream flows in the late summer and early fall, while water could be used for irrigation in the spring and early summer, such that the agricultural operations on the land could be maintained. This type of approach is considered an ATM because the water right is not permanently transferred to instream use.

The Columbia Basin Water Transactions Program (CBWTP)

The CBWTP was launched in 2002 in response to chronically diminished stream flows along the Columbia River and the resulting harm to Pacific salmon and steelhead trout. In order to increase stream flows and restore habitat, the CBWTP acquires permanent or temporary water rights from landowners, on a voluntary basis. In this way, water that would be legally withdrawn during the peak growing season is instead left in the streams to provide beneficial habitat. To complete these transactions, CBWTP works with local organizations and landowners along the Columbia River Basin, including in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana. The CBWTP is managed by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and funding is primarily provided by the Bonneville Power Administration.

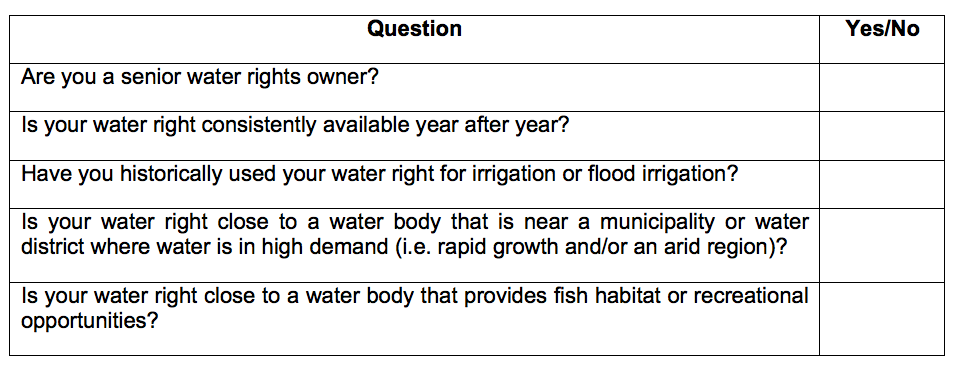

Am I a candidate for water rights sale or lease?

If you answer “yes” to all of these questions, you may be a strong candidate for a water rights sale or lease for instream flow or habitat restoration.

WRA, Inc. offers professional consulting services in plant, wildlife, and wetland ecology, water resources engineering, regulatory compliance, mitigation banking, conservation finance, environmental planning, GIS, and landscape architecture. WRA is a national leader in the wetland and species banking industry and recently developed the largest bank in the country. WRA’s conservation finance team is pioneering new monetization approaches across carbon, water, species and ecotourism markets.

William “Bill” Wombacher, a water rights attorney based in Denver, works with Ryley Carlock & Applewhite’s award-winning Water and Environmental team. His practice focuses on helping clients with complex water rights issues throughout Colorado, including adjudications, litigation, well permitting, and water planning. Ryley Carlock & Applewhite’s water and environmental attorneys provide a full range of experience in water, energy, resources and environmental matters across the Southwest. From banks to golf course developers, high-tech companies to heavy industries, a diverse cross-section of public and private enterprises rely on the firm’s Water, Energy, Resources and Environmental Attorneys for assistance in the areas of water law, environmental regulation, environmental litigation, environmental legislation, natural resource strategies and power-related issues. Bill can be reached at 303.813.6704 and wwombacher@rcalaw.com.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s). Publishing this content does not constitute an endorsement by the Western Landowners Alliance or any employee thereof either of the specific content itself or of other opinions or affiliations that the author(s) may have.*

Photo Credit: Adam Schalau. Piojo Ranch, New Mexico.